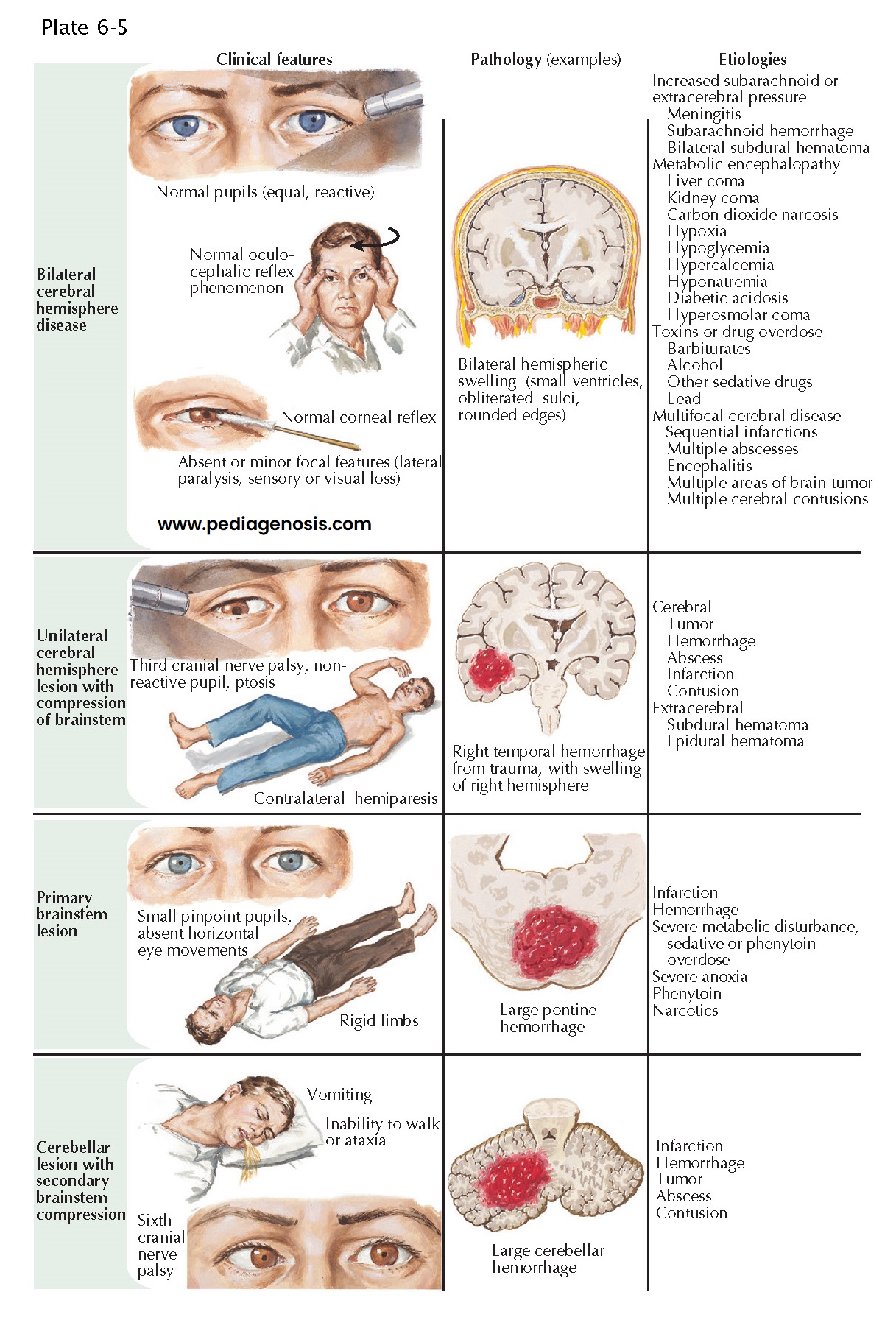

Differential Diagnosis of Coma

When coma is caused by bilateral cerebral hemisphere disease, swallowing, yawning, and spontaneous breathing are normal. The eyes rove spontaneously from side to side, and the limbs move symmetrically to stimulus. Pupillary and oculomotor reflexes are preserved. Toxic and metabolic disorders are the most common cause of coma resulting from bilateral hemisphere dysfunction. Encephalitis, hemorrhage, or infection in the meninges and subarachnoid space can also adversely affect bilateral hemisphere function. Although infarcts, hemorrhages, tumors, or abscesses can involve both hemispheres, the neurologic deficit becomes bilateral only sequentially.

When a hemispheric

lesion compresses the brain-stem, the patient usually has signs or symptoms

of hemisphere dysfunction, such as hemiparesis. Any space-occupying lesion,

such as subdural hematoma, infarction, hemorrhage, or tumor, may compress the

rostral brainstem and cause coma. As the lesion enlarges, intracranial pressure

rises, and headache, vomiting, decreased alertness and papilledema develop.

Signs of rostral brainstem diencephalic dysfunction follow. The midbrain and

pons are disrupted sequentially, and signs of lower brainstem failure are added

to dysfunction of rostral structures.

An intrinsic

brainstem lesion can cause coma by compromising the function of the medial

tegmental structures bilaterally. Primary diencephalic brainstem lesions are

usually due to stroke, either hemorrhagic or infarction. Head trauma may also

directly injure the brain-stem. In midbrain lesions, the pupils are

dilated or in midposition, and bilateral oculomotor nerve palsy occurs. The

eyes rest downward and outward and do not adduct or move vertically.

Decerebrate posturing of the limbs is present. Pontine infarct or hematoma cause

small, poorly reactive pupils and impaired vertical gaze. The eyes may rest

downward and inward, and one eye may be lower than the other. Brainstem

function rostral to the lesion is preserved. Pontine lesions cause

small, reactive pupils, failure of horizontal eye movements, preservation of

vertical eye movements (sometimes with spontaneous bobbing), and decerebrate

posturing. Medullary lesions may compromise vasomotor control and

breathing. Toxic disorders affecting the brainstem and cerebral hemispheres at

multiple levels cause signs inconsistent with any single anatomic locus.

Cerebellar

space-occupying lesions cause ataxia and vomiting, often followed by abducens

(cranial nerve VI) nerve or lateral gaze palsy to the side of the lesion. Signs

of lower brainstem dysfunction in the pons and medulla then develop.

TREATMENT

If a cerebral

or cerebellar lesion compresses the brain-stem, immediate treatment is required

to avoid irreversible injury. With a primary brainstem lesion, the situation is

equally urgent. Neuroradiologic investigations are critical in determining the

nature and extent of pathology. Endotracheal intubation, controlled mechanical

ventilation, and osmotic diuresis are undertaken while cranial computed

tomography (CT) is performed to determine whether the patient requires

immediate surgical decompression, cerebrospinal ventricular drainage, or

hematoma evacuation as lifesaving measures.

Bilateral cerebral hemisphere disease is usually treated medically rather than surgically. It is often the result of metabolic encephalopathy from exogenous intoxication, for instance, drug overdose, alcohol intoxication, or overmedication. Endogenous intoxication is caused by organ failure (the lungs and carbon dioxide narcosis; the liver and hyperammonemia; the kidney and uremia), hyperglycemia, hypercalcemia, or hypernatremia, or by insufficiency of endogenous or exogenous, for instance, hypoglycemia, hypothyroidism, ypocalcemia, or hyponatremia.