Parasomnias

Parasomnias are characterized by certain unusual or unwanted movements or behaviors that occur during nighttime sleep.

Typically, the patient experiences repeated very brief episodic leg movements ranging from simple great toe dorsiflexion to violent flexion of the entire lower extremity. This may recur at regular intervals, up to several times per minute, all night long. If the movements are mild, neither the individual patient nor the bed partner may recognize the PLMs. On the other hand, if more violent, the movements may awaken the patient, bed partner, or both. Although mild PLMS may not be associated with arousals and are of no clinical significance, in some patients the more pronounced PLMS may cause repeated arousals. As a result, the patient may develop, daytime sleepiness. PLMs can often be treated successfully with dopamine agonists, such as ropinirole or pramipexole, or with benzodiazepines, such as clonazepam.

RLS often

occurs in the same patients as those who have PLMs, although there is another

group of RLS patients who do not get PLMs. The patient with RLS perceives an

irresistible urge to move the legs, especially while sitting or lying down;

these feelings are relieved when the patient stands or walks. The patient often

describes the feeling as an uncomfortable sensation in the legs that is only

relieved by leg movement. Many RLS patients demonstrate iron deficiency or low

ferritin levels, and in those patients treatment with iron may help. In

addition, the symptoms of RLS may be successfully treated with dopamine

agonists, benzodiazepines, or opioid drugs. Antidepressants and stimulants may

exacerbate RLS and PLMS. Two genome-wide screening studies have identified a

genetic polymorphism that correlates with RLS with PLMs, suggesting that many

cases may have a heritable cause.

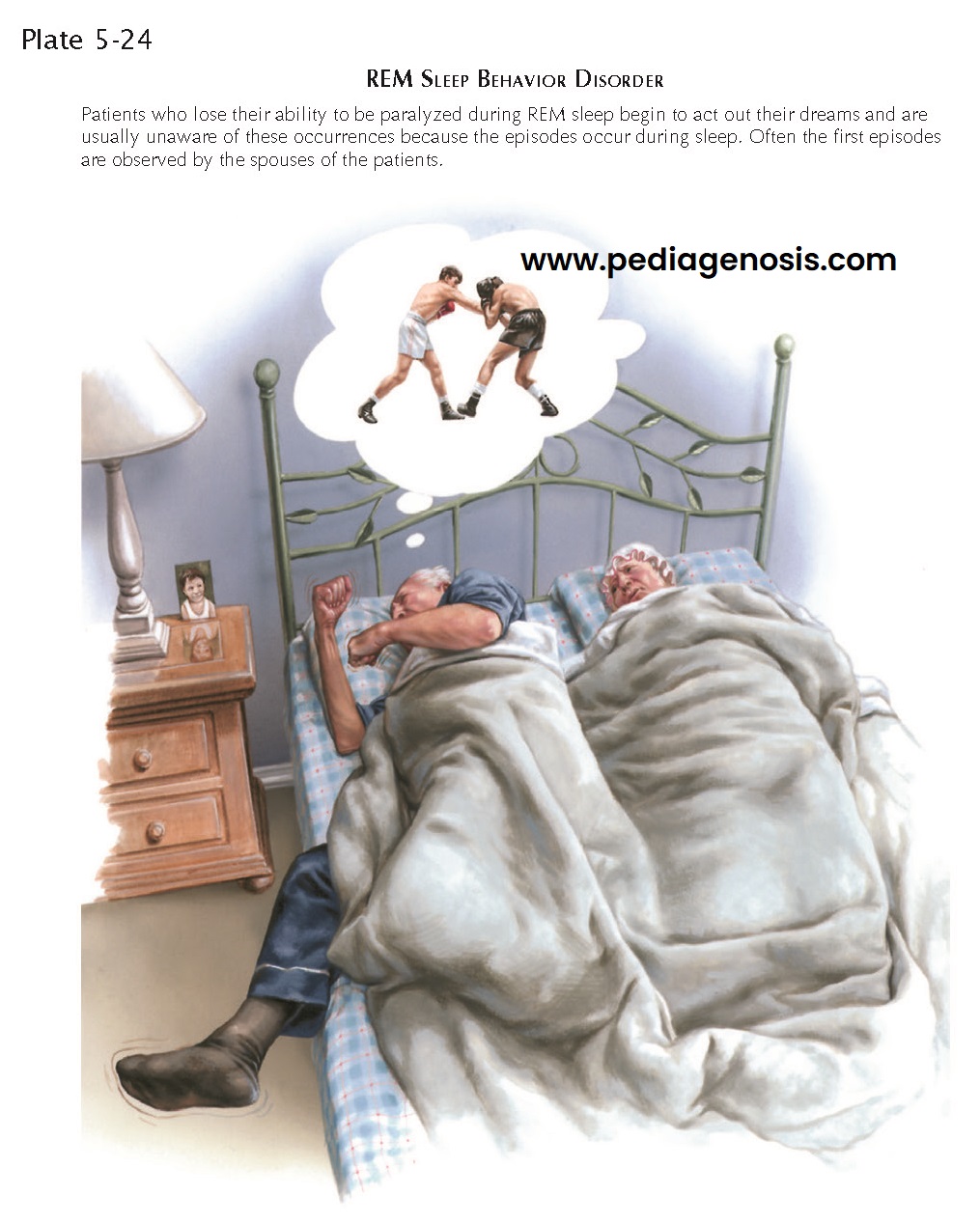

Patients with

REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) exhibit complex motor activity during REM

sleep. During REM sleep, when active dreaming occurs, there is activation of

reticulospinal pathways that result in profound inhibition of motor neurons,

resulting in deep paralysis of voluntary muscles in intact individuals. In

patients with RBD, this paralysis breaks down and there are intermittent jerky

movements and sometimes complex behaviors during REM sleep. In many respects,

RBD is the opposite of the cataplexy attacks seen in patients with narcolepsy,

who have activation of the REM sleep paralysis system while awake. RBD patients

typically appear to be fighting off attackers and report dreams that match

their actions. However, as with PLMS, patients with RBD are often unaware of

these occurrences, unless they are reported by a bed partner, or the patient falls out of

bed and is injured during a foray. RBD is usually treatable with either

clonazepam or melatonin. However, in severe cases, the bed partner may have to

sleep in a different room and the mattress must be placed on the floor, the

furniture removed, and windows boarded over to prevent the patient from injuring

himself or his bed partner during an attack. Some patients use large straps

across the bed to avoid such excursions. Most patients with idiopathic RBD (no

other predisposing cause) are men, and the peak onset is in the fifties or

sixties. Recent studies show that most patients with idiopathic RBD

subsequently develop a synucleinopathy, usually Parkinson disease or diffuse Lewy

body dementia, but occasionally multiple systems atrophy. However, the time to

diagnosis of these neurodegenerative disorders may be quite prolonged, with

about half the patients with RBD developing a synucleinopathy within 12 years,

and almost 80% by 20 years. In one case report the patient was found by his new

bride to have RBD on his wedding night at age 21 and did not develop Parkinson

disease until age 71. Other risk factors include the use of antidepressants

that prevent reuptake of serotonin or norepinephrine. Again, this situation

represents the opposite of cataplexy, the development of REM atonia during

waking in narcoleptic patients, where these antidepressants suppress the

attacks.

NIGHT

TERRORS, SLEEP WALKING, AND BED WETTING

These disorders

commonly occur in children and rarely persist into adult life. As a group,

these childhood parasomnias tend to occur during the deepest stage of slow-wave

sleep and tend to become more brief and less profound during adulthood.

Typically, the patient with night terrors suddenly sits up in bed, has dilated

pupils, a frightened expression, and a rapid pulse. Occasionally, the affected

individual may suddenly dash from the bed with such vigor that he or she may

sustain an injury. Often, the child returns to sleep without any memory of the

event. If awakened during the night terror, the child describes a frightened

feeling or image but not a complex dream. Although there are no known adverse

outcomes to night terrors, they can be quite frightening to parents, and it is

important to distinguish them from other, more rare nocturnal events, such as

seizures.

Sleep

walking, or

somnambulism, also tends to occur in children during deep slow-wave

sleep. The child may walk and talk, but the speech is typically mumbled and

incoherent. The patient can generally be led back to bed and will not remember

the incident the following day. Often, an explanation of the problem to the

family is sufficient.

Enuresis, or bed wetting, typically

occurs in this same age range and also during the deepest part of slow-wave

sleep. In general the patient is not aware of the event, awakening in damp bed

clothing.

All of these childhood parasomnias frequently respond to drugs that reduce the tendency to fall into deep slow-wave slee , such as tricyclic antidepressants or benzodiazepines.