Pituitary Apoplexy

Pituitary apoplexy denotes the presence of hemorrhagic necrosis of the pituitary, which generally occurs within a pituitary macroadenoma. In some cases, hemorrhage may occur within a cystic lesion (including Rathke’s cleft cyst). Rarely, pituitary apoplexy may occur as a result of hemorrhage within the pituitary gland in the absence of an adenoma or cyst. Pituitary apoplexy is a rare condition. In contrast, asymptomatic hemorrhage within a pituitary adenoma is not uncommon (occurring in approximately 15% of patients with pituitary adenomas).

Patients with

pituitary apoplexy present with severe headache of acute onset, which is

typically considered as the worst headache ever experienced. Nausea and

vomiting are very common. The rapid expansion of intrasellar contents

frequently leads to compression of the optic chiasm, causing visual field

defects. Lateral expansion resulting in compression of the nerves coursing

through the cavernous sinuses (including the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth

cranial nerves), fre- quently leads to diplopia, ptosis, facial pain, or

numbness. Increased intracranial pressure may occur, leading to impairment

in the level of consciousness. Interference with hypothalamic function may lead

to manifestations of sympathetic nervous system dysfunction, including

arrhythmias or disordered breathing.

In addition,

some of the blood may enter the subarachnoid space, leading to meningeal

irritation. Fever and neck stiffness may thus occur. Analysis of the

cerebrospinal fluid may reveal the presence of red cells and increased protein

content. It is therefore apparent that pituitary apoplexy should be considered

in the differential diagnosis of patients with suspected subarachnoid

hemorrhage or meningitis.

Life-threatening

pituitary failure may occur as a result of central hypoadrenalism (adrenal crisis).

Anterior hypopituitarism has been reported in up to 90% of patients with

pituitary apoplexy. In contrast, central diabetes insipidus is uncommon.

Pituitary

apoplexy is often spontaneous and often occurs at presentation of a pituitary

adenoma. Identified risk factors for the development of pituitary apoplexy

include trauma, anticoagulant use (including heparin or warfarin), coagulation

disorders, and administration of dopamine agonists (including bromocriptine or

cabergoline) or hypothalamic-releasing hormones.

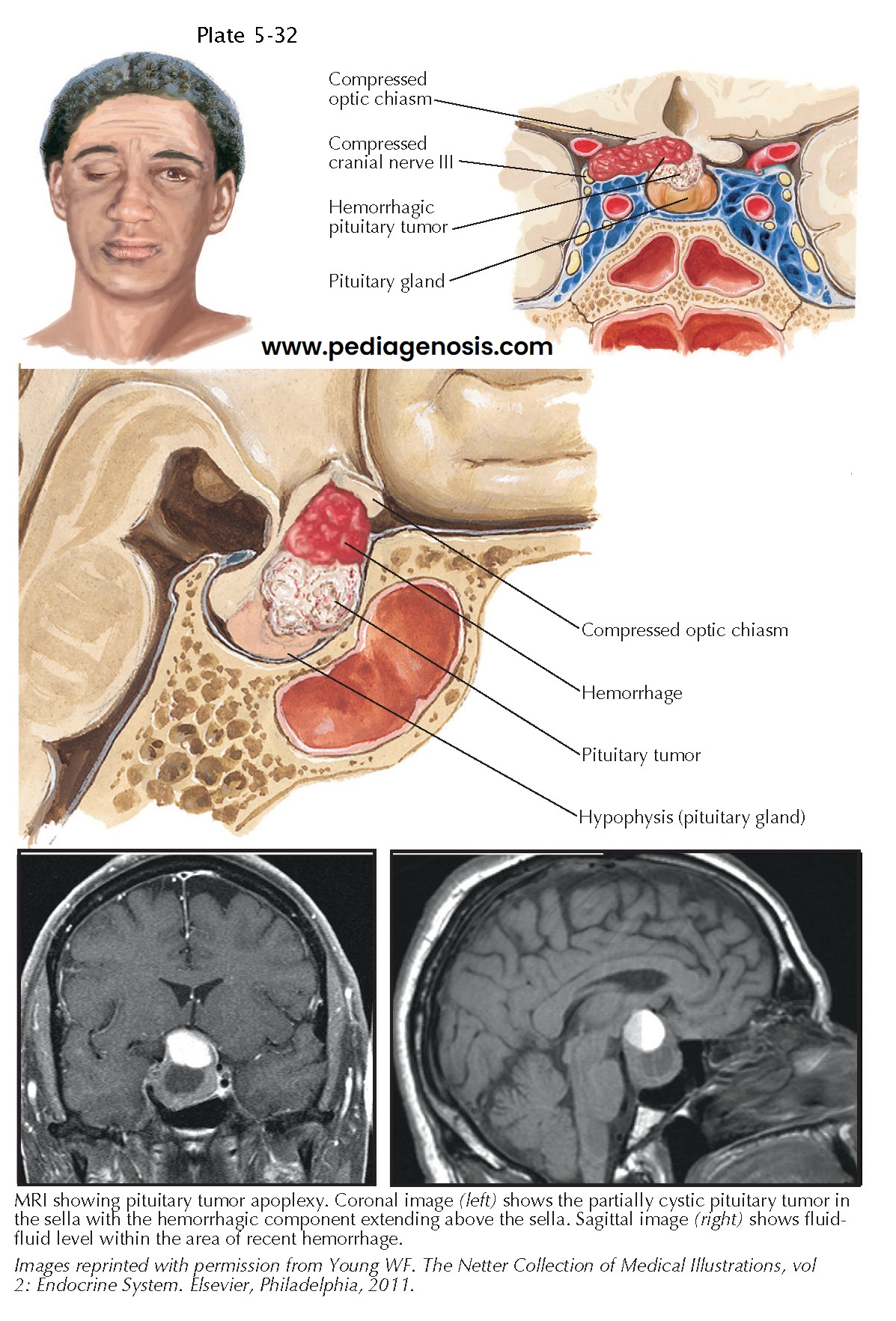

Magnetic

resonance imaging typically reveals a focus of hyperintensity (on noncontrast

T1-weighted images) within a sellar mass. A fluid-fluid level may also be

evident. Impingement on the optic chiasm or the cavernous sinuses is frequently

present. Laboratory testing usually reveals evidence of hypopituitarism.

Pituitary

apoplexy is a medical and neurosurgical emergency. These patients should be

hospitalized and receive at minimum a stress dose glucocorticoid coverage to

prevent the development of adrenal crisis. Of note, pharmacologic doses of

glucocorticoids are often administered to minimize acute pressure effects from

the hemorrhagic sellar mass on neighboring structures. Patients with impaired

level of consciousness or other evidence of increased intracranial pressure,

visual field defects, diplopia, or ptosis should be considered for early

(within 1 week) neurosurgical decompression, generally performed via the

trans-sphenoidal route. Early pituitary surgery is associated with more complete

recovery of visual field deficits than observation.

In contrast, patients who maintain a normal level of consciousness and show no evidence of increased intracranial pressure, visual field defects, or ophthalmoplegia may be observed. These patients may be considered for pituitary surgery if the sellar mass fails to regress considerably after the hemorrhage is reabsorbed. Pituitary function needs to be monitored and hormone replacement therapies advised as required. Hypopituitarism is often per anent, regardless of whether surgery is performed.