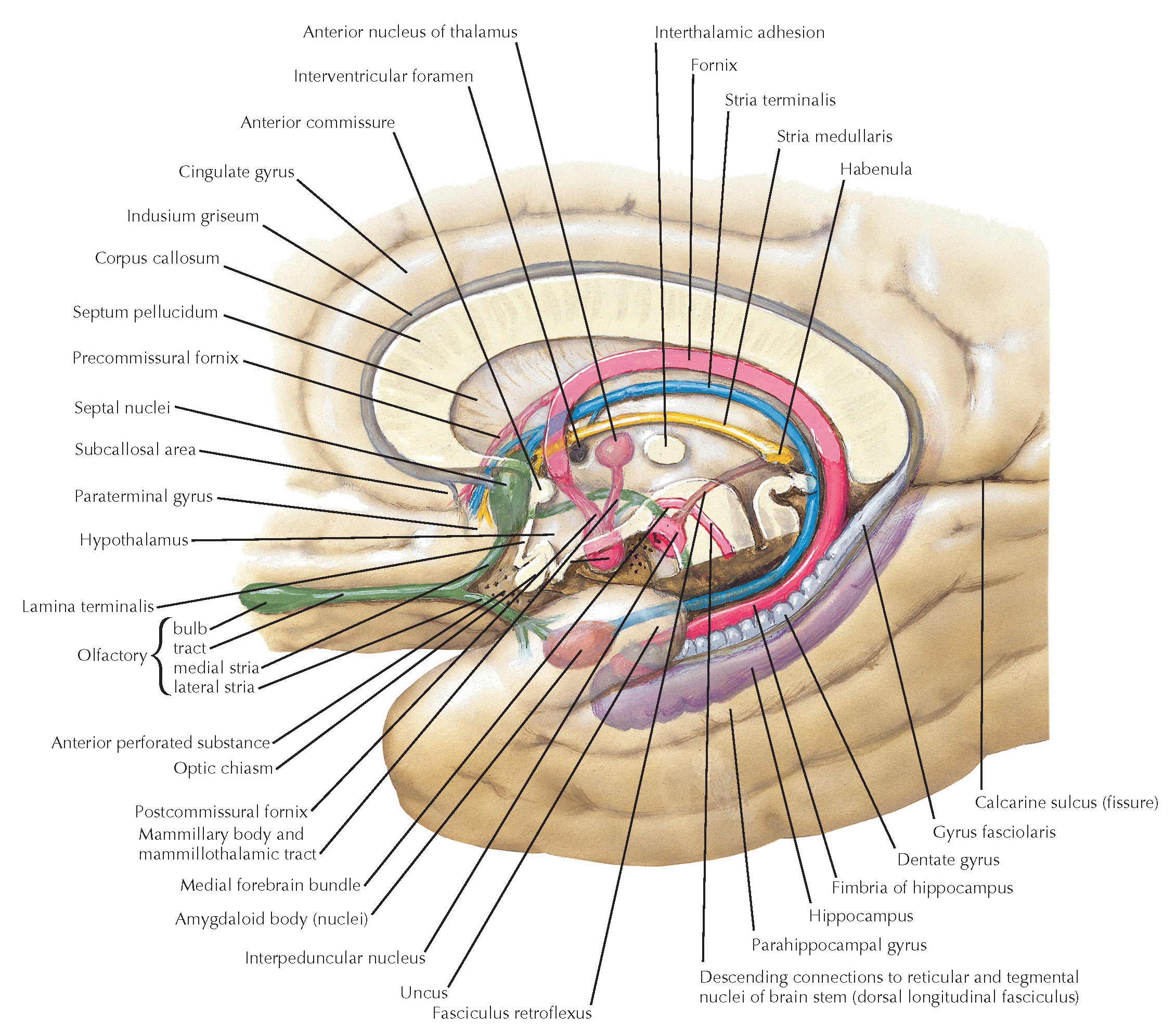

The term limbic is derived from limbus, meaning ring. Many of these structures and their pathways in the limbic system form a ring around the diencephalon. They are involved in emotional behavior and individualized interpretations of external and internal stimuli. The hippocampal formation and its major pathway, the fornix, curve into the anterior pole of the diencephalon, forming precommissural (to the septum) and postcommissural (to the hypothalamus) connections in relation to the anterior commissure. The amygdaloid nuclei give rise to several pathways; one, the stria terminalis, extends in a C-shaped course around the diencephalon into the hypothalamus and basal forebrain. The olfactory tract communicates directly with several limbic forebrain areas; it is the only sensory system to entirely bypass the thalamus and terminate directly in cortical and subcortical zones of the telencephalon. Connections from the septal nuclei to the habenula (stria medullaris thalami) connect the limbic forebrain to the brain stem. The amygdaloid nuclei and hippocampus (shaded) are deep to the cortex.

Clinical Point

Many of the limbic forebrain structures are connected

with the hypothalamus by C-shaped structures, such as the hippocampus and the

fornix, and with the amygdala and the stria terminalis. The amygdala has additional

direct connections into the hypothalamus via the ventral amygdalofugal pathway.

The amygdaloid nuclei receive multi- modal sensory information from cortical regions

and provide context for this input, particularly emotions related to fear responses.

Bilateral amygdaloid damage results in the loss of the fear response and also in

failure to recognize facial responses of fear in others.

The hippocampal formation processes abundant information

from the temporal lobe, subiculum, and entorhinal cortex and sends connections through

the fornix to the hypothalamus and septal nuclei, with subsequent connections through

the thalamus to the cingulate cortex. These structures are part of the so-called

Papez circuit. The hippocampal formation is particularly vulnerable to ischemia;

damage bilaterally results in the inability to consolidate new information into

long-term memory. A common pattern may be observed in older persons who forget who

has talked with them minutes before or forget what they had for breakfast (or even

whether they had breakfast) but can recall details from the past that have some

degree of accuracy.