COMMON NAIL DISORDERS

|

| COMMON FINGERNAIL DISORDERS |

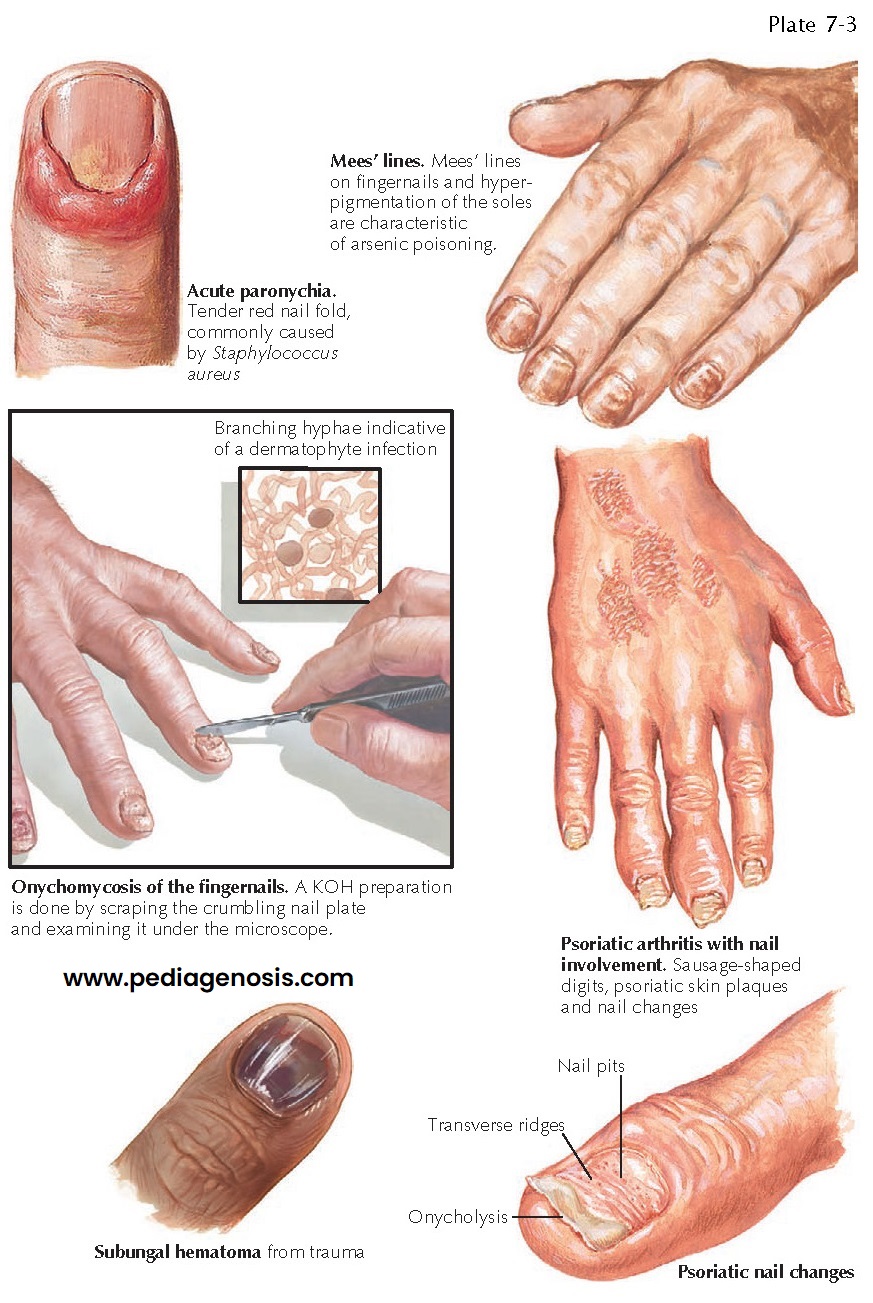

Nail disorders are frequently encountered in the clinical setting. They can occur secondary to an underlying systemic disorder or as a primary disease of the nail unit. The nail unit consists of the nail matrix, bed, and plate and the proximal and lateral nail folds. Disorders of the nail plate and nail bed can manifest in a variety of ways. Systemic disease can manifest through changes in the nail unit. Beau’s lines and Mees’ lines of the nail are two nail findings seen in systemic disease. Beau’s lines are caused by a nonspecific halting of the nail matrix growth pattern, and Mees’ lines are specific for heavy metal toxicity. Dilation of the capillaries of the proximal nail fold or cuticular erythema can be a sign of connective tissue disease. The complete skin examination should also include an examination of the nails, because they offer insight into the patient’s health.

One

of the most serious nail unit disorders is melanoma of the nail matrix.

Melanoma may manifest as a linear, pigmented band along the length of the nail.

As time progresses, the proximal nail fold and hyponychium may also become

pigmented and involved with melanoma. The finding of pigment on the proximal

nail fold has been termed Hutchinson’s sign. This sign is not seen in

subungual hematomas. All new pigmented nail streaks should be evaluated and a

biopsy considered. The biopsy requires nail plate removal and retraction of the

proximal nail fold. The biopsy of a pigmented nail streak is performed within

the nail matrix. Biopsies of the nail matrix may lead to a thinner nail or to

chronic nail dystrophy due to disruption of the matrix. Subungual melanoma

tends to be diagnosed late, because these tumors are easily overlooked or

passed off as a subungual hematoma. It is critically important to differentiate

the two.

Subungual

hematomas are frequently encountered. Most are caused by direct trauma to the

nail plate and nail bed, which causes bleeding between the plate and bed. Acute

hematomas can be very painful. Most acute subungual hematomas are on the

fingers and are caused by a crush injury or by a direct blow to the nail plate.

As the blood accumulates under the nail plate, the pressure created can cause

excruciating pain. This can be easily treated by nail trephination. A

small-gauge hole is bored into the overlying nail plate with a hot, thin metal

object or small drill. Once the nail plate has been punctured, the blood that

has accumulated under the nail freely flows out of the newly formed channel, and

near-immediate pain relief is achieved. Most traumatic injuries to the nail

unit do not cause these very painful hematomas but rather cause small amounts

of blood to accumulate under the nail plate. Pain is absent or minimal. Most

people remember some trauma to the nail, but others do not. This form of

subungual hematoma can involve small portions of the nail or the entire nail.

There is often a blue, purple, and red discoloration of the underlying nail.

Occasionally, the nail plate has a black appearance and is easily confused with

subungual melanoma. The history can be misleading in these cases, because many

patients with and without melanoma remember some form of trauma to the nail

that might lead the clinician to pass the lesion off as a subungual hematoma.

If any doubt about the diagnosis exists, a nail biopsy should be considered.

The nail plate is removed, and a subungual hematoma is easily distinguished

from a tumor. Most subungual hematomas slowly grow outward toward the distal

free edge of the nail. As the nail grows, its most proximal portion appears

normal. The entire subungual hematoma eventually grows out and is shed or

clipped off once it passes the hyponychium.

Onychocryptosis

(ingrown nail) is almost universally seen in the great toenail. It is caused by

burrowing of the lateral portion of the nail plate into the lateral nail fold.

As the nail punctures the lateral nail fold, it sets off an inflammatory

reaction that causes edema, redness, pain, and occasionally purulent drainage.

Secondary infection is common. Ambulation may become difficult because the pain

forces the patient to avoid pressure.

The

exact etiology of onychocryptosis is not entirely known, but it is believed to

be caused, or at least made more likely, by improper trimming or removal of the

lateral portion of the nail. If the nail plate is cut at varying angles or torn

from its bed by picking, this may allow for the lateral free edge of the nail

plate to enter into the lateral nail fold. Tight-fitting shoes have also been

implicated as increasing the likelihood of developing ingrown nails. This

condition is seen more frequently in young men, but it can be seen in all age

groups. The fingernails are rarely affected. Treatment consists of lateral nail

plate removal with or without a lateral nail matrixectomy. After proper

anesthesia, a nail plate elevator is used to free the involved portion of the

nail. A nail splitter is then used to remove the lateral third of the nail. The

freed nail is grasped with a nail puller, and the nail is removed with a

gentle, back-and- forth rocking motion. The portion of the nail that is removed

from under the lateral nail fold is often larger than expected. Recurrent

ingrown nails usually should be treated with nail matrixectomy. This destroys

the lateral third of the nail matrix, eliminating the ability to form that

portion of the nail and removing the potential nidus from causing further

problems in the future. Application of phenol to the nail matrix after nail

plate avulsion is one of the best methods for destroying the nail matrix.

Bilateral nail fold involvement on the same toe is not infrequently

encountered, and the entire nail can be removed in these cases. Onychocryptosis

is not a primary infection of the nail unit, and any infection is believed to

be secondary to the massive inflammatory response. This is in stark contrast to

an acute paronychia.

|

| COMMON TOENAIL DISORDERS |

Paronychia

is a nail fold infection with either a bacterial agent (as in acute paronychia)

or a fungal agent (in chronic paronychia). Acute paronychia manifests with

redness and tenderness of the nail fold. The redness and edema continue to

expand, causing pain and eventually purulent drainage. Removal of the cuticle

or nail fold trauma may lead to an increased risk for this infection. Staphylococcus

aureus and Streptococcus species are the most frequent etiological

agents. Chronic paronychia typically is less inflammatory and manifests with

redness and edema around the nail folds. Many digits may be involved. At

presentation, patients typically report that they have been having difficulty

for longer than 6 to 8 weeks. Tenderness is much less significant than in acute

paronychia. Chronic paronychia is usually caused by a fungal infection of the

nail fold with Candida albicans. Individuals who work in occupations in

which their hands are constantly exposed to water are at higher risk for

chronic paronychia. Therapy includes topical anti-fungal and antiinflammatory

agents.

A

felon is often confused with acute paronychia, but it is a soft tissue

infection of the fingertip pulp. It may arise secondary to an acute paronychia.

The clinical findings are those of a swollen, red, painful finger pad. The

treatment is surgical incision and drainage together with oral antibiotics to

cover S. aureus and Streptococcus species.

Onychomycosis

is seen frequently in individuals of all ages, and its prevalence increases

with age. Patients can present with different variants of onychomycosis. The

most frequent type is the distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis. Other

variants include white superficial onychomycosis and proximal subungual

onychomycosis. Trichophyton rubrum is the most frequent cause of all

except white superficial onychomycosis, which is caused most often by Trichophyton

mentagrophytes. Superficial white onychomycosis manifests with a fine,

white, crumbling surface to the nail.

When

it is curetted off, the white areas of fungal involvement are found to affect

only the outermost portion of the nail plate. The material is a combination of

fungal elements and nail keratin. Therapy includes curetting the white involved

portion of the nail and applying a topical antifungal agent for at least 1

month. Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis manifests with thickened,

yellow, dystrophic appearing nails with subungual debris. There are varying

amounts of onycholysis (nail plate lifting off the nail bed). One nail may be

solitarily involved but it is more common for several nails to be involved and

for the surrounding skin to be involved with tinea manuum or tinea unguium.

Fungal nail infections are much more frequently seen on the toenails than on

the fingernails. The nails can become painful, especially with ambulation.

Occasionally, the entire nail is shed as a result of significant onycholysis,

and the nail that regrows will again be involved with onychomycosis. The thick

and dystrophic nails may become a passage for bacterial invasion of the body.

This is especially true in patients with diabetes. Bacteria can gain entrance

into the skin and soft tissue via the abnormal barrier between nail and nail

fold, and this can lead to paronychia, felon, and the most serious

complication, cellulitis. Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis almost

always needs to be treated with an oral antifungal medication for any chance of

a cure. Topical agents may be helpful in limited nail disease, but their use is

typically limited to an adjunctive role. Oral azole antifungals, griseofulvin,

and terbinafine have all been used, with similar results. Psoriasis can affect

the nails in many ways. Nail involvement appears more frequently in patients

with severe disease and in those with psoriatic arthritis. The nails can show

oil spots, pitting, ridging, onycholysis, and onychauxis (subungual

hyperkeratosis). The oil spots are represented by a brownish to yellowish discoloration under the nail plate and associated onycholysis. The discoloration

is caused by deposition of various glycoproteins into the nail plate. Nail

pitting can be seen in other conditions besides psoriasis, such as alopecia

areata; it is caused by parakeratosis of the proximal nail matrix, which is

responsible for producing the dorsal nail plate. Ridging and onychauxis is

caused by the excessive hyperkeratosis of the nail bed, which is directly

caused by psoriasis. Therapy for psoriatic nails can involve intralesional

steroid injections or use of systemic agents to decrease the abnormal immune response that

is driving the psoriasis. Onychogryphosis (“ram’s horn” nail deformity)

manifests with an unusually thickened and curved nail that takes the shape of a

ram’s horn.

A

plethora of nail changes may be seen in response to systemic disease. Beau’s

lines are horizontal notches along the nails that may be caused by any major

stressful event. The stressful event typically is induced by prolonged

hospitalization, which causes temporary inadequate production of the nail bed

by the nail matrix. It is entirely corrected spontaneously as the individual

improves. Mees’ lines are induced by heavy metal toxicity, most commonly from

arsenic exposure. They appear as a single, white horizontal band across each

nail. Mees’ lines have also been reported in cases of malnutrition. Terry’s

nails is the name given to nail changes seen in congestive heart failure and

cirrhosis of the liver: More than two thirds of the proximal nail plate and bed

appear dull white with loss of the lunula. Half-and-half nails, also called

Lindsay’s nails, are seen in patients with chronic renal failure. The proximal

half of the nail is normal appearing, whereas the distal half has a brown

discoloration. Yellow nail syndrome manifests with all 20 nails having a

yellowish discoloration and increased thickness of the nail plate. This syndrome

is almost always seen in association with a pleural effusion, often secondary

to a lung-based malignancy.

Koilonychia is one of the most easily recognized deformities of the nail; it is caused by iron deficiency. The nail plate develops a spoon-shaped, concave surface. Splinter hemorrhages may be a sign of bacterial endocarditis. Clubbing, which is defined as loss of Lovibond’s angle, is typically caused by chronic lung disease. The nail unit can manifest disease in many ways, and awareness of the various nail signs can help the clinician diagnose and treat these conditions.