INTRAUTERINE

GROWTH RESTRICTION

Symmetric or asymmetric reduction in the size

and weight of the growing fetus in utero, compared with that expected for a

fetus of comparable gestational age, constitutes intrauterine growth

restriction. This reduced growth may occur for many reasons, but most

occurrences represent signs of significant risk of fetal death or jeopardy to

the fetus. Some authors advocate identifying fetuses with growth between the

10th and 20th percentiles as suffering “diminished” growth and at intermediate

risk for complications. Problems of consistent definition make estimates of the

true prevalence of growth restriction difficult, but by most definitions it

occurs in 5% to 10% of pregnancies.

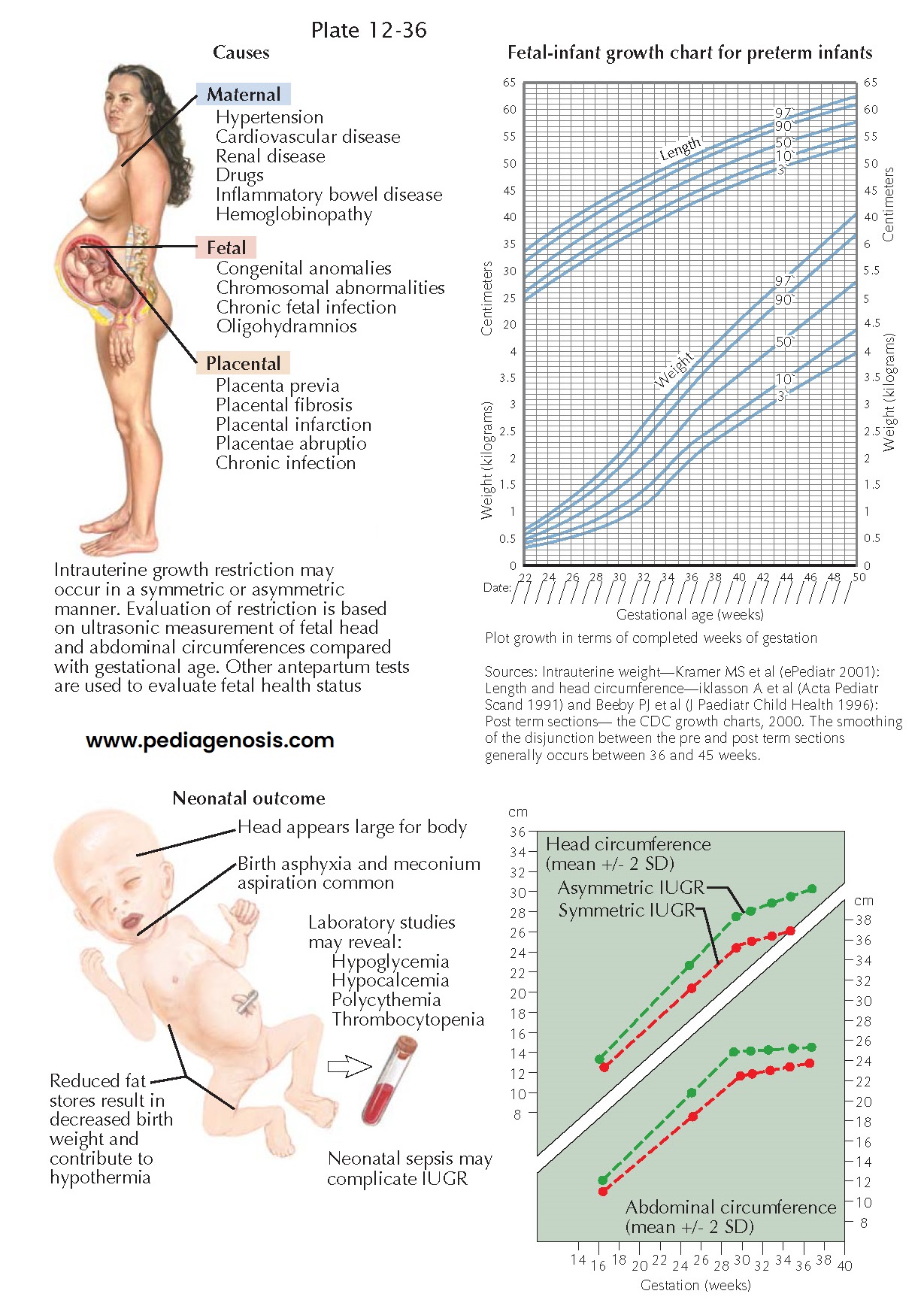

The risk of intrauterine growth restriction increases with the presence of maternal conditions that reduce placental perfusion (hypertension, preeclampsia, drug use, smoking) or those that reduce the nutrients available to the fetus (chronic renal disease, poor nutrition, inflammatory bowel disease). Abnormalities of placental implantation or function can result in significant reduction in nutrient flow to the fetus. The risk is also higher at the extremes of maternal age: for women less than 15 years old the rate of low birth weight is 13.6% compared with 7.3% for women between 25 and 29 years old. When multiple gestations are excluded, the rate for women older than 45 years is greater than 20%. Multiple pregnancies, especially higher order multiples, are at increased risk for growth restrictions. In most cases of growth restriction, no specific cause is identified.

Growth-restricted infants

are at risk for progressive deterioration of fetal status and intrauterine

fetal demise (twofold increased risk). (There is an 8- to 10-fold increase in

the risk of perinatal mortality: growth restriction is the second most

important cause of peri- natal morbidity after preterm birth.) Long-term

physical and neurologic sequelae are common. The risk of adverse outcome is

generally proportional to the severity of growth restriction present.

Overt signs of significant

fetal growth restriction may be absent until a significant reduction in growth

has occurred. (Physical examination of the mother may miss up to two-thirds of

cases; ultrasonography can exclude or verify growth restriction in 90% and 80%

of cases, respectively.) Signs suggestive of growth restriction include a

discrepancy between the externally measured size and what would be expected for

the gestational age. On ultrasonographic examination, the fetus will show

measures of long bone growth or abdominal or head circumference that are

discordant with each other or those expected for the anticipated gestational

age. Oligohydramnios may also be present. The early establishment of a reliable

estimated date of delivery is critical to the accurate detection of a

decelerated rate of fetal growth. The most accurate diagnosis will also be

based on serial examinations that provide information about the growth of the

individual fetus.

Intrauterine growth

restriction must be distinguished from constitutionally

small-for-gestational-age infants, who are not at increased risk. Asymmetric

restrictions in growth argue against a constitutional cause. Early intrauterine

insults are more likely to result in symmetric growth restriction, whereas

later insults result in asymmetry.

Similarly, intrinsic factors generally cause symmetric restriction; extrinsic

factors generally cause asymmetric restriction.

When intrauterine growth restriction is suspected or documented, enhanced fetal assessment and antenatal fetal testing (including nonstress testing, biophysical profiles, and /or contraction stress tests) should be planned. Doppler velocimetry of the umbilical arteries has been demonstrated to be strongly predictive of fetal death when reversed or absent and diastolic flow occurs in the presence of IUGR. Patients at risk because of maternal disease should have early assessment of fetal growth (biparietal diameter, head circumference, abdominal circumference, and femur length) with frequent remeasurement as the pregnancy progresses. This may need to be done as often as every 2 to 3 weeks in severe cases. Careful feta monitoring during labor is indicated for these infants.