Insomnia

Most

people experience occasional insomnia sometime in their lives. However, a

diagnosis of insomnia disorder, which is present in 10% to 15% of adults,

requires a symptom, that is, difficulty with sleep onset, sleep

maintenance, or nonrestorative sleep; a frequency and duration present

on most nights over a period of at least 4 weeks; and a consequence,

associated distress, or social occupational dysfunction. Insomnia disorder is

most commonly comorbid (75%), in which the insomnia occurs in the

context of a medical, psychiatric, or sleep disorder that initiated or

maintained the sleep disturbance, or primary insomnia, with no comorbid

disorders.

Insomnia disorder is more common with increasing age, female gender, poor physical health, and increased social and familial stress. Often, this is a chronic condition, with 50% of insomnia disorder patients continuing to meet criteria after 3 years, particularly with more severe symptoms. However, specific insomnia symptoms (initial insomnia, nocturnal awakenings) are often dynamic, shifting over the course of the disorder. In comorbid insomnia, sleep disturbance is a marker of greater medical, neurologic, and psychiatric illness severity. Insomnia disorder is an independent risk factor for incident major depressive episodes. It is not established whether comorbid insomnia treatment improves outcomes in such disorders. Insomnia sufferers have an increased risk of hypertension and diabetes.

The construct of

hyperarousal helps understand much of the physiology of insomnia disorder,

although it is unclear whether the hyperarousal is a cause or consequence (or

both) of insomnia. Evening cortisol elevations, increased body temperature and

basal metabolic rate, waking EEG patterns, elevated glucose metabolism (using

positron emission tomography [PET]) during non-REM sleep, and reductions in

brain GABA during wakefulness all point to nervous and autonomic system

hyperarousal in insomnia disorder. Insomnia disorder may not be primarily a

nocturnal disorder but rather something that actually lasts throughout the

24-hour day, with insomnia its primary expression.

Insomnia neurobiology is

not fully defined, although advances in sleep biology provide guidance to

potential CNS substrates. The brain contains multiple systems promoting sleep

and others enhancing wakefulness. Pedunculopontine and laterodorsal tegmental

nuclei (PPT and LDT, respectively) cholinergic neurons innervate the

thalamus and cortex firing most actively during wakefulness. Similarly, noradrenergic,

serotonergic, and histaminergic cells in the locus coeruleus, raphe

nucleus, and tuberomammilary nucleus project to the lateral hypothalamus,

thalamus, and frontal cortex, respectively, and fire most actively during the

waking state. Orexin-containing

cells in the lateral

hypothalamus project widely to the cerebral cortex and fire actively during

waking to support arousal. The latter receive afferents from monoaminergic

brainstem arousal centers, also providing extensive input to these centers. The

cortex itself provides assistance to the arousal centers with reciprocal

innervations.

GABAergic-containing

neurons in the

ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) promote sleep by inhibiting arousal

centers. Thus our current simplified under- standing of sleep physiology

informs us that redundant and interactive neural systems control sleep. It is

not surprising that despite a powerful sleep drive, there are many

neuroanatomic substrates for pathology to develop. Thus insomnia may be related

to either inadequate

inhibitory activity from VLPO sleep- promoting neurons or excess brainstem

activation of arousal centers, or even simultaneous activation of both

excitatory and inhibitory influences, leading to unstable sleep states.

The multiple neural

systems controlling sleep provide diverse targets for behavioral and

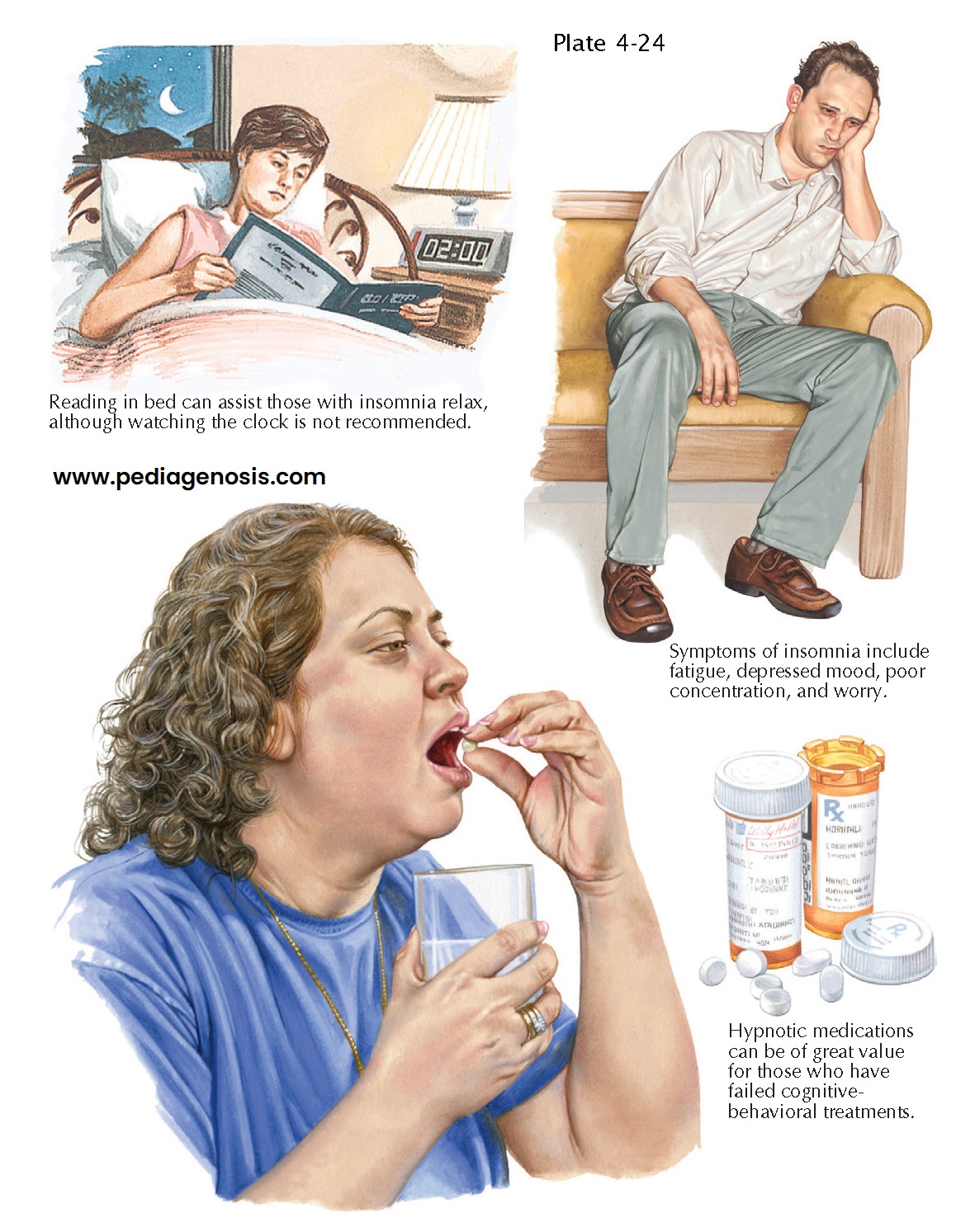

pharmacologic intervention for insomnia treatment. Cognitive-behavioral therapy

for insomnia (CBT-I) includes education about productive sleep habits (sleep

hygiene), reduction of time awake in bed (stimulus control), sleep restriction

to produce sleep deprivation and increase sleep drive, instruction in

relaxation techniques such as meditation and progressive muscle relaxation, and

substitution of realistic attitudes about the consequences of sleeplessness for

prevailing cata- strophic beliefs. CBT-I is effective for improving sleep

satisfaction and reducing wake time

before sleep and during

the night.

Marketed medications known to assist with sleep have existed for more than 100 years, although alcohol and opioids have been used for this purpose for much longer. The commonly prescribed medications bind to benzodiazepine receptors, an allosteric site on the GABA-A receptor, enhancing GABAergic (inhibitory) transmission. Many benzodiazepine receptor agonists exist, and they differ from each other predominantly only in their half-life. These medications are also anticonvulsant, anxiolytic, and myorelaxant and may produce tolerance, physical dependence, and with-drawal symptoms upon rapid discontinuation. There-fore their use is controlled. Other common medications used to promote sleep act at the monoaminergic receptors involved in CNS arousal. For instance, drugs with antihistaminergic properties are available for treatment of allergic reactions, as antidepressants and antipsychotics. Other drugs bind to the melatonin receptor in the CNS, promoting sleep by uncertain mechanisms.