Pediatrics:

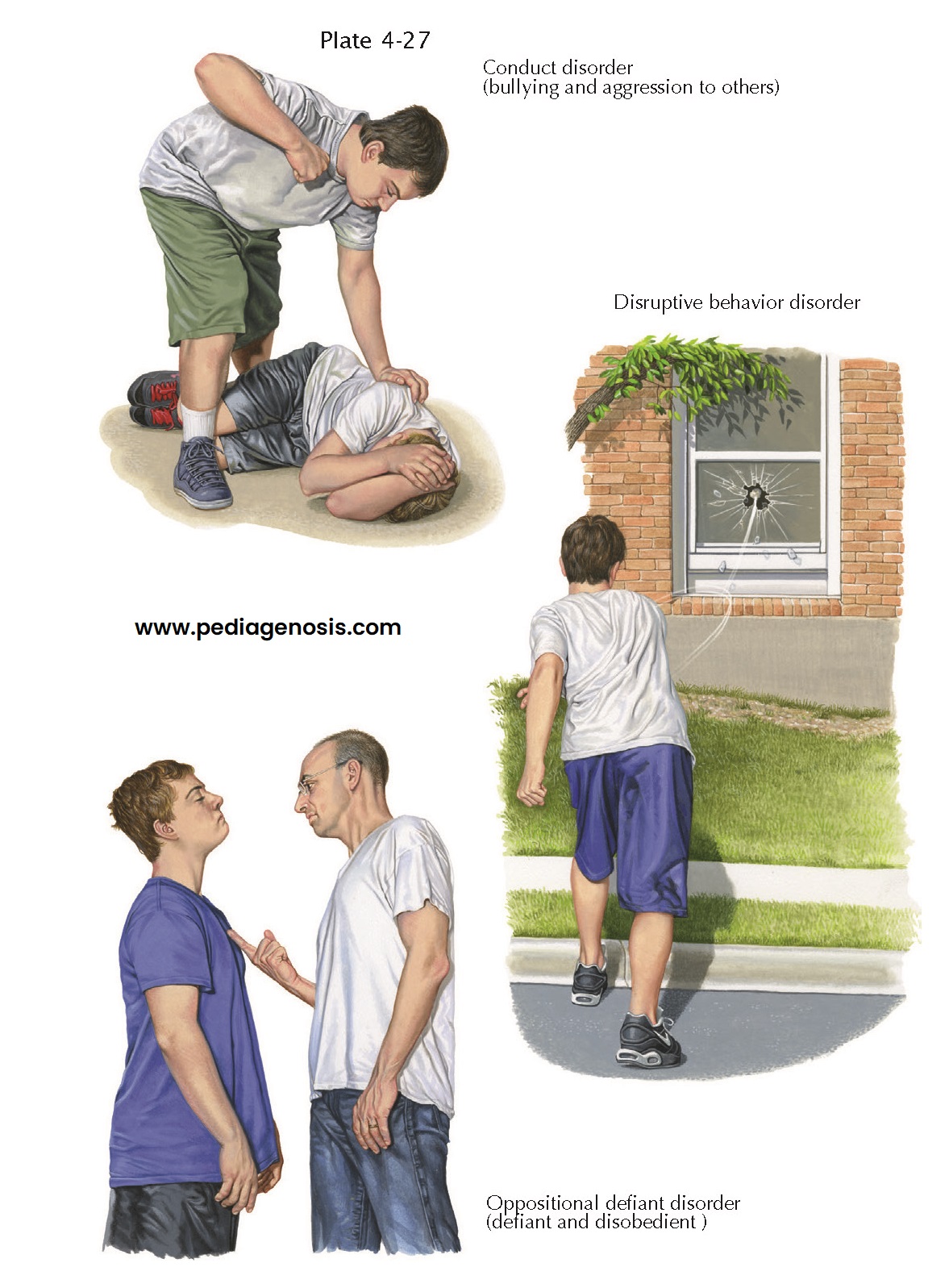

Disruptive Behavior Disorders

The disruptive behavior disorders (DBDs) are

mental health problems occurring in children and adolescents, more commonly in

boys, characterized by out-of-control behavior. Prevalence rates vary from 1%

to 16%. A cluster of factors, including the child’s characteristics, parental

interactions, and environmental factors contribute to their development.

Ineffective parenting strategies often underlie these disorders. Parents may have insufficient time and emotional energy for the child or may use inconsistent methods of disciplining and limit setting. These ineffective strategies include authoritarian parenting, wherein the parent demonstrates too much anger or is too harsh, and permissive parenting, with the parent giving in to the child’s excessive demands. Authoritative parenting is defined as having high levels of both warmth and firmness and is the most effective parenting strategy.

The DBD child may be

strong-willed because of genetically inherited personality characteristics,

certain intrauterine exposures (such as cigarette smoking), lack of positive

parental attachment, because of stress, or a lack of predictable structure in

the home or com- munity environment. Disruptive behavior disorders are more common

in families with serious marital discord, families of low socioeconomic status

and in neighborhoods characterized by high crime rates and social

disorganization.

Oppositional

Defiant Disorder. Oppositional

defiant disorder is the less severe. It is characterized by a recurrent pattern

of negativistic, defiant, disobedient, and hostile behavior, such as

deliberately annoying others, frequent arguments, and angry outbursts directed

toward authority figures, that is, parents and teachers. To confirm the diagnosis,

these behaviors must be more frequent and more severe than normal children

exhibit, present at least 6 months and impair the youth’s function at home, at

school, or with peers.

The more serious DBD—conduct

disorder—is characterized by a persistent pattern of serious rule-violating

behavior, including instances that harm or have the potential to harm others.

Physical aggression to people and animals, destruction of property, lying or

stealing, running away from home, and truancy are typical examples. Boys are

more likely to have conduct disorder compared with oppositional defiant

disorder. Rather than physical aggression, girls are more prone to use verbal

attacks, ostracism, or character defamation. To confirm this diagnosis, DBDs

must be present at least 1 year, impairing the youth’s home, school, and/or

peer function.

Diagnosis. DBDs are most accurately diagnosed by

child and adolescent psychiatrists, child psychologists, child-trained social

workers, and clinical nurse specialists. The evaluation requires input from

multiple individuals who know the child. The diagnosis is based upon findings

from interviews and a mental status examination. There are no specific

diagnostic imaging studies, blood tests, or other medical tests that are

diagnostic.

Treatment. The best therapy for oppositional

defiant disorder is helping the parent learn effective parenting strategies.

Treatment goals include helping the youngster become more cooperative and less

argumentative or destructive. It is very useful to ascertain the child’s and

family’s strengths and build on them in addition to focusing on their problems.

Behavior modification strategies

include developing a warm, loving relationship between parent and child;

providing a predictable, structured environment; setting clear and simple

house-hold rules; consistently praising and rewarding positive behaviors (such

as completing chores or homework); consistently ignoring annoying behaviors

(such as whining or arguing), followed by praise when the annoying behavior

ceases; and consistently outlining potential consequences (such as loss of

privileges) for dangerous or destructive behaviors. Social-emotional skills

training for the child, helps them develop skills to identify and manage

feelings, get along with others, and make good decisions based on thinking

rather than feeling.

Because conduct disorder

is an extremely serious condition, treatment must be more intensive and extensive, sometimes involving other

child-serving agencies (i.e., juvenile justice and child welfare). Treatment is

likely to be effective when administered early in the course of the disorder

before maladaptive behaviors become more entrenched. If physically aggressive

behavior is prominent in conduct disorder, medications (including atypical antipsychotics)

can be helpful.

Course. Oppositional defiant disorder, and to a lesser extent, conduct disorder respond well to the above treatments when delivered by qualified mental health professionals. Although some children grow out of the DBDs, if untreated, these disorders can go on to cause significant problems, including difficult relationships with parents and other adults, failure at school and delinquency, and in adulthood, antisocial or criminal behavior.