REHABILITATION AFTER SPORTS

INJURY

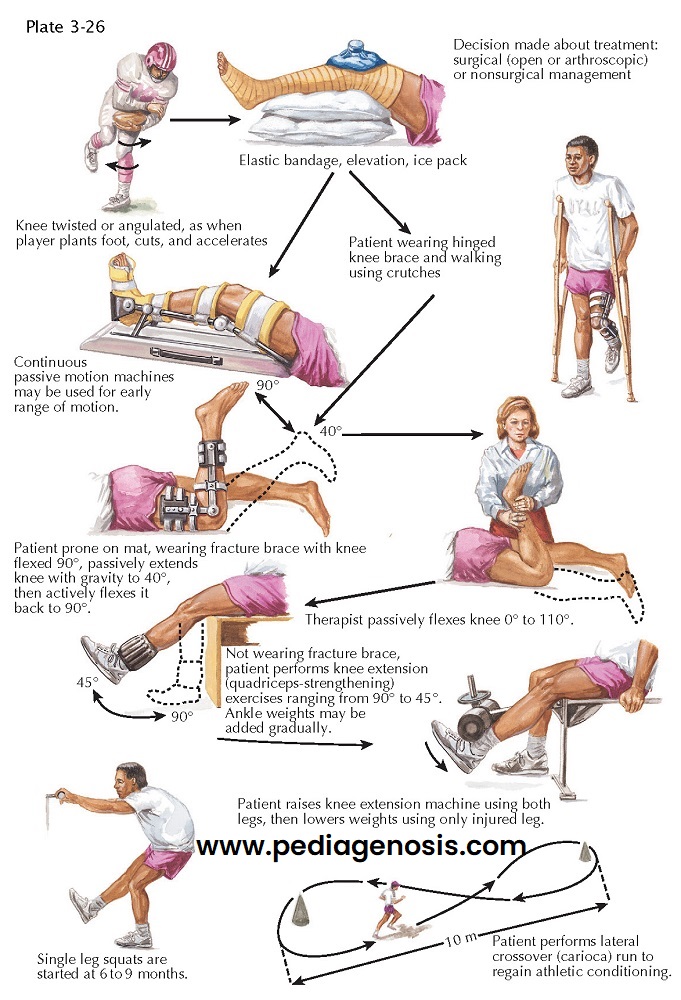

The goal of conservative management of ligament injuries of the knee is to stabilize the action of the knee with the remaining uninjured, supportive structures. Rehabilitation must begin as soon as possible after injury, because disuse atrophy of the muscles occurs rapidly. Rehabilitation focuses on muscle strengthening, particularly strengthening of the extensor (quadriceps) muscles and the flexor (medial and lateral hamstring) muscles.

The knee is flexed in an arc of motion between 30 and

90 degrees, avoiding full extension. Resistance is applied in the pain-free

portion of the range of motion, with the tibia internally and externally

rotated to strengthen the hamstring muscles. The exercises can be done with the

patient prone or standing.

Isokinetic resistance is also initiated, starting at

slow speeds and gradually increasing. Isotonic, isometric, or isokinetic

extension of the knee may also be initiated. The knee should remain pain free

through the entire arc of motion. End-arc discomfort may occur. Extension

exercises are begun with the starting position at less than 90 degrees of

flexion and termination at less than full extension. Hip flexion and abduction

exercises can be isometric or isotonic. Double-foot raises (raising both heels

off the floor simultaneously) in sets of 50, done with the knee slightly bent,

strengthen the gastrocnemius muscles that help stabilize the knee.

Endurance training should be added to initiate

cardiovascular conditioning. Use of a stationary bicycle, with the resistance

set at zero, is effective and also improves the range of motion in the knee.

Once the knee is pain free, the resistance can be increased for further

cardiovascular benefits.

Postoperative rehabilitation after surgical

reconstruction of the knee consists of a progressive program that is conducted

in stages. Immediately after surgery, the knee is typically placed in a hinged

fracture brace to allow controlled motion, unless the patient is in a

continuous passive motion machine. Although there is no definitive evidence of

the long-term improvements in outcome using continuous passive motion, the

theory is that it will increase mobilization, decrease pain, reduce swelling,

prevent adhesions, improve proprioceptive function, and allow for a more rapid

return of joint range of motion.

The patient is then taught to use crutches with

progressive weight bearing on the affected side. This protected weight bearing

is continued until the surgeon is confident that the ligaments have healed.

During the healing phase, passive range-of-motion exercises should be supervised, with extension being passively assisted

by gravity pulling the leg toward an exercise mat and limited by the extension

stop of the brace. Active flexion exercises can be started with the patient

using the hamstring muscles. Straight-leg raises, flexion-to-extension

exercises within the safe range of limited motion, cocontractions, hip flexion

exercises, and leg curls are also started to maintain muscle tone and strength.

The amount of resistance and the number of sets or repetitions are gradually

increased as tolerated.

Usually, the brace can be discarded within 3 months after surgery, and the program for strengthening knee flexion and extension accelerated. By 6 months, a program to achieve full extension should have begun with slow, progressive resistance exercises, such as light squatting with the thighs parallel with the floor. Swimming is often encouraged to increase endurance. The patient should avoid running until the injured limb has regained at least 80% of the strength of the normal limb.