OBSTETRIC

LACERATIONS I—VAGINA, PERINEUM, VULVA

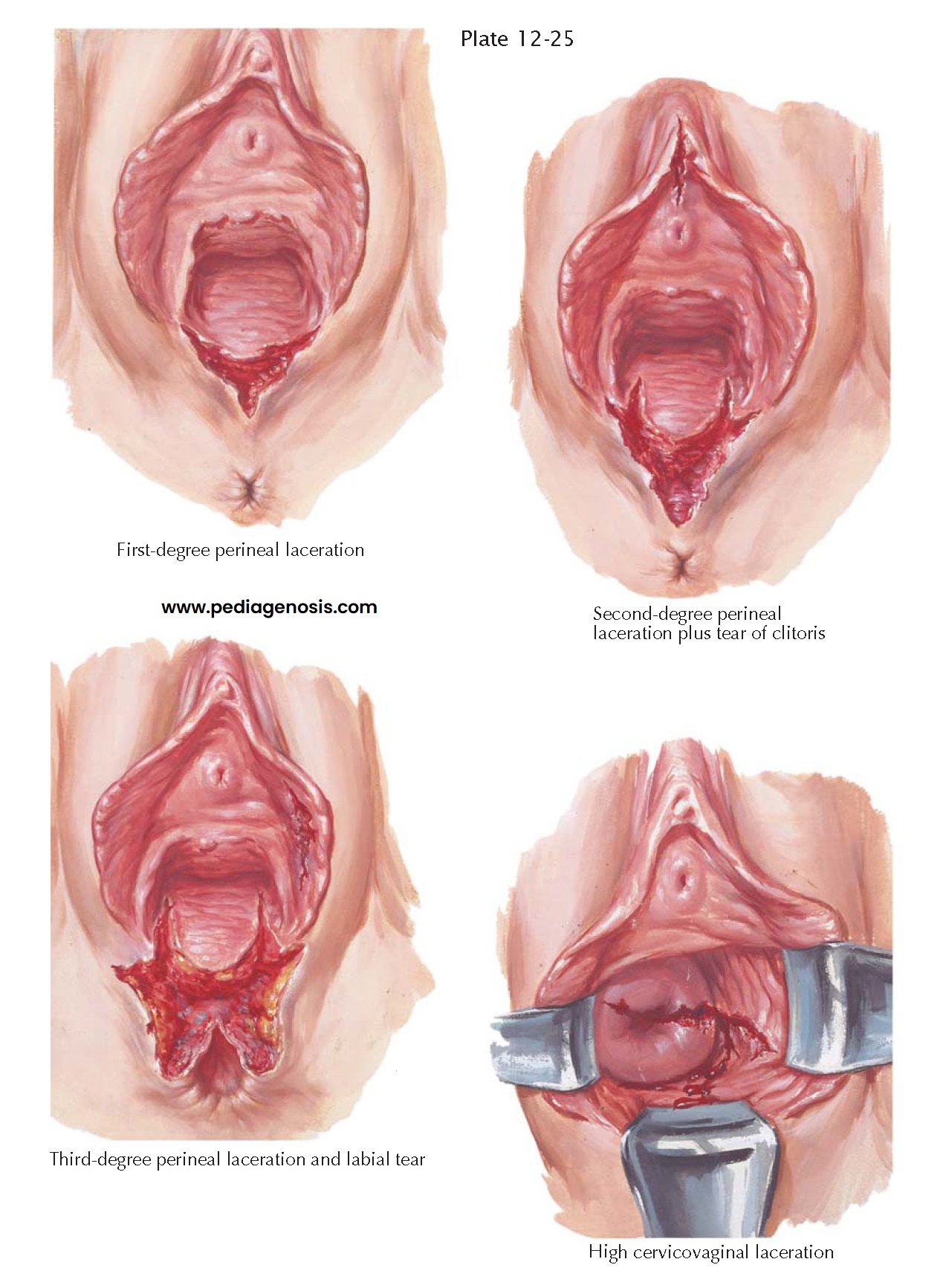

Nearly every primiparous birth results in at

least a minor injury to the soft parts of the vagina, perineum, and vulva.

Traditionally a timely median or mediolateral episiotomy was believed to reduce

the likelihood that such tears will be extensive, but the role of routine

episiotomy has come under question. In spite of prophylactic incisions, bad

lacerations occur, which vary greatly in degree and direction. The simplest

type is a first-degree perineal laceration that extends posteriorly toward the

anus through the vaginal epithelium and perineal skin. Occasionally, the

inferior borders of the labia are also torn, and lateral retraction from the

cut surface causes gaping of the wound. Bleeding may be brisk, but

self-limited, although no vital structures have been damaged. It is important

to make a thorough examination of the adjacent tissues to rule out the presence

of occult damage elsewhere.

Second-degree lacerations involve the skin, vaginal epithelium, and the superficial muscles of the perineum but not the fibers of the external anal sphincter. They often extend upward along the sides of the vagina, producing a triangular defect because of retraction of the superficial perineal muscles. At the lower margin of a second-degree tear, the capsule of the external anal sphincter bulges upward into the wound. Concomitant lacerations of the anterior vagina, clitoris, prepuce, urethra, and labia are frequently present.

A third-degree perineal

laceration is a far more serious injury because of the threat of future

interference with normal bowel function. In this instance, the skin, vaginal

epithelium, and perineal body are torn, and the external anal sphincter is

ruptured anteriorly with retraction of its severed ends. Although the perineum

receives the main expulsive force and is there- fore more often lacerated, the

incidence of damage to the anterior wall increases proportionately. Superficial

epithelial wounds, perforation of the bladder, or even avulsion of the urethra

may result.

A tear that includes the

rectal mucosa or extends up the anterior rectal wall to compromise the internal

sphincter is referred to as a fourth-degree laceration. Third- and

fourth-degree lacerations commonly produce fecal incontinence if untreated and

are slow to heal. The puckered scar tissue, which forms in wounds that heal by

second intention in this area, is often painful.

Inspection of the cervix

and upper vagina after delivery, regardless of the presence or absence of

external wounds, should always be considered. Cervical lacerations originating

at this time may be the source of problems, including postpartum bleeding and

cervical insufficiency. If the tear extends to the vaginal fornices, as it often

may, the end result may be dyspareunia or urinary incontinence due to downward

pull on the internal vesical sphincter. More acute symptoms are hemorrhage,

hematoma, or infection followed by purulent leukorrhea.

The early and late clinical manifestations of all these injuries serve to emphasize the necessity of instituting prompt surgical treatment. Transfusions may be necessary to combat hemorrhage and shock if bleeding is significant. Sutures should be carefully and economically placed, which, in the difficult cases, usually requires the services of an assistant for adequate exposure. Upon completion of the third stage of labor, all lacerations should be repaired. In the case of third-and fourth-degree lacerations, this means that the severed fibers of the rectal sphincters are reunited and further strengthened by reapproximation with either an end-to-end or overlapping technique. To provide additional support, plication of the levator muscles in the rectovaginal space has been advocated in the past. Such repair may be done safely immediately following delivery, though data on the advisability or success of such an approach is lacking. Primary repair is always preferable because, in the event of failure, subsequent corrective procedures offer a much more limited prognosis.