PUERPERAL

INFECTION

Puerperal infection generally refers to an infection of the genital

tract in the postpartum period. For centuries, puerperal infection was the

leading cause of maternal death, though this has changed dramatically with the

advent of antibiotics. Maternal death rates associated with infection account

for approximately 0.6 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Endometritis is

the most common form of postpartum infection, though other sources of

postpartum infections include postsurgical wound infections, perineal

cellulitis, mastitis, respiratory complications from anesthesia or under-lying

pulmonary disease such as asthma or obstructive lung disease, retained products

of conception, urinary tract infections, and septic pelvic phlebitis. Overall,

postpartum infection is estimated to affect 1% to 3% of normal vaginal

deliveries, 5% to 15% of scheduled caesarean deliveries, and 15% to 20% of

unscheduled caesarean deliveries.

The organisms responsible for the vast majority of puerperal infections are the anaerobic and aerobic nonhemolytic varieties of streptococci. These organisms are usually present in the birth canal, becoming pathogenic when carried to the uterine cavity during or after delivery.

Postpartum endometritis

is typically a polymicrobial infection (70% of cases) involving a mixture of

two to three aerobes and anaerobes from the genital tract. In most cases of

endometritis, the bacteria responsible are those that normally reside in the

bowel, vagina, perineum, and cervix. Commonly isolated organisms include Ureaplasma

urealyticum, Peptostreptococcus, Gard- nerella vaginalis, Bacteroides

bivius, and group B streptococci. Other, though less frequent, organisms

causing puerperal infection are Staphylococcus albus (Micrococcus

pyogenes), anaerobic organisms, and the colon bacillus (Escherichia coli).

Chlamydia has also been associated with late-onset postpartum

endometritis.

Inadequate asepsis during

labor and delivery, repeated vaginal examinations, and the use of contaminated

materials are avoidable factors in the pathogenesis. Coitus late in pregnancy

also has been considered to help disseminate inoculation and infection. Blood

loss and trauma are considered the most frequent predisposing causes of

puerperal infection. Trauma creates a portal of entry and produces a favorable

environment for the development of virulent bacteria. Prolonged labor, particularly

with early rupture of the membranes, retention of placental tissues and major

vaginal procedures producing vaginal and cervical lacerations may initiate or

foster puerperal infection.

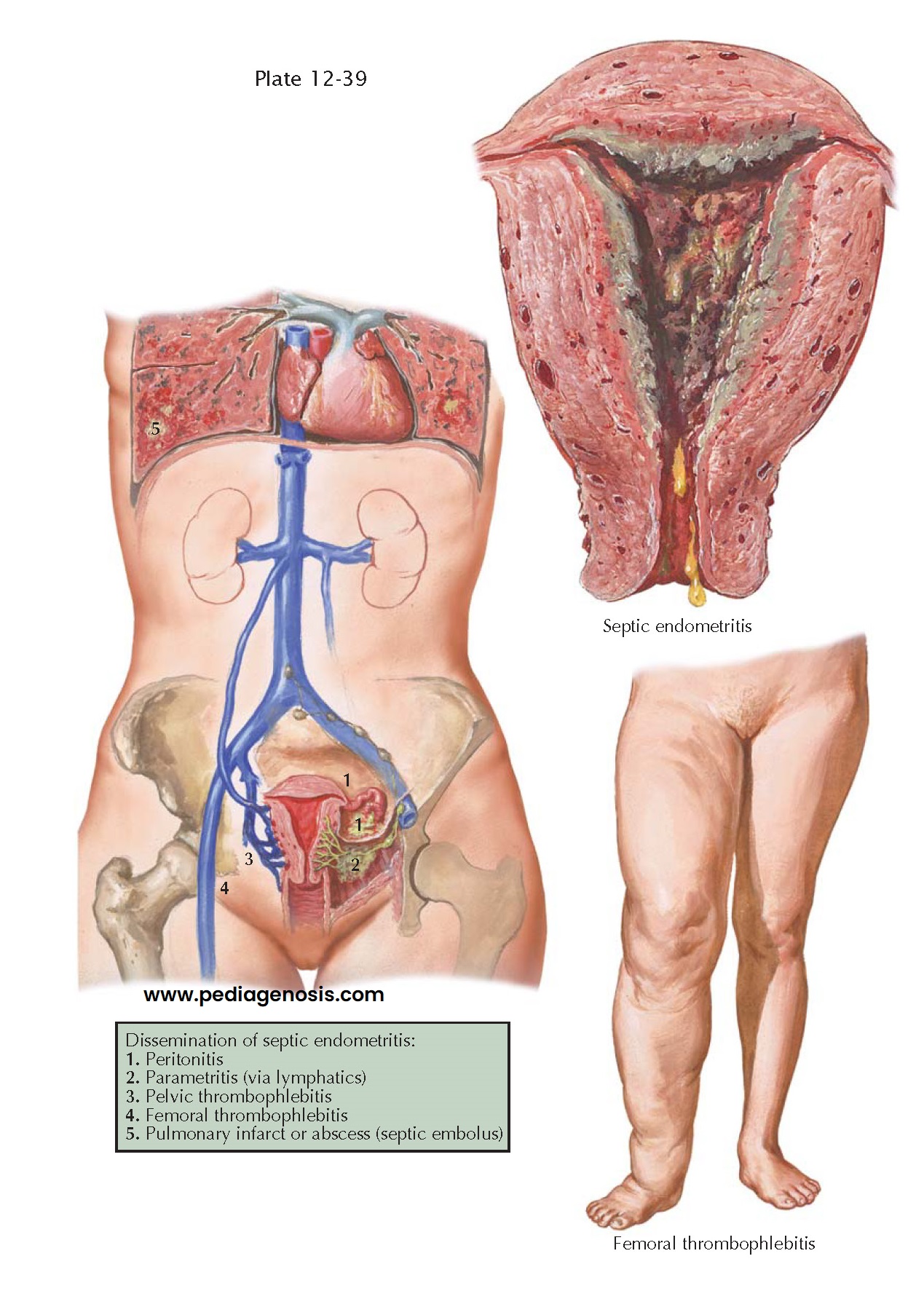

The pathologic findings in

puerperal infection are similar to those of any other wound infection.

Following delivery of the fetus and placenta, the endometrium favors bacterial

growth. Infection of the episiotomy and vaginal lacerations may occur, but

these are less frequent than endometritis. This latter is by far the most

frequent site of puerperal sepsis. The appearance of the endometrium and its

discharge vary according to the infecting organisms. It usually appears

necrotic and yellowish green but may be black from decomposed blood. The

inflammatory process may remain in the uterine cavity, spread to the parametrial

tissues, or become widely disseminated. From the endometrium, the inflammatory

process may extend along the uterine and other pelvic veins, resulting in

pelvic thrombophlebitis. Thrombophlebitis of the leg veins may also be seen. Extension of the inflammation

through the lymphatic channels to the parametrial tissues and peritoneum

results in parametritis, pelvic cellulitis, and peritonitis. Distant spread to

lungs or liver may occur in the form of septic emboli and therewith cause

septic infarcts and abscesses.

The diagnosis is usually made without difficulty. Fever occurring in the postpartum period, accompanied by lower abdominal tenderness, should be considered to be a puerperal infection until proved otherwise. Extreme abdominal and uterine tenderness together with rigidity of the abdominal walls and absence of peristalsis are indicative of generalized peritonitis. The character and odor of the lochia may help in making the diagnosis and sometimes in recognizing the organisms. Some infections, notably those caused by group A-hemolytic streptococci, may be associated with scanty, odorless lochia.