MENISCAL VARIATIONS AND TEARS

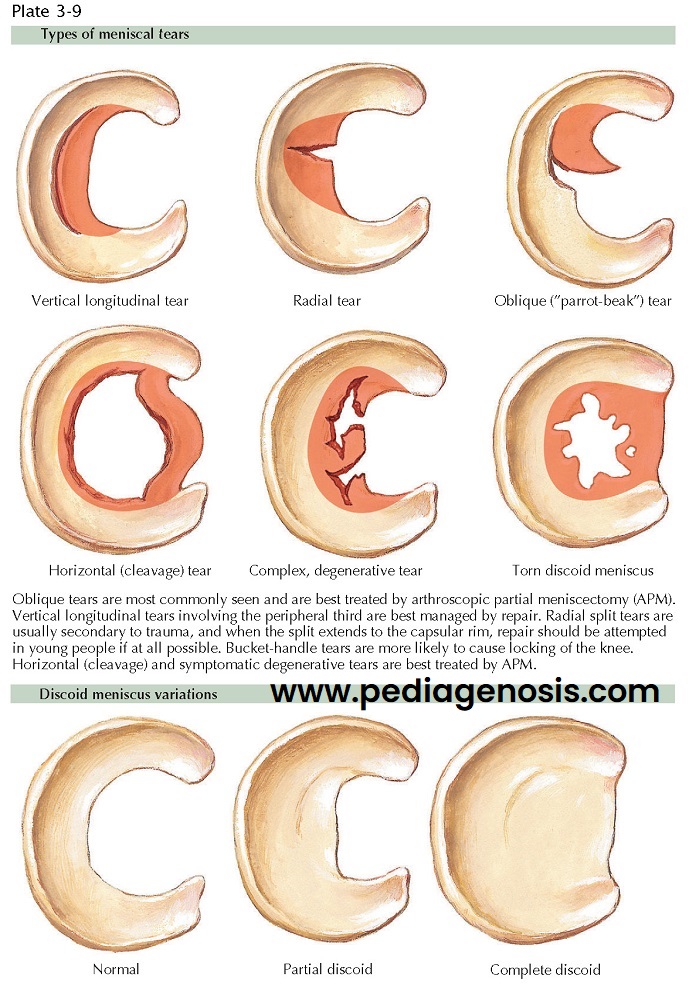

TYPES OF MENISCAL TEARS AND DISCOID MENISCUS VARIATIONS

The meniscus is normally a crescentic structure, although several forms of discoid lateral menisci have been described. These range from a complete disc to a very rare ring-shaped meniscus with abnormal thickness. The common explanation for these variant discoid forms assumes that the normal meniscus is formed from an original discoid shape and that the discoid lateral meniscus is a congenital variant in which the central portion does not degenerate with time. This theory would explain the variously shaped menisci found at surgery. However, no discoid menisci have been found in fetuses and a review of comparative anatomy shows no mammal with such a pattern of formation.

A second theory is a developmental one. Many discoid

lateral menisci have abnormal attachments to the tibia. When the attachment to

the posterior tibial plateau is deficient, there is a strong attachment to the

medial femoral condyle by the meniscofemoral ligament (Wrisberg’s ligament).

This pattern of attachment may allow abnormal movement of the lateral meniscus:

the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus moves into the center of the lateral

compartment during full extension of the knee. With time, scarring and fibrosis

of the lateral meniscus occur, with resultant thickening. These changes may

account for the popping on flexion and extension that is usually noticed during

childhood or early adolescence.

Treatment. Many discoid

menisci are asymptomatic, and the mere presence of one is not an indication for

treatment. The popping itself is not harmful unless it is accompanied by pain

of swelling of the knee. Pain, swelling, and a history of trauma are relative

indications for arthroscopy. Tears of the meniscus or degenerative changes on the articular surfaces may necessitate

resection. Arthroscopic techniques allow for partial resection or saucerization

of the discoid lateral meniscus, leaving a peripheral rim that may function

properly. Resection may be difficult because of the increased thickness in such

menisci. Prognosis for patients with discoid menisci is good. Discoid menisci

without degenerative changes have been found in the joints of elderly persons.

Therefore, every attempt should be made to salvage function of the meniscus by avoiding complete excision simply to

eliminate the snapping, clicking sensation.

MENISCUS TEARS

Tears of the meniscus are common findings in a patient

with an acutely injured knee, especially in situations in which a traumatic

twisting event has occurred. Tears may occur in either meniscus or in both menisci

at the same time. A meniscus

tear often becomes symptomatic if its torn portion is mobile and slides into an

abnormal position between the articular surfaces of the femur and tibia.

Patients with a displaced meniscus tear often report pain at the joint line and

blocked extension, flexion, or both. The affected knee frequently gives way and

exhibits recurrent effusions.

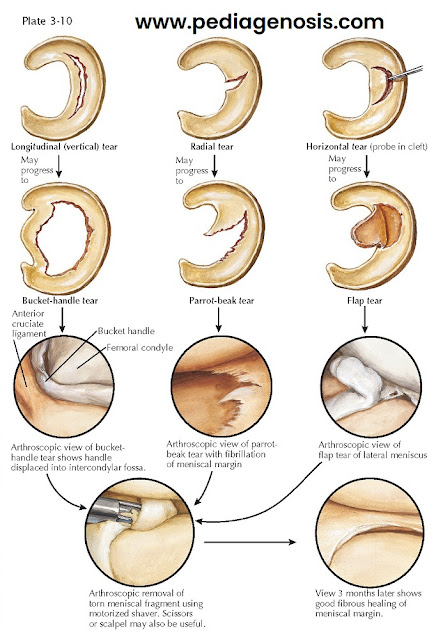

A bucket-handle tear is a longitudinal tear through

the substance of the meniscus. The torn portion remains attached to the

anterior and posterior horns of the meniscus. A small radial tear initially

causes very few symptoms, but if not treated it may progress to a deeper, more

symptomatic parrot-beak tear. The unstable flap of meniscus may cause

mechanical signs in the injured knee such as recurrent effusions, giving way,

and a catching sensation. Horizontal tears of the meniscus appear to be a

delamination of the substance of the meniscus. Neglected horizontal tears

frequently result in an unstable flap of meniscal tissue, which can also cause

mechanical signs.

When an unstable portion of meniscus displaces into

the intercondylar notch and becomes incarcerated, it will cause the knee to

lock. Manipulation of the knee may be possible and often occurs with a loud,

audible and palpable “clunk.” This sound and the temporary resolution of

symptoms indicate reduction of the displaced portion into its normal anatomic

position. A persistently locked knee requires urgent intervention. If it is

neglected, attempts at weight bearing and knee movement cause severe,

irreversible erosion of the articular cartilage surfaces of the femur and

tibia.

Physical Examination and Special Tests

·

Joint line tenderness:

Tenderness along the medial or lateral joint lines is

among the most sensitive findings for a meniscal tear.

· McMurray test: The patient is supine and relaxed. The patient is asked to flex the knee

maximally with external tibial rotation (medial meniscus) or internal tibial

rotation (lateral meniscus). While maintaining rotation, the patient brings the

knee into full extension. A positive test is indicated by a painful pop

occurring over the medial joint line (medial meniscus) or lateral joint line

(lateral meniscus).

· Apley compression

test: The patient is prone. The knee is flexed to 90 degrees

with external tibial rotation (medial meniscus) or internal tibial rotation

(lateral meniscus). Axial compression is applied to the tibia while the patient

flexes and extends the knee. A positive test is indicated by a painful pop over

the medial joint line (medial meniscus) or lateral joint line (lateral meniscus).

McMurray and Apley test results may vary considerably from one examination session to the next owing to patient apprehension and

chronicity of injury. A joint effusion will often be present after an acute

tear. Chronically, atrophy of the quadriceps muscle may occur. With peripheral

meniscus detachment and positive anterior drawer test, a loud “clunk” may be

elicited as the meniscus displaces during anterior drawer testing. Imaging.

Plain films are usually normal, unless a meniscus tear has been present

for a significant time. After that time, they may show joint line spurring,

narrowing, or other arthritic changes. MRIs have now supplanted arthrograms

for diagnosis of meniscal injury. MRI has a sensitivity as high as 95% for

demonstration of medial meniscus tears but has somewhat less sensitivity in

detection of lateral meniscus tears.

Treatment. In young,

active persons, arthroscopic repair of torn menisci should always be considered.

In these younger patients the loss of a large portion of a meniscus can be

devastating because meniscal deficiency can lead to earlier-onset arthritis

and, potentially, total joint arthroplasty.

At the time of the surgery, with the patient under

anesthesia, a locked knee may spontaneously unlock. The knee is then examined

manually to determine any ligament instability, and an arthroscopic examination

is performed. To help preserve the articular cartilage, the displaced part of

the meniscus can be removed during arthroscopy.

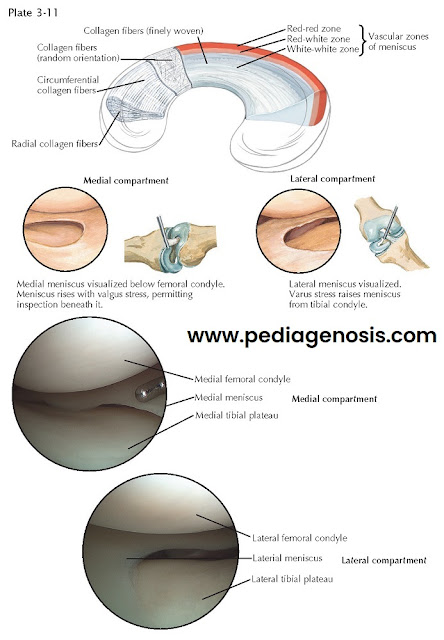

Repairs in the well-vascularized peripheral third

(“red zone”) of the medial and lateral menisci have been quite successful. With

proper technique and stabilization of the knee joint with ligament repair where necessary, repair of the meniscus can be successful in

90% of cases. Multiple studies have looked at establishing which tears outside

the vascular peripheral third can be repaired and whether there are biologic or

pharmacologic means that may improve the potential for healing. Although these

tears have less chance of healing, repair may well be indicated in younger

patients. Approaches to repair include all-inside, out-side-in, and inside-out techniques, with most surgeons now preferring the

all-inside approach when possible.

Rehabilitation programs after arthroscopy and partial meniscectomy generally include minimal immobilization of the knee, immediate weight bearing, and early physical therapy. Therapy consists of gait training and active and passive range-of-motion and quadriceps- strengthening exercises. Ice or heat may be applied as needed. After repair of meniscus tears, vigorous rehabilitation and range-of-motion exercises may be delayed a few weeks.