INJURY TO PELVIS

FRACTURE

WITHOUT DISRUPTION OF PELVIC RING

Injuries to the pelvis range from the most trivial to

the most life threatening. In general, the severity of an injury is determined

by the degree of disruption to the pelvic ring. Fortunately, many fractures

about the pelvis do not affect its integrity at all (see Plate 2-63).

|

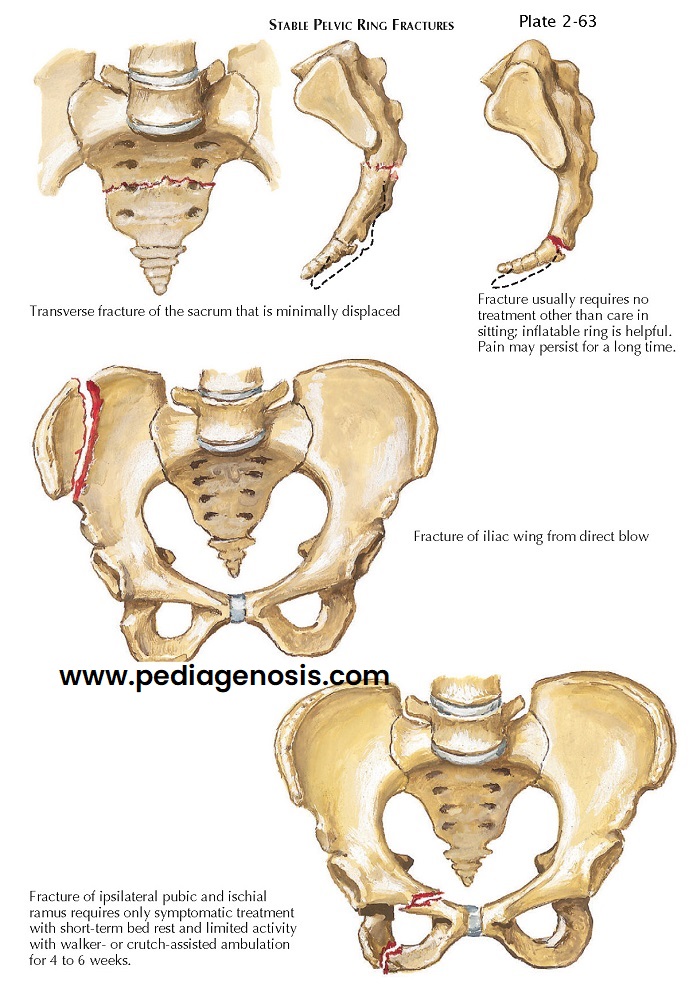

| STABLE PELVIC RING FRACTURES |

Avulsion

In athletes, avulsions of bone from the pelvis due to strong muscle contractions are relatively common. These fractures occur at the anterior superior iliac spine as a result of the strong pull of the sartorius muscle, at the anterior inferior iliac spine from the pull of the rectus femoris muscle, and at the ischial tuberosity from the forceful contraction of the hamstring muscles. Most fractures can be treated with activity modification and medications until pain ceases. Patients may gradually resume athletic activities, usually attaining complete functional recovery within 3 months.

Fracture of Iliac Wing

An isolated fracture of the iliac wing, or Duverney

fracture, is not uncommon, usually resulting from a direct compressive force to

the lateral aspect of the pelvis. The strong muscle attachments on the fragment

usually minimize its displacement; and although blood loss may be substantial,

shock is not common. Radiographic examination must determine whether the

acetabulum is involved or if the sacroiliac joint is disrupted. Management of

the fracture involves bed rest on a firm mattress until the patient is

comfortable enough to be mobilized, followed by gradual, protected weight

bearing until all symptoms resolve. Occasionally, an ileus develops that is not

due to abdominal visceral injury. This complication is usually relieved with

nasogastric suction and intravenous administration of fluids.

Fracture of Pubic or Ischial Ramus

An isolated fracture of a single pubic or ischial

ramus is a fairly uncommon injury; it usually occurs in elderly persons as a

result of a fall. In this type of fracture, the pelvis remains extremely stable

because the obturator foramen is a rigid, bony circle. A fracture of a pubic or

ischial ramus must be differentiated from an impacted fracture of the femoral

neck because treatments differ markedly. A fracture of one pubic or ischial

ramus without visceral or vascular injury requires only bed rest until symptoms

abate sufficiently to allow progressive mobilization with a gradual increase in

weight bearing.

Fracture of Sacrum

Transverse fractures of the sacrum are usually caused

by direct impact and typically have a slightly anterior displacement. Diagnosis

is based on a history of injury and evidence of pain, swelling, and tenderness

over the posterior aspect of the sacrum. Neurologic dysfunction may occur,

evidenced by urinary retention or decrease in rectal tone. The examiner must

take extreme care during the rectal

examination, especially during palpation along the anterior surface of the

sacrum, to avoid converting a closed sacral fracture into an open fracture

through the rectum, which increases the risk of serious contamination of the

retroperitoneal space. If neurologic deficit is either absent or improving,

conservative treatment is indicated. If a neurologic lesion compromises bowel

or bladder function, surgical decompression

should be considered.

This fracture is usually caused by a direct blow to

the posterior aspect of the coccyx. Symptomatic management suffices, but

discomfort may persist for a long time.

FRACTURE OF ALL FOUR PUBIC RAMI

When the pelvic ring is injured at more than one site,

the potential for instability increases correspondingly. Fractures of all four

pubic rami disrupt the structural integrity of the anterior portion of the

pelvic ring (see Plate 2-64). This injury commonly results from a fall on the front of the pelvis

or from lateral compressive forces on the pelvic ring. In about one third of patients,

major trauma to the lower urinary tract occurs as well. Treatment focuses on

preventing any further displacement of the fracture fragments. Bed rest, with

the patient in a semi-sitting position to relax the abdominal musculature, is

followed by mobilization as soon as symptoms allow.

STRADDLE FRACTURE AND LATERAL COMPRESSION INJURY

LATERAL COMPRESSION INJURY

Double breaks in the pelvic ring are often due to

lateral compressive forces (see Plate 2-64). Most of these

fractures are stable because the forces cause impaction of the posterior pelvic

complex, leaving the posterior ligaments intact. If the force continues or

increases, the posterior sacroiliac ligaments may tear, producing an

instability in the injured hemipelvis.

This injury often includes fractures of the superior

and inferior pubic rami; therefore, the anterior and posterior injuries are on

the same side. When the patient is placed in the supine position, the displaced

hemipelvis often reduces spontaneously. Radiographs may reveal only minimal

displacement, but the examiner must remember that the degree of initial

deformation of the hemipelvis is not known, and significant visceral

injury may be present.

When a lateral compressive force is accompanied by a

rotational force, the anterior fracture often occurs on the side opposite the

posterior fracture; for example, an impacted fracture may occur on the left

side of the sacrum while fractures of the inferior and superior pubic rami

occur on the right side. The hemipelvis then displace’s superiorly and medially,

causing the leg to appear internally rotated and shortened. The position of the

hemipelvis generally remains stable, although the malrotation may compromise

future function. Correcting this rotational deformity may create instability when the impacted posterior injury is reduced.

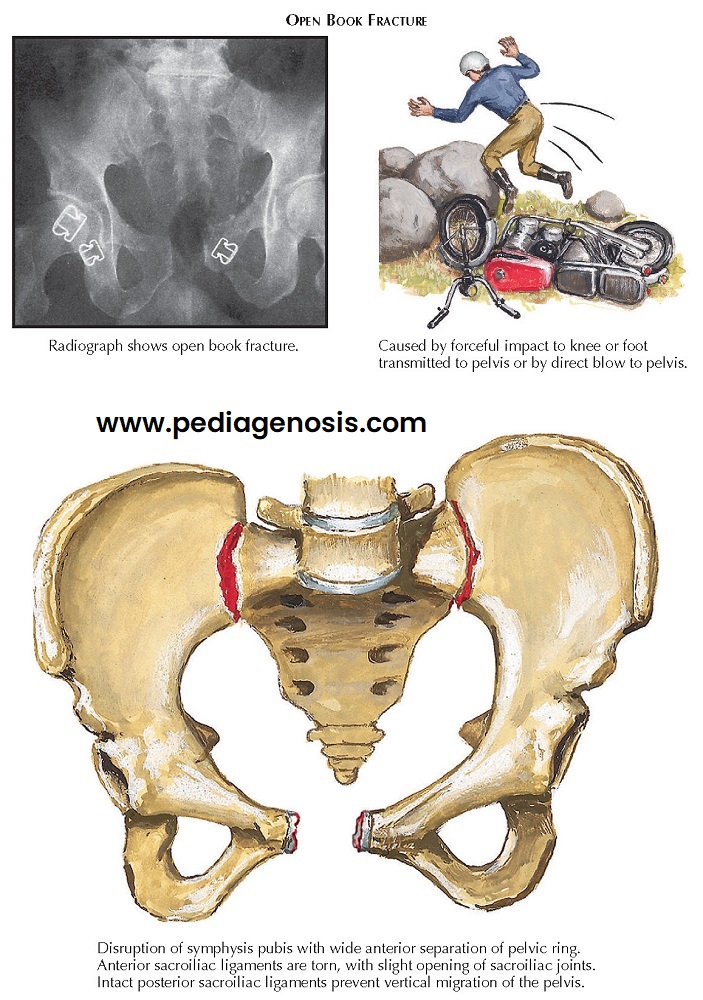

ANTEROPOSTERIOR COMPRESSION FRACTURE

Anteroposterior compression, or open book, fractures

of the pelvis are usually caused by a forceful blow from in front of the pelvis

through the anterior superior iliac spines or by force applied to externally

rotated femurs (see Plate 2-65).

However, a blow from the rear against the posterior superior iliac spines may

produce a similar injury that is characterized by disruption of the pubic

symphysis and the anterior sacroiliac ligaments. Injuries range from an

isolated rupture of the pubic symphysis to complete separation of the pubic

symphysis accompanied by bilateral anterior subluxation of the sacroiliac joints.

Because the sacrospinal ligaments resist external rotation of the pelvis, a

separation of 2.5 cm or greater of the symphysis suggests that the sacrospinal

ligaments have ruptured or have avulsed bone from the sacrum or ischial spine.

Most important, the very strong posterior sacroiliac ligaments remain intact.

The open book fracture is therefore relatively stable, and treatment focuses on

closing the pelvic ring.

The pelvic ring can be closed with or without surgery.

In nonsurgical treatment, crossover slings are used to bring the two pelvic

halves together. In 3 to 4 weeks, when the soft tissues have healed

sufficiently, the pelvic slings are replaced with a mini spica cast and

ambulatory treatment can be initiated. If surgical treatment is chosen, ORIF is

performed, using a plate to stabilize the pubic symphysis. The planning of

treatment for this injury must be clearly distinguished from the treatment for

a vertical shear injury of the pelvis. Because the initial radiographs of both

injuries may appear similar, differentiation requires careful physical examination

and supplemental imaging, including CT of the posterior pelvic complex.

VERTICAL SHEAR FRACTURE

Vertical shear, or Malgaigne, fractures of the pelvis

result from severe trauma (see Plate 2-66). The force may cause unilateral or

bilateral injuries to the posterior pelvis and severe and sometimes

life-threatening injury to the soft tissue contents of the pelvic cavity. The

injury to the anterior pelvis may include disruption of the pubic symphysis

with or without fractures of two, three, or four pubic rami. The posterior

injuries may be fractures of the sacrum, dislocations of the sacroiliac joint,

fractures of the ilium, or fracture dislocations of the sacroiliac joint,

including fractures of the sacrum or the ilium.

Avulsion fractures, particularly of the ischial spine

or the transverse process of the fifth lumbar vertebra, also occur in major

disruptions of the posterior pelvis. Complete instability of the affected

hemipelvis indicates disruption of the sacrotuberal and sacrospinal ligaments.

Because vertical shear fractures are caused by considerable force, many involve

vital pelvic and abdominal tissues of the gastrointestinal, genitourinary,

vascular, and nervous systems.

If the posterior hemipelvis on one side remains

intact, the disrupted half can be brought to the intact side and stabilized.

When both ilia are disrupted from the sacrum, stabilization is much more

problematic. The aim of treatment soon after injury is to reapproximate the injured hemipelvis to the uninjured side using

closed manipulation. After anesthesia or analgesia with significant muscle

relaxation is obtained, the patient is positioned injured side up, with an

assistant supporting the legs. The examiner pushes the displaced ilium downward

and forward. If the reduction is successful, skeletal traction is often used to

maintain it until significant healing of soft tissue or bone occurs.

Because many Malgaigne fractures are grossly unstable,

manipulative reduction is largely unsuccessful, and either external or internal

fixation of the hemipelvis is needed. Fixation with an external fixation device

provides relative immobilization of the hemipelvis; the stability is greater

than that provided by manipulative reduction and subsequent traction. However,

attempts to attain and maintain anatomic reduction with

external fixators are usually

unsuccessful.

ORIF of both

displaced components provides the best stabilization of vertical shear

fractures. Two plates may be used to secure the disruptions in the pubic

symphysis and two bolts inserted to stabilize a longitudinal fracture of the

sacrum.

VASCULAR AND VISCERAL TRAUMA

Vascular and visceral injuries are the chief causes of

deaths associated with pelvic fractures. The likelihood of associated injury is

directly related to the severity of the fracture.

Pelvic fractures normally cause bleeding from injured

vessels of the pelvic marrow or from torn pelvic or lumbar arteries and veins

and formation of a hematoma. The extent of the bleeding depends on the severity

of the vascular and bone injuries, and the risk of death is directly linked to

the severity of the hemorrhage. Patients with double breaks in the pelvic ring

require transfusions twice as often as patients with single breaks or with

fractures of the acetabulum. Persistent severe hemorrhage may warrant emergent

investigation with transfemoral arteriography to identify bleeding sites and

selective embolization using blood, gelatin, or other such substances.

Arteriography may be used to identify injuries to large arteries. Military antishock

trousers may be used to stabilize the fracture and to help diminish blood loss.

Frequently, pelvic fractures cause injuries of the

lower urinary tract. Clues to such injuries include blood at the urethral

meatus or hematuria found on urinalysis. In men, rectal examination may reveal

a high-riding or free-floating prostate, which usually indicates injury to the

lower urinary tract. Urethrography is performed to determine whether the

anterior portion of the urethra is injured. If the urethrogram appears normal,

a catheter should be passed gently through the urethra into the bladder. The

catheter must not be forced. If this procedure is accomplished, further

radiographic studies can determine whether an intraperitoneal or an extra-peritoneal bladder injury is present.

|

| VERTICAL SHEAR FRACTURE |

Most complete transections of the urethra are treated

by diverting the urine stream through a suprapubic catheter placed into the

bladder and, later, with repair or reconstruction of the urethra.

Intraperitoneal ruptures of the bladder are repaired with suprapubic drainage

to decompress the bladder. Depending on the extent of the tear, extraperitoneal

ruptures may not require surgical repair; adequate drainage of the bladder is necessary to allow the laceration to heal.

The examiner must search diligently for injuries of the lower gastrointestinal tract, especially about the rectum and the anus. Blood found on rectal examination suggests that the lower gastrointestinal tract has been lacerated by bone fragments, with possible severe contamination of the extraperitoneal pelvic space. If the rectum or anus is lacerated, standard treatment includes performing a washout of the distal rectal lumen and creating a diverting colostomy to minimize pelvic contamination. In women, a careful vaginal examination is performed to detect lacerations of the vagina, which could lead to contamination and infection of the pelvis.