NEUROPATHWAYS

IN PARTURITION

Control of pain during labor and delivery has

become a major factor in obstetric practice, and pain has become a key element

of assessment (vital sign) for all hospitalized patients. It is thus important

to have an under-standing of the topographic location and specialized

functions of the neuroafferent pathways to all organs and structures involved

in birth. The obstetrician often is faced with a need to maintain the uterine

activity or to plan a coordinated augmentation of the expulsive forces in which

the striated abdominal and intercostal muscles are involved, including the

diaphragm.

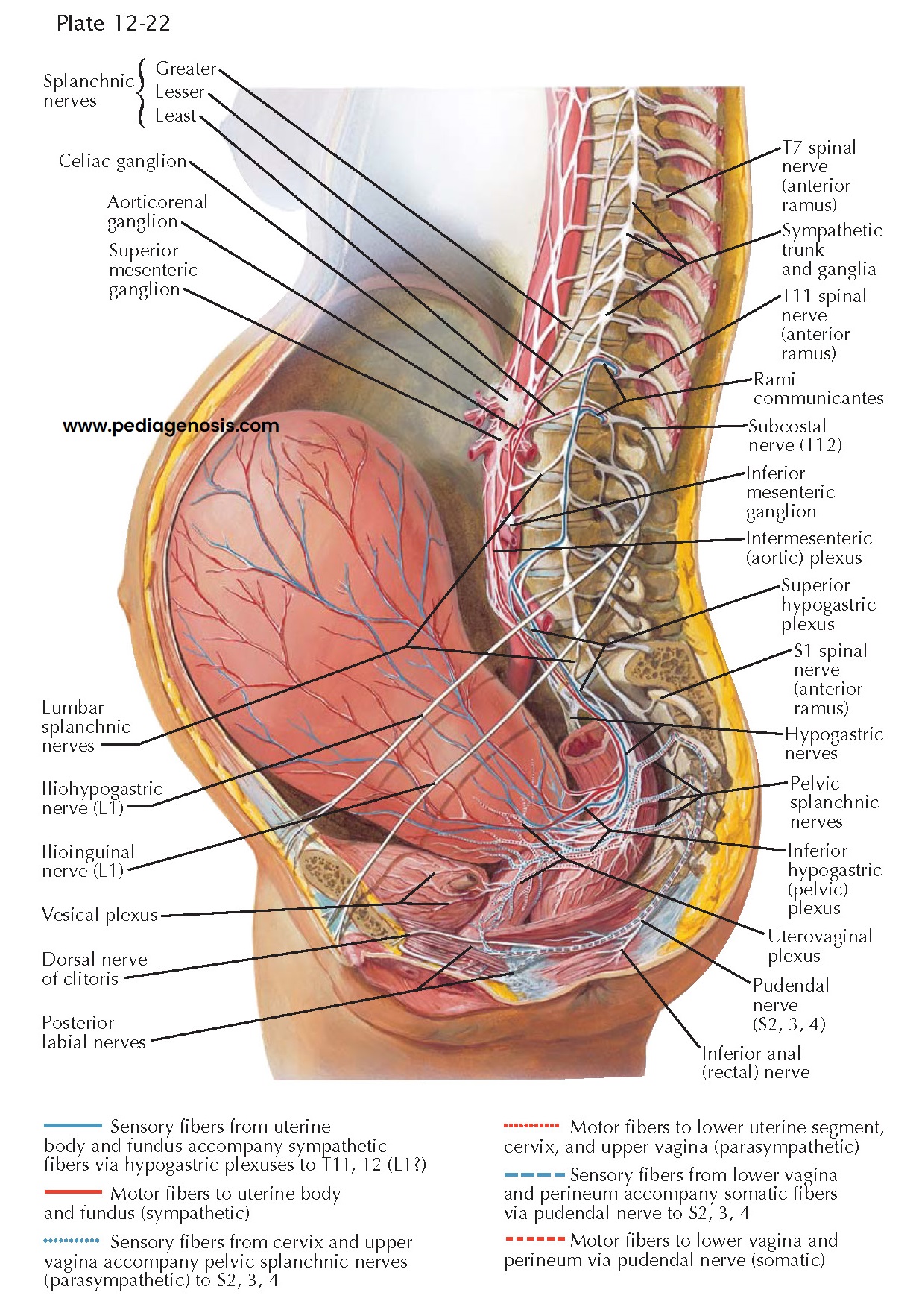

The pain of labor is characterized as rhythmically increasing and fading pain that occurs synchronously with uterine contractions, coming every 3 to 4 minutes and lasting 30 to 40 seconds but may occur more often. This pain is transmitted first over the sensory fibers from the corpus and fundus of the uterus (blue solid lines) to the large circumcervical ganglionic network (Frankenhäuser), and thence over the hypogastric nerves and the lower aortic postganglionic sympathetic fibers to the paravertebral sympathetic chain at the level of the second and third lumbar vertebrae. Continuing without synapse in a cephalic direction, these nerves traverse the gray rami of the 11th and 12th thoracic and probably also the 1st lumbar nerve to enter the communicating system of these three dorsal root ganglia with the preganglionic afferent system in the lateral spinothalamic fasciculus of the spinal cord to the thalamic pain center and its cortical radiations. Whenever these pathways are interrupted by 11th and 12th paravertebral segmental block, by epidural 11th thoracic through 1st lumbar block, by ascending caudal block or by saddle spinal block anesthesia, the labor contraction pain is alleviated.

The second component of

labor pain is the backache associated with cervical dilation. These stimuli are

transmitted through the parasympathetic system of the second, third, and fourth

sacral nerves (blue dotted lines). The resulting sensation of sacral and

sacroiliac has been interpreted as pain over the skin and fascia distribution

of the somatic segmental branches of these nerves. Low saddle or spinal block,

as well as the infrequently used caudal block, will relieve this pain.

The third component of

childbirth pain is that trans- mitted from the stimulus of stretching the lower

birth canal and the perineum. Pressure upon the bladder and rectum through the

pudendal nerve or its perineal and hemorrhoidal branches may also be involved.

This pain can be relieved by pudendal and perineal nerve block, anesthetizing

the nerves indicated in the picture by the broken lines. These blocks, of

course, also produce a flaccid paralysis of the perineal musculature, which,

however, greatly facilitates operative or obstetric maneuvers and provides analgesia for any

reparative procedures that may be required following delivery.

Epidural anesthesia is

commonly used for childbirth in the United States because it provides good

analgesia with a wide margin of safety. Fewer than 1 of 100 women may

experience a headache following an epidural. Use of epidural anesthesia may be

associated with reduced contraction frequency or strength, or an impaired

ability to push as effectively, so interventions such as oxytocin or operative

delivery may become necessary.

Successful saddle or spinal anesthesia produces a more or less complete analgesia from the perineum and sacral plexus ascending to the 10th thoracic segment. The more heavily myelinated nerves of the lower abdominal musculature and, depending on the position of the patient and the timing of repositioning after injection of the anesthetic, the entire anterior roots continue to function and permit intentional cooperation of the individual by increasing the intraabdominal pressure required for pushing during delivery.