PREECLAMPSIA

IV-PLACENTAL

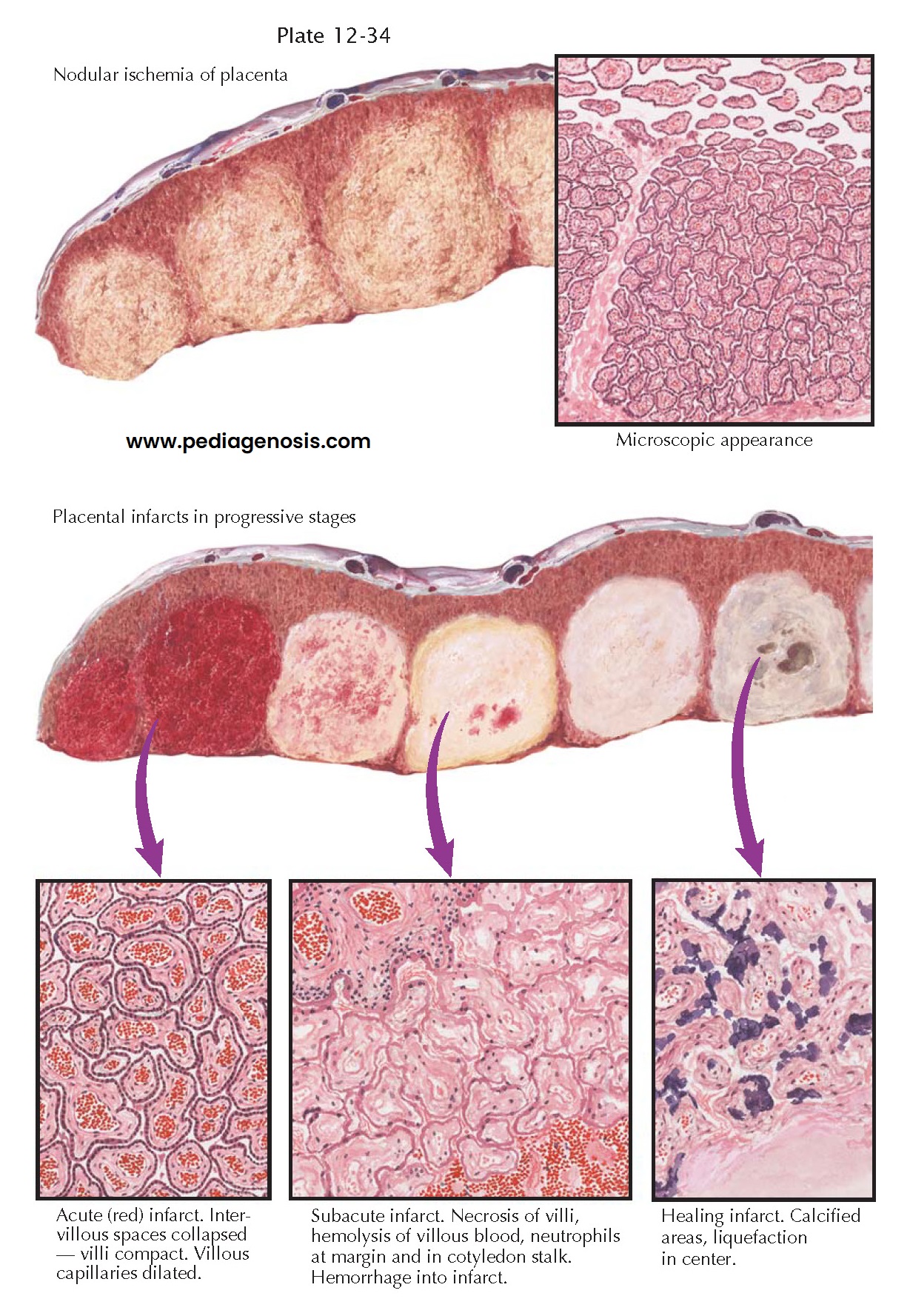

INFARCTS

Because preeclampsia is a

condition peculiar to pregnancy, and because delivery usually results in the

rapid regression of the signs, symptoms, and pathologic lesions, it would seem

reasonable to believe that the contents of the gravid uterus either may be the

source of the vasoconstrictor factor or may play an important role in leading

to the production of that factor elsewhere in the body. The fetus is not a

required factor, because severe preeclampsia occasionally accompanies

hydatidiform mole. Therefore, the trophoblastic tissue or the gravid

endometrium would seem to be incriminated. Despite this, there are no micro- or

macroscopic placental lesions that are pathognomonic for preeclampsia.

Pathologic studies have revealed close correlation between the occurrence of preeclampsia and conditions that are prone to cause a decrease in the maternal circulation to the placenta, to the decidua, or to both of these tissues. Obstruction of the maternal blood flow to one or more placental cotyledons causes true infarction of the involved areas. Unfortunately, the term infarct has often been used for a wide variety of nodular lesions in the placenta, and conflicting opinions have been expressed concerning the association of such lesions with preeclampsia.

True infarcts are usually

found on the maternal aspect of the placenta but are often not visible until

cross sections are made. They then appear as round or oval nodules of increased

density and may be varying shades of red, yellow, or gray, according to their

age. Microscopically, they consist of necrotic chorionic villi. Immediately

after cessation of the maternal blood flow to a cotyledon, the intervillous

spaces collapse. The part becomes pale and of increased density. This is called

nodular ischemia. The areas with more venous blood beneath the chorionic plate

and between the cotyledons are less affected than the centers of the nodules.

If the fetus is alive, dilation and filling of the unobstructed villous

capillaries ensue, and, thus, the part becomes congested and an acute red

infarct is produced. If the fetus is dead, the infarct remains ischemic. In

either case, as the villi become necrotic, the nuclei undergo karyorrhexis and

karyolysis, the red cells become hemolyzed, and the entire area takes on a

yellowish hue. A reaction zone of neutrophils forms at the margin between the

dead and living tissue, appearing as a dense ring around the lesion. This is

called the subacute stage of infarction.

Infarcts in the placenta

do not heal by organization. No fibroblastic proliferation or budding of

capillaries has been found in the many examples of old infarcts examined.

Calcium is deposited at the periphery of the lesions, which become gray or

white as they age. The centers are prone to liquefy and become cystic.

Because cotyledon stalks

bearing large fetal vessels are often included in the depths of large infarcts,

the fetal circulation continues until necrosis of the supporting tissues causes

rupture and hemorrhage of fetal blood into the necrotic area. If the hemorrhage

is extensive, it may rupture

retroplacentally and be a factor in the initiation of premature separation.

This can also result in exposing the mother to fetal blood antigens such as Rh

(D).

Studies carried out in the past several years have shown no significant difference between the placentas of pregnancies complicated with preeclampsia/eclampsia and control groups with regard to ischemic changes of the placenta. Endovascular trophoblastic plugs in the basal plate vessels may play an additional role in the development of ischemic lesions in preeclampsia/ eclampsia, but these may also represent indirect evidence of the abnormal expression of certain adhesion molecules in this disorder. In preeclampsia, trophoblast invasion is impaired and this, along with endothelial dysfunction, has been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia, but support for this has been variable and inconsistent.