KNEE LIGAMENT INJURY

|

| RUPTURE OF THE ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT |

Ligament injuries (sprains) of the knee are very common in athletes. In first-degree sprains, the ligament is trenched, with little or no tearing. These injuries produce mild point tenderness, slight hemorrhage, and swelling. Erythema may develop over the painful area but resolves in 2 or 3 weeks after injury. Joint laxity is not present, and the injury does not produce any significant long-term disability. Appropriate treatment consists of rest and muscle rehabilitation. Seconddegree sprains are characterized by partial tearing of the ligament, resulting in joint laxity, localized pain, tenderness, and swelling. When stress is placed on a joint during examination, the examiner should still feel a definite “end point” to the joint movement. Because the ligament is only partially injured, the joint remains stable; thus, vigorous rehabilitation alone will likely be sufficient treatment. Third-degree sprains produce complete rupture of a ligament, making the joint unstable. Tenderness, instability, absence of a definite end point to stress testing, and severe ecchymosis are the hallmarks of third-degree sprains. Surgical intervention may be needed.

Sprains of the medial (tibial) collateral ligament are caused by a valgus force to the knee. Patients

frequently report a snapping or tearing sensation and pain on the medial aspect

of the knee. If only the MCL is injured, patients can usually continue to walk

and may be able to continue the activity that causes the injury.

Physical examination reveals tenderness along the

course of the MCL, and careful palpation can isolate the precise level of

injury: at the origin of the ligament, on the medial femoral condyle, at the

joint line (mid-substance), or along the long distal insertion of the ligament

into the medial aspect of the tibia. Patients are more comfortable if examined

lying supine on the examining table with the thigh supported. The physician

cradles the lower leg in both hands off to the side of the table and

alternately applies varus and valgus stresses to

the knee (varus and valgus stress tests). When the leg is fully extended, the

PCL is the structure most responsible for mediolateral stability. However,

placing the knee in 30 degrees of flexion takes the PCL “out of play” so the

MCL can be tested by applying a valgus force.

Third-degree sprains of the MCL may require direct

surgical repair. However, an isolated third-degree sprain may be successfully

treated by controlling swelling, by

increasing range of motion, and with rehabilitation of the quadriceps femoris

and hamstring muscles.

Marked medial (valgus) laxity may indicate that the

posteromedial corner of the knee capsule is also injured. Surgical repair is

needed to prevent residual rotational instability. A football clipping injury

may result in the “unhappy triad” of O’Donoghue, which includes ruptures of the

MCL and the ACL plus a tear of the medial meniscus. However, in the recent literature it has been shown that the

lateral meniscus is more likely to be acutely torn at the time of ACL injury,

whereas the medial meniscus is more often compromised in the chronically

ACL-deficient knee. These injuries often require arthroscopically aided repair

of the ligaments as necessary and repair of the injured meniscus if possible.

|

| LATERAL PIVOT SHIFT TEST FOR ANTEROLATERAL KNEE INSTABILITY |

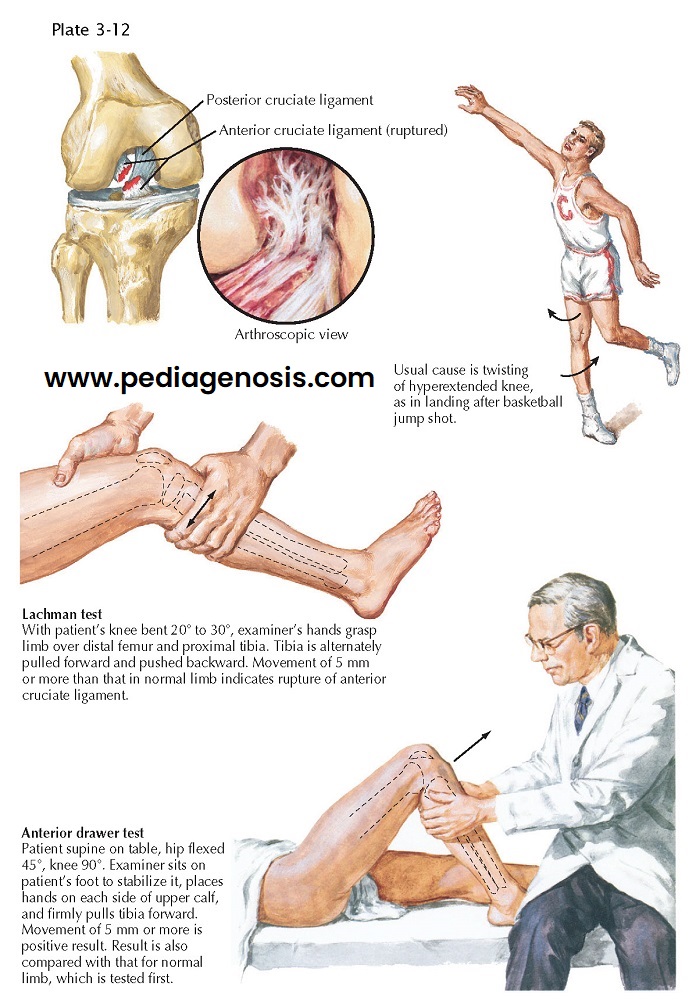

RUPTURE OF THE ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT

The ACL is the primary restraint to anterior

translation of the tibia and it also contributes to internal rotation and

varus/valgus instability with the knee extension. The anatomic configuration of

its two bundles ensures functional tautness throughout the arc of motion, with

the anteromedial bundle taut in flexion and the posterolateral component taut

in extension. Although it may be torn by a contact injury, the ACL is most

commonly injured without contact by a decelerating valgus angulation and

external rotation force. In basketball, the ACL is commonly torn when a player

lands from jumping with the knee in hyperextension and the tibia in internal

rotation. The player hears a “pop,” feels a tear and acute pain in the knee,

and may not be able to continue playing. The knee may feel very unstable during

weight bearing and is often felt as a “giving way” of the knee. Patients

complain that their knee slips or slides when they turn right or left with the

foot planted. This sliding reflects the tibia subluxating anteriorly on the

femur. Rupture of the ACL is a common cause of acute traumatic hemarthrosis.

Physical Examination and Special Tests

·

Lachman test: This test is simple to perform and relatively painless for the patient

with an acute injury. The examiner compares the amount of play in the injured

knee with that in the normal one to deter- mine if abnormal motion is present.

The Lachman test is performed with the knee flexed 20 degrees to reduce the

stability provided by the menisci. One of the examiner’s hands stabilizes the

femur while the other hand grasps the proximal tibia. With the patient relaxed,

the examiner attempts to slide the proximal tibia anteriorly on the femur. An

intact ACL prevents the tibia from sliding forward. When the ligament is injured, the tibia is moved from its

normal position and can be subluxated anteriorly during the test. The examiner

must note the quality of the end point of this stress test. If there is a solid

mechanical stop at the most anterior extent of tibial motion, the ACL may be

only partially torn. However, if the end point is soft and spongy, a complete

rupture should be suspected. The integrity of the PCL must be ascertained before the result of this test can be

considered valid. If the PCL is ruptured, the proximal tibia sags posteriorly,

and the Lachman test will seem to be positive as the posterior subluxation is

reduced.

·

Anterior drawer test: The anterior drawer test is performed with the patient lying supine,

resting comfortably with the knee flexed 90 degrees (see Plate 3-12). The patient’s foot is stabilized during the

test and may be held in place by the seated examiner’s thigh. The examiner

grasps the patient’s calf near the popliteal fossa with both hands and attempts

to slide the tibia anteriorly. When the ACL is ruptured, the tibia slides

anteriorly with respect to the femur. The anterior drawer test is performed

several times, with the patient’s foot and leg positioned first in internal

rotation, then in neutral rotation, and finally in external rotation. As in the

Lachman test, the injured knee must be compared with the normal one. The

anterior drawer test is useful for detecting complete ruptures of the ACL but

is often less sensitive than the Lachman test in diagnosing partial injuries.

· Pivot shift and jerk

tests: These tests identify most cases of clinically

significant knee instability. The patient should be lying supine and relaxed,

although this is often difficult in the acutely injured patient because this

test can reproduce a feeling of discomfort. It has been found that this test is

most accurate when performed on an anesthetized patient. The examiner stands

beside the injured leg, facing it. With one hand grasping the patient’s foot,

the examiner places the other hand on the lateral aspect of the knee, with the

thumb underneath the head of the fibula. With the knee starting in full

extension (pivot shift) or flexed to 90 degrees (jerk test), a valgus force is

applied at the knee while the tibia is internally rotated by the hand holding

the foot. This maneuver causes the lateral tibial plateau to subluxate

anteriorly on the femur. With the knee in extension, the iliotibial tract is

anterior to the instantaneous center of rotation of the knee and acts as an

extensor. The knee is then slowly flexed (pivot shift) or extended (jerk test),

and the subluxation becomes more apparent. At a point between 20 and 40 degrees

of flexion, the iliotibial tract slides posterior to the instantaneous center

of rotation of the knee and acts as a flexor, causing reduction of the tibia.

The reduction is palpable, visible, and frequently audible.

|

| RUPTURE OF CRUCIATE LIGAMENTS: ARTHROSCOPY |

Treatment. Not all acute

injuries of the ACL require surgery. If

the careful physical examination, using anesthesia if necessary, reveals

minimal ligamentous laxity and no sign of meniscus injury and the patient does

not have sensations of instability or symptoms preventing full function, then

prompt, vigorous rehabilitation is instituted. If

the Lachman or anterior drawer test indicates mild ligament instability but the

pivot shift test is negative and there are no other associated injuries, a

nonoperative program may be instituted. However, significant instability may

eventually develop if injury of the ACL is neglected or treated conservatively.

It has been shown that a chronically ACL-deficient knee can also lead to

degenerative tears of the meniscus and eventually an earlier onset of

osteoarthritis. Patients whose knees

give way during daily activities are candidates for delayed reconstruction of

the ligament. If the instability is a problem only during intense physical

activity, using a brace may provide relief.

Physical therapy focuses on rehabilitation of the

quadriceps and hamstring muscles. Although the knee is reasonably stable,

instability may develop gradually, eventually necessitating reconstruction of

the ACL.

Increased instability may lead to meniscus tears.

Surgical

treatment is usually indicated in patients with complete ACL injury,

symptomatic or clinical instability, and a positive pivot shift test. The

procedure used is dictated by the patient’s lifestyle, expectations and other

medical conditions. Older, sedentary patients may need no surgery, whereas

young, active patients should be considered for repair or reconstruction. The

goals of surgery are to restore stability to the knee to permit return to

activity, prolong the survival of the menisci, and delay the development of

osteoarthritis.

Many techniques are used to repair or reconstruct the

ACL, with specific considerations to be taken into account based on each

individual patient. In the skeletally mature patient, the ligament is

traditionally recon-structed using an arthroscopically assisted approach. The

graft choice in younger patients will usually be a hamstrings or bone-patella-bone

autograft, whereas older patients or those with other contraindications to

hamstrings harvest may use allograft tissue. In skeletally immature patients

with open growth plates, there exist multiple modifications to the traditional

reconstruction methods that avoid compromising the tibial, femoral, or both

open physes. Protected weight bearing is allowed immediately, with some

surgeons advocating the use of continuous passive motion machines and braces in

the early postoperative period. Early and consistent physical therapy is

important to achieve optimal results. Patients should avoid participation in

high-demand sports for 6 to 12 months after surgery.

|

| RUPTURE OF POSTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT |

RUPTURE OF POSTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT

The PCL is the chief stabilizer of the knee in full

extension. The most common causes of rupture of this ligament are

hyperextension of the knee and a direct blow to the anterior aspect of the

flexed knee. Severe varus or valgus stress to the knee after injury to the

collateral ligaments can cause rupture of the PCL.

Physical Examination and Special Tests

A knee lacking a functioning PCL may be hyperextended

during examination. The examiner stands at the foot of the supine patient and

simultaneously lifts both feet by the great toes, observing the amount of

extension at each knee. A knee with rupture of a PCL exhibits noticeable

hyperextension and greater joint laxity than its normal counterpart when varus

and valgus stresses are applied

with the knee in full extension.

· Posterior drawer test:

The posterior drawer test is per- formed with the

patient lying supine on an examining table and the knee in 90 degrees of

flexion. The patient’s foot is stabilized by the examiner’s thigh on the table

as for the anterior drawer test. The examiner uses

both hands to push the proximal tibia posteriorly in an effort to displace it

relative to the distal femur. By alternately pushing and pulling the tibia, the

examiner can determine if the ACL is intact and if the proximal tibia is moving

posteriorly. The examiner must recognize the starting point of the drawer test

to determine accurately which of the two cruciate ligaments is injured.

· Posterior sag sign: With the patient supine and relaxed, a pad is placed under the distal

thigh on the affected side; the heel is allowed to rest on the examining table,

and the calf of the leg hangs unsupported. The examiner observes the knee from

the patient’s side. When a rupture of the PCL is present, the proximal tibia

subluxates posteriorly and the anterior surface of the proximal leg appears to sag.

Treatment. Patients who have

high-demand knee and severe instability are candidates for reconstruction of

the PCL. This is routinely accomplished in an arthroscopically assisted fashion

as with the ACL, with surgical options again being individualized to each

patient. As with the ACL, when avulsion of the bony attachment of the PCL

occurs at either end, primary repair of the avulsion fragment may be performed.

If bone-to-bone repair is not possible, many surgeons may elect to treat the

patient without resorting to surgery. Repairs of the PCL have historically been

less successful than those of the ACL, with higher risk of recurrent

instability after surgery and loss of motion. Injury to the posterolateral

corner of the knee capsule must also be considered and addressed when necessary

at the time of surgery to avoid a poor functional result.

After surgery, the knee may be immobilized in

extension for a period of 2 weeks. Vigorous physical therapy is then instituted

while avoiding activities that place a load on the knee when it is flexed past

90 degrees. Achieving full extension may be very difficult and should be a goal

of therapy, although manipulation under anesthesia may eventually be required.

|

| PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE LEG AND KNEE |

MEDIAL (TIBIAL) COLLATERAL LIGAMENT INJURY

Injury to the taut MCL is often caused by a valgus

force applied to the knee with external tibial rotation. This may occur by a

noncontact twist event or from a blow to the lateral side of the joint. The

patient will initially describe pain on the medial side of the knee and, with a

complete tear, complaints of the knee giving way into valgus.

Physical Examination. Injury to the

MCL is noted with a positive valgus stress test with the knee in 30 degrees of

flexion as compared with the opposite knee. An injured MCL along with disrupted

ACL or PCL will result in more gapping that occurs when the knee is tested in

full extension. Frequently, but not always, a positive anterior drawer sign

results with external rotation of the tibia as the medial tibial condyle

rotates anteriorly.

Imaging. An abduction

stress film may be used to distinguish ligament injury from epiphyseal fracture

in skeletally immature athletes as a fracture opens at a growth plate and a

ligament tear opens at a joint line. This should be done in 30 degrees of knee

flexion. MRI is also useful to help

to diagnose disruptions or edema in the MCL.

Treatment. Grades I and

II sprains are often treated with the RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation)

protocol, along with use of crutches while weight bearing and physical

rehabilitation. Complete tears, unless present with other associated injuries

or in a high-demand athlete, are rarely surgically repaired. Surgical options include primary repair, allograft

reconstruction, and repair with anchor fixation for avulsion injuries. When

attempting nonoperative treatment, immobilization should be used for a short

period after acute injury with an unstable knee. However, in patients with only

mild instability, rigid immobilization may not be necessary. The patient should begin a rehabilitation program as soon as possible.

|

| SPRAINS OF KNEE LIGAMENTS |

LATERAL LIGAMENT AND POSTEROLATERAL CORNER INJURIES

Injury to the lateral (fibular) collateral ligament

(LCL) often occurs with a varus force or twisting moment at the knee. Injuries

to this region of the knee may be associated with injuries to the popliteus

tendon, iliotibial band, popliteofemoral ligament, and peroneal nerve.

Posterolateral ligaments are often injured by a hyperextension mechanism,

frequently with a blow to the anteromedial tibia.

Patients will complain of pain present over the

lateral ligament complex. The knee may also give way when twisting, cutting, or

pivoting. In chronic cases, posterolateral corner injury gives a feeling of

giving way into hyperextension when standing, walking, or running backward.

Physical Examination and Special Tests

In acute cases, there may be increased gapping on a

varus stress test at 30 degrees of flexion and a positive posterolateral drawer

sign. Chronic cases often show a positive reverse pivot shift and external

rotation recurvatum test. The dial test will likely present in all cases of

severe posterolateral ligament disruption.

· Dial test: With the patient either prone or supine, the examiner will place an

external rotation force to the knee through the ankle at 30 degrees of knee

flexion. Increased external rotation of 10 to 15 degrees as compared with the

opposite knee indicates an injury to the posterolateral corner. If positive,

the test is repeated at 90 degrees of knee flexion, and increased external

rotation at this point indicates a concurrent PCL injury.

·

External rotation

recurvatum test: With the patient

supine and a stabilizing downward force placed on the femur, the externally

rotated foot is lifted by the great toe. Increased recurvatum or hyperextension

at the knee indicates an injury to the posterolateral corner. The external

rotation recurvatum test may also be apparent on standing, giving an increased

varus appearance to the knee.

Imaging. On plain

radiographs, a “lateral capsular sign” shows avulsion of the midportion of the

lateral capsular ligament with a small fragment of proximal lateral tibia. This

is associated with a high incidence of an ACL tear and indicates anterolateral

instability. The “arcuate sign” shows avulsion of the proximal fibula with the

posterolateral ligament and is also associated with an ACL injury. As with MCL

injuries, stress view radiographs

and MRI may also be used for diagnosis of these injuries.

Treatment. Similar to injuries to the MCL, grade I and II sprains are treated conservatively with the RICE protocol, crutches, and physical rehabilitation. In complete tears, primary surgical repair or allograft reconstruction is usually preferable, especially if the injury involves more than just the LCL. Immobilization alone may be less successful for these injuries in patients with severe instability. Cases of mild instability may be treated onoperatively similar to that for lesser-grade sprains.