Visual Inputs to the Hypothalamus

The

hypothalamus is largely framed by the optic chiasm, which underlies its most

rostral part (the preoptic area) and provides the lateral boundary for its

middle, tuberal part. Despite this close relationship, it remained a mystery

for many years how the hypothalamus used visual input to synchronize its

biologic clock with the external world. In 1972, two groups of scientists

demonstrated that some axons leave the optic chiasm as it passes by the hypothalamus

and provide an input that is now called the retinohypothalamic tract.

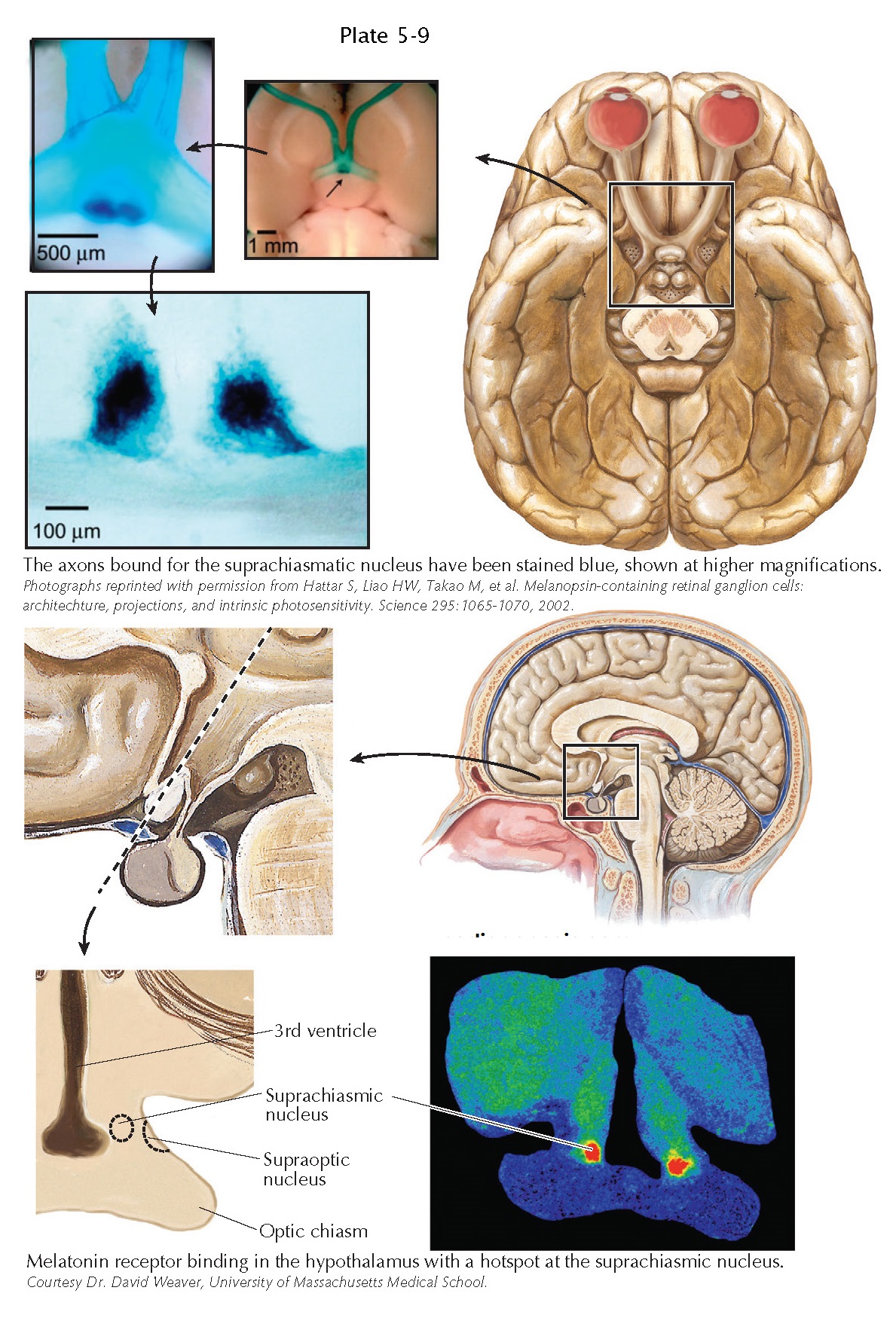

The retinohypothalamic tract originates from about 1,000 scattered retinal ganglion cells in each retina. In 2001, it was discovered that these retinal ganglion cells have the peculiar property of making their own light-sensing pigment, called melanopsin. So, although other retinal ganglion cells that are concerned with patterned vision are “blind” and depend upon input from rods and cones to signal to them the presence of light in their receptive fields, the melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells are intrinsically photosensitive. These neurons act essentially as light level detectors and relay this information both to the hypothalamus as well as to the olivary pretectal nucleus, which is a criti- cal relay in the pupillary light reflex pathway.

By replacing

the melanopsin gene with one for β-galactosidase, one can

then stain the melanopsincontaining retinal ganglion cells blue and follow

their axons into the brain. The densest site of retinohypothalamic input is to

the suprachiasmatic nucleus, although other axons, in smaller numbers, enter

other parts of the hypothalamus. The suprachiasmatic nucleus is the brain’s

biologic clock; damage to this cell group causes animals and humans to lose

their 24-hour patterns of activity in wake-sleep, feeding, body temperature,

corticosteroid secretion, and other important physiologic and behavioral

functions. Although the neurons in the suprachiasmatic nucleus maintain an

approximately 24-hour rhythm of activity even when placed into tissue culture,

retinal input is necessary to reset their clock rhythm to maintain synchrony

with the external world. In the absence of light cues, circadian rhythms in

both people and animals show a free-running cycle that is generally just a bit

different from 24 hours and may vary among individual (humans average about

24.1 hours). Although this may seem like a small difference from 24 hours,

without a mechanism for synchronization, someone with a 24.1-hour cycle would

be 3 hours off-cycle from the rest of the world by the end of 1 month. Some

blind individuals, with total loss of retinal input to the brain, show this

type of shift of their circadian rhythms over time so that they go through

periods every few months where their cycles go out of phase with the rest of

the world. Other blind people, such as those with rod and cone degeneration,

who retain intrinsically photosensitive melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion

cells, remain in synchrony with the world that they cannot see.

Melatonin is

one of the hormones whose 24-hour cycle of secretion is driven by the

suprachiasmatic nucleus. Suprachiasmatic axons directly contact neurons in the

paraventricular nucleus, which, in turn, inner-vates the sympathetic

preganglionic neurons in the upper thoracic spinal cord. The latter project to

the superior cervical ganglion, which sends axons along the internal carotid

artery intracranially to innervate the pineal gland, causing secretion of

melatonin. The hormone is mainly secreted at the onset of the dark period and

in humans may promote sleepiness. One of the major targets in the brain for

melatonin is the suprachiasmatic nucleus itself, which stands out when the

brain is stained for melatonin receptors.

Other retinal axons to the hypothalamus may be important in providing visual inputs to neurons con-cerned with a variety of diverse functions. For example, retinal inputs to a sleep-promoting cell group, the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, may explain why people turn out the lights and close their eyes when falling asleep. Other inputs to the lateral hypothalamus may contact neurons involved in regulating arousal and feeding. In rodents, who might be recognized as potential prey when they venture into a lighted area, an important response to light is immobility. This reduced locomotion in light appears to be reg lated by retinal inputs to the subparaventricular zone.