UPPER AIRWAY

OBSTRUCTION AND THE HEIMLICH MANEUVER

“How many persons have perished, perhaps in an instant, and in the midst of a hearty laugh, the recital of an amusing anecdote, or the utterance of a funny joke, from the interception at the glottis of a piece of meat, a crumb of bread, a morsel of cheese, or a bit of potato, without suspicion on the part of those around of the real nature of the case!”

Although Gross wrote this comment in 1854, more than

100 years passed before Haugen, in 1963, used the term café coronary to

describe sudden death—usually occurring in a restaurant—from food asphyxiation.

Haugen and others advised that airway obstruction should immediately be

suspected whenever an individual suddenly loses consciousness while dining and

that, if death follows, one should question a diagnosis of “coronary” or

“natural” causes.

In 1974, Heimlich first reported the results of animal

studies on a new technique he proposed to relieve a completely obstructed

airway. Over the next 2 years, Heimlich received reports of clinical

experiences with the technique, documenting approximately 500 instances of

successful resuscitative efforts, including 11 cases of self-resuscitation. His

technique is now known as the Heimlich maneuver. Heimlich’s work redirected

attention to this important problem of food choking and foreign-body airway

obstruction, including the need for immediate action.

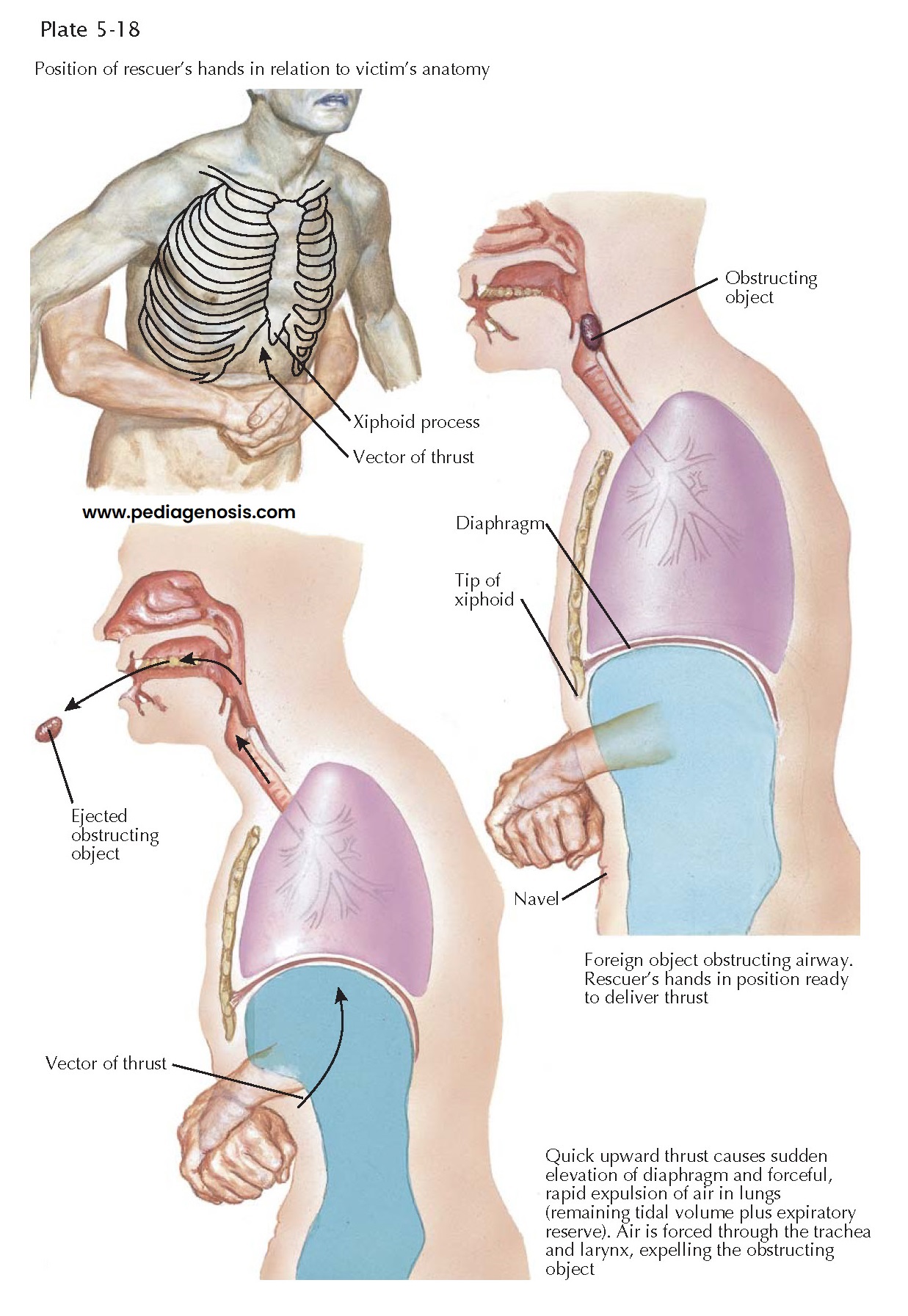

The Heimlich maneuver is a technique whereby sub-

diaphragmatic compression creates an expulsive force from the lungs that is

able to eject an obstructing object from the airway.

The anatomic basis for the Heimlich maneuver was

established by observing that when a patient is in the lateral position during

thoracotomy, pressure applied by the surgeon’s fist upward into the abdomen

below the rib cage causes the diaphragm to rise several inches into the pleural

cavity. After studying airflow rates and pressures in conscious, healthy, adult

volunteers, Heim- lich concluded that the maneuver produced an average airflow

of 205 L/min and pressure of 31 mm Hg, expel- ling an average of 945 mL of air

in approximately 0.25 second. The projectile force thus generated propels

nearly any obstruction from the airway.

Notably, chest thrusts and back slaps should not be

used, as was once advocated. Chest thrusts produce less expelling force than

the Heimlich maneuver, and back slaps may actually force an obstructing object

deeper into the lungs.

To perform the Heimlich maneuver on an adult who is

standing, the rescuer stands directly behind the victim.

1.

The rescuer

puts one arm around the victim’s waist and makes a closed fist, positioning the

thumb side of his or her fist just above the victim’s navel and well below

the tip of the xiphoid process.

2.

The rescuer

encircles the victim’s waist with his or her free arm and clasps his or her closed fist.

3.

The rescuer

gives a single, sharp, quick inward and upward compression or “thrust.”

Sometimes a series of two or more thrusts may be necessary.

The compressions almost invariably cause the food

bolus or foreign body to be ejected completely, or to “pop” out, or else propel

the object into the mouth, where it is easily reached.

The Heimlich maneuver can also be performed in an adult victim who collapses to the floor supine. The rescuer simply kneels astride or straddles the victim and provides the maneuver via sharp inward and upward thrusts of the heel of the hand, maintaining a midline position. Adults may also apply the maneuver to them-selves, either with their own fist, or by thrusting them- selves over the edge of a chair, table, or other object to duplicate a rescuer’s effort. In children, the rescuer applies the same technique using the index and middle fingers of one or both hands, depending on the child’s size, either with the child supine, or held upright in the rescuer’s lap. Infants should never be held upside down, and back blows should not be used.