PREECLAMPSIA

II— OPHTHALMOLOGIC CHANGES IN PREECLAMPSIA AND

ECLAMPSIA

Visual disturbances are very frequent in

eclampsia and preeclampsia. (Ocular sequelae have been reported in up to one

third of cases.) They range from slight blurring of vision to various degrees

of temporary blindness. Other symptoms have also been noted, including

photopsias, scotomas, and diplopia. These disturbances are thought to be caused

by the arteriolar spasm of the retinal vessels together with ischemia, edema,

and sometimes retinal detachment. In some patients with visual changes in

preeclampsia, a diffuse increase in macular thickness has been documented.

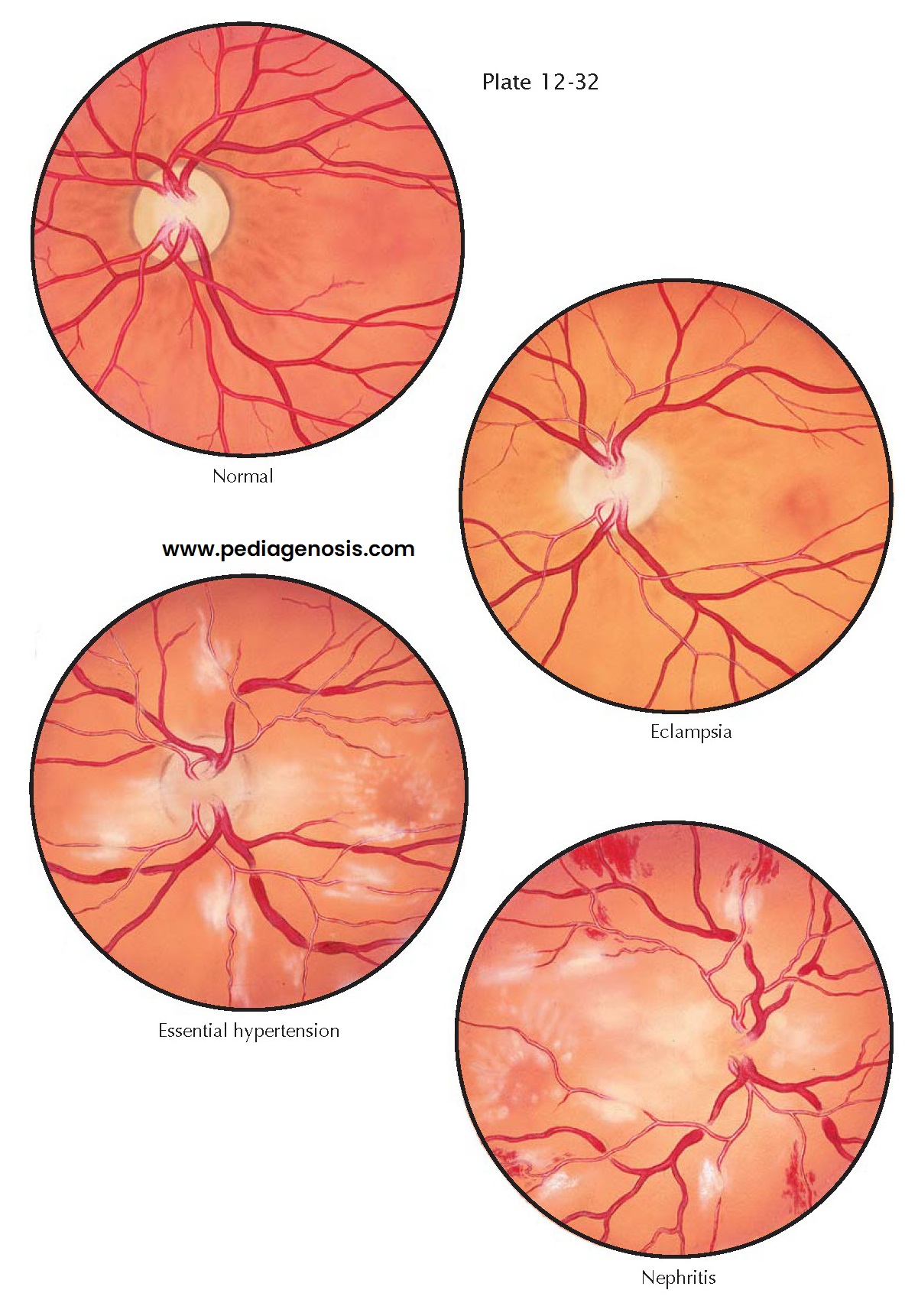

Examination of the eye grounds is of great help in the differential diagnosis between preeclampsia, eclampsia, and other hypertensive states coexisting with pregnancy. In preeclampsia, the first change in the retinal vessels consists of a spasm of the arterioles. The constriction is usually localized in certain areas of the retinal vessels. A series of sausage-linked or spindle-shaped constrictions may be seen in the terminal part of the retinal vessels or sometimes in the part close to the disk. The changes are seen more frequently in the nasal branches. Occasionally, all the retinal vessels are seen constricted to a marked degree.

In order to observe

clearly the changes in these vessels, dilation of the pupils with atropine or

an equivalent drug is essential. Comparison of the ratio of the diameter of the

retinal arterioles to the retinal veins is informative. In normal individuals,

the ratio of the arterioles to the veins is 2:3. In preeclampsia, this ratio

may change to 1:2 or even 1:3, indicating extreme narrowing of the retinal

arterioles.

Edema of the retina may

be seen occasionally in preeclampsia and eclampsia, but it is much less

frequent than spasm of the vessels. The edema usually appears first at the upper

and lower poles of the disk and later progresses along the course of the

retinal vessels. In rare instances, retinal edema becomes so intense that

complete detachment of the retina occurs.

Hemorrhages and exudates

are rarely seen in uncomplicated preeclampsia and eclampsia. They are more

characteristic of chronic cardiovascular and renal diseases. Nerve fiber layer

infarcts and vitreous hemorrhage secondary to neovascularization are also common.

Despite this, most changes are reversible once preeclampsia resolves. Serous

exudative retinal detachments may occur in severe preeclampsia or eclampsia.

They tend to be bilateral, bullous, and associated with preeclampsia

retinopathy changes. The underlying mechanism is most likely related to

choroidal nonperfusion and resultant subretinal leakage. Most patients with

serous detachments have resolution of symptoms within weeks after delivery.

Cortical blindness,

although a rare complication, has been reported to cause vision loss in

preeclampsia secondary to cerebral edema. This may result from vasospasm

causing transient ischemia producing cytotoxic edema. It is also possible that

preeclampsia causes increased

permeability from circulatory dysregulation, thus providing vasogenic edema.

Resolution of the changes associated with preeclampsia and the resultant

cerebral edema usually result in visual recovery.

In benign essential hypertension, examination of the eye grounds reveals a different picture. The retinal arterioles are more narrowed and tortuous, and they present the aspect of silver or copper wire. Arteriovenous nicking is very frequent in essential hypertension and rarely seen in preeclampsia. Fresh and old exudates can be seen distributed in the retinal field, resembling cotton wool. In essential hypertension, hemorrhages are not frequently seen. In malignant hypertension and in chronic kidney diseases, besides the arteriolar changes described above, a great number of fresh and old exudates can be observed together with patches of old and fresh hemorrhages. Choking of the disk is so marked in these cardiovascular and renal conditions that delineation of its contours may become very difficult.