PREECLAMPSIA

I—SYMPTOMS

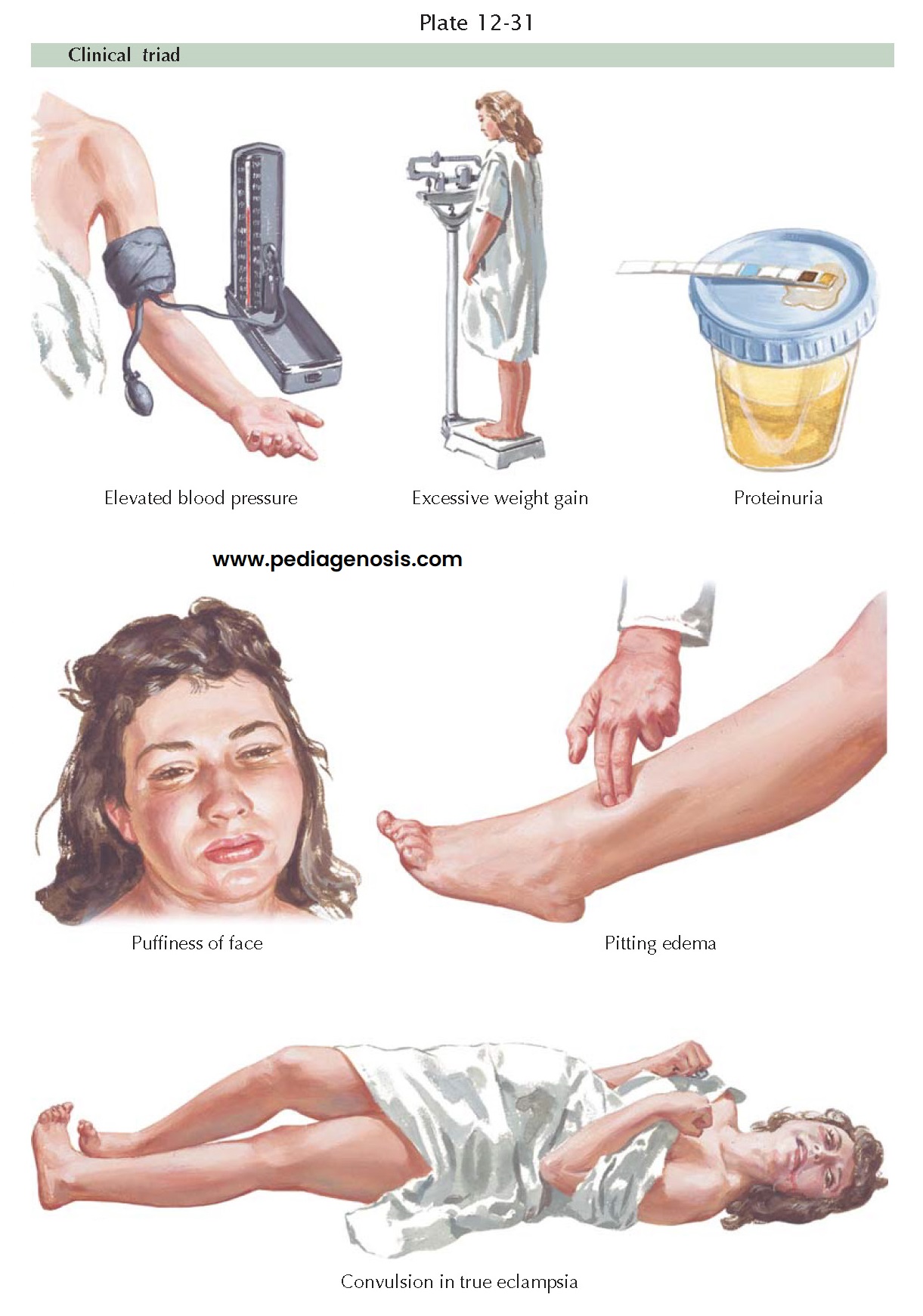

Preeclampsia (once called toxemia of pregnancy) is a

pregnancy-specific syndrome occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation. It involves

reduced organ perfusion, vasospasm, and endothelial activation and is

characterized by hypertension, proteinuria, and other symptoms. Pregnancy can

induce hypertension or aggravate existing hypertension. Edema and proteinuria

(one or both) are characteristic pregnancy-induced changes. If pre-eclampsia is

untreated, convulsions (eclampsia) may occur. Chronic hypertension may be

worsened by being superimposed on pregnancy-induced changes. Severe cases may

include hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet counts, labeled

HELLP syndrome, which occurs in up to 20% of severe preeclampsia. Preeclampsia

occurs in 5% to 8% of all births (250,000 cases per year) and results in 150

maternal deaths and 3000 fetal deaths per year. (Overall, hypertensive disease

of some type occurs in approximately 12% to 22% of pregnancies, and it is

directly responsible for 17.6% of maternal deaths in the United States.)

In the great majority of cases, the clinical manifestations of preeclampsia occur after the 20th week of gestation and disappear following delivery. Preeclampsia before 20 weeks’ gestation may occur with gestational trophoblastic neoplasia and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Another uncommon presentation for pre-eclampsia is in the postpartum period, when it has been reported to occur up to 7 days after delivery.

The earliest clinical

signs of preeclampsia are often sudden and excessive weight gain, accompanied

by a blood pressure higher than 140/90 mmHg and by proteinuria. Such weight

gain reflects the retention of water and electrolytes. Eventually, pitting

edema, particularly in the legs and face, develops. However, before the stage

of pitting edema is reached, the interstitial space may accumulate large

quantities of fluid. The normal average weight gain during pregnancy does not

exceed 2½ to 3 lb per month, and a greater weight gain should be suspected as

abnormal water retention. Edema may precede hypertension, but for the clinical

diagnosis of preeclampsia, the increased blood pressure is essential. In this

respect the elevation of the diastolic blood pressure is more significant than

that of the systolic, because it is the former which reflects the status of the

peripheral resistance.

The criteria needed to

diagnose a patient with pre-eclampsia include the results of 24-hour urinary

protein measurement that demonstrate >300 mg of protein in 24 hours. In

addition, these patients have blood pressure measures above 140/90 mm Hg. These

patients also have characteristic renal glomerular lesions (capillary

endotheliosis) and increased vascular reactivity. They often manifest elevated

liver enzymes, and thrombocytopenia. In the past, hypertension indicative of

preeclampsia has been defined as an elevation of more than 30 mm Hg systolic or

more than 15 mm Hg diastolic

above the patient’s baseline pressure; however, this has not proven to be a

good predictor of outcome and is no longer part of the criteria for

preeclampsia, though these patients do require close monitoring. Pre-eclamptic

patients may undergo convulsions with only moderate blood pressure elevation

and only a slight degree of edema.

Conscientious, regular prenatal care is important in order to detect signs of preeclampsia as early as possible. The onset of preeclampsia may be insidious or abrupt. The patient may feel well and not be aware of abnormal weight gain, proteinuria, or rising blood pressure. There may be a sudden progression into the convulsive phase, necessitating the termination of the pregnancy, thereby resulting in prematurity of the infant, which is the most frequent cause of perinatal mortality in preeclampsia. It is thought that severe preeclampsia predisposes to chronic hypertensive vascular disease, and the incidence of severe preeclampsia in subsequent pregnancies is increased.