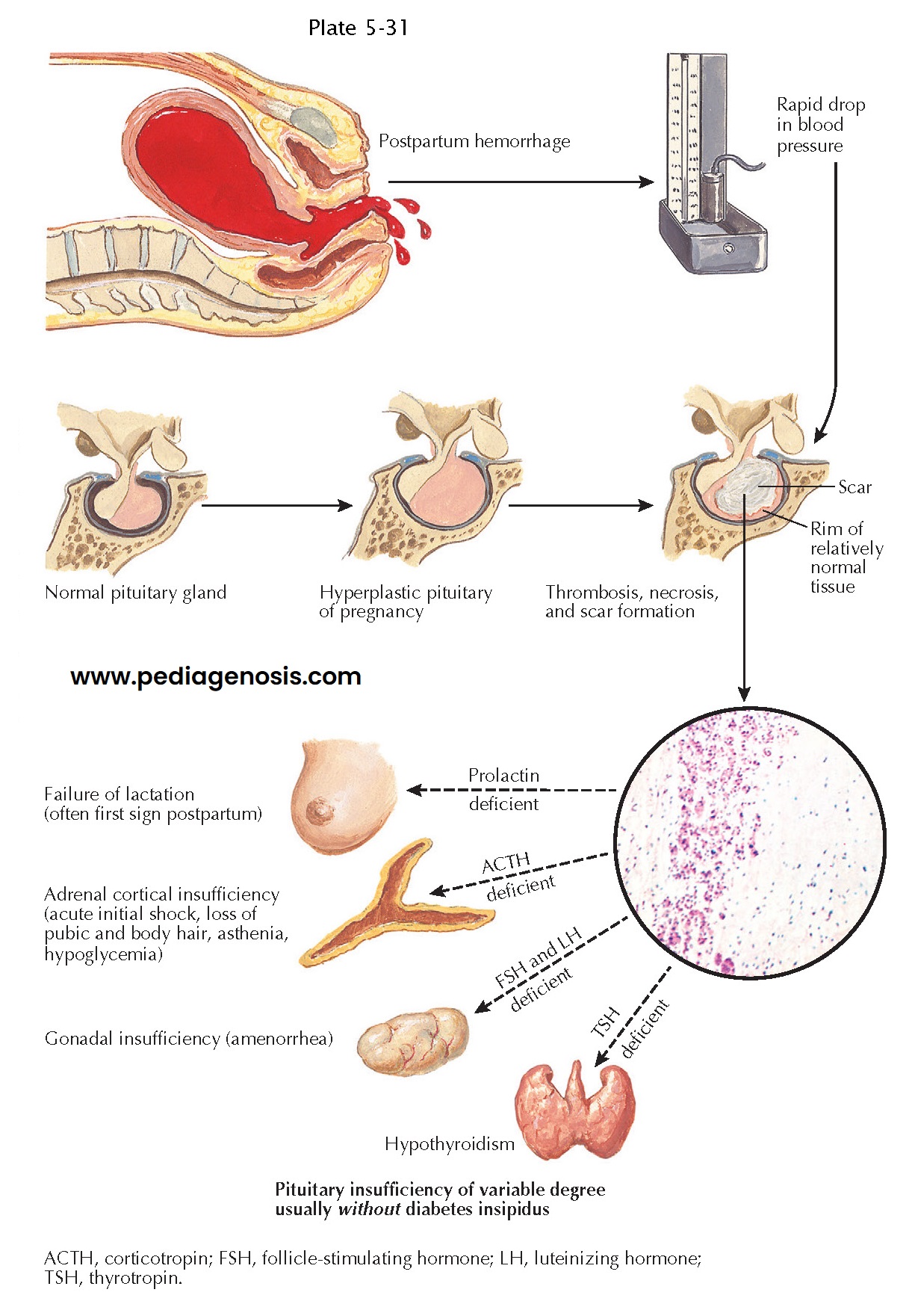

Postpartum Pituitary Infarction (Sheehan Syndrome)

In 1937, Sheehan first

described the development of pituitary infarction in the setting of hemorrhagic

shock occurring after delivery. This entity is much less commonly seen in developed

countries today, likely as a result of modern advances in obstetric care.

To understand the development of postpartum pituitary infarction, one has to consider that the pituitary gland becomes hyperplastic (approximately doubling in mass) during pregnancy as a result of progressive lactotroph hyperplasia occurring until term. Because there is no concurrent increase in blood supply to the pituitary, lactotroph hyperplasia makes the gland more vulnerable to vascular insults during pregnancy and the peripartum period. To highlight the important role of pituitary hyperplasia in the pathogenesis of infarction, it may be noted that pituitary infarction is very rare in nongravid patients in shock. The precise role of vascular spasm, thrombosis, and vascular compression as causative factors in the pathogenesis of Sheehan syndrome is still debated, but the condition ultimately involves infarction of the anterior pituitary lobe as a result of severe decrease in blood flow through the gland.

It may also be

noted that the anterior lobe of the pituitary is more vulnerable to

ischemia than the posterior lobe because the former receives blood supply

through a low-pressure portal system. In contrast, the posterior pituitary

receives direct arterial blood supply through the inferior hypophyseal

arteries. As a consequence, the pars tuberalis and the posterior pituitary lobe

are usually spared in these patients, who generally do not develop central

diabetes insipidus.

Infarction of

the anterior pituitary lobe leads to a gradual decrease in the size of the

pituitary gland, which is partly replaced by fibrous scar tissue. On magnetic

resonance imaging, there is a gradual decrease in the size of the pituitary

gland, often culminating in the development of an “empty sella.”

Anterior

hypopituitarism of varying severity occurs in patients with Sheehan syndrome,

depending on the extent of anterior lobe infarction. Loss of 90% of

adenohypophyseal cells frequently leads to life-threatening pituitary failure,

whereas loss of 50% to 70 % of anterior pituitary cells generally leads to

partial hypopituitarism. Central hypoadrenalism may result in shock that is

refractory to volume expansion and vasopressor administration. If loss of

pituitary function is partial and/or less severe, initial symptoms may be more

subtle, including failure to lactate and involution of breasts, followed by

postpartum amenorrhea. Other symptoms may include fatigue, weight loss, lack of

appetite, nausea, dizziness, and loss of axillary and pubic hair.

Sheehan

syndrome should be considered in women with severe postpartum blood loss

requiring blood transfusion.

Additional risk

factors include type 1 diabetes mellitus and sickle cell disease. In developed

countries, lymphocytic hypophysitis, occurring in the third trimester of

pregnancy or the postpartum period, has become more common than Sheehan

syndrome as a cause of new onset hypopituitarism in pregnancy and the

puerperium.

Once suspected, the diagnosis involves assays of systemic levels of target gland hormones, including morning serum cortisol, free thyroxine, estradiol, and gonadotropins. Serum prolactin levels may be very low in these patients. Stimulation testing may be needed to examine adrenocortical reserve and is essential in order to evaluate growth hormone secretion. Standard replacement therapies for pituitary hormone deficiencies are advised. In particular, prompt glucocorticoid replacement can be lifesaving. However, recovery of pituitary function is very uncommon.