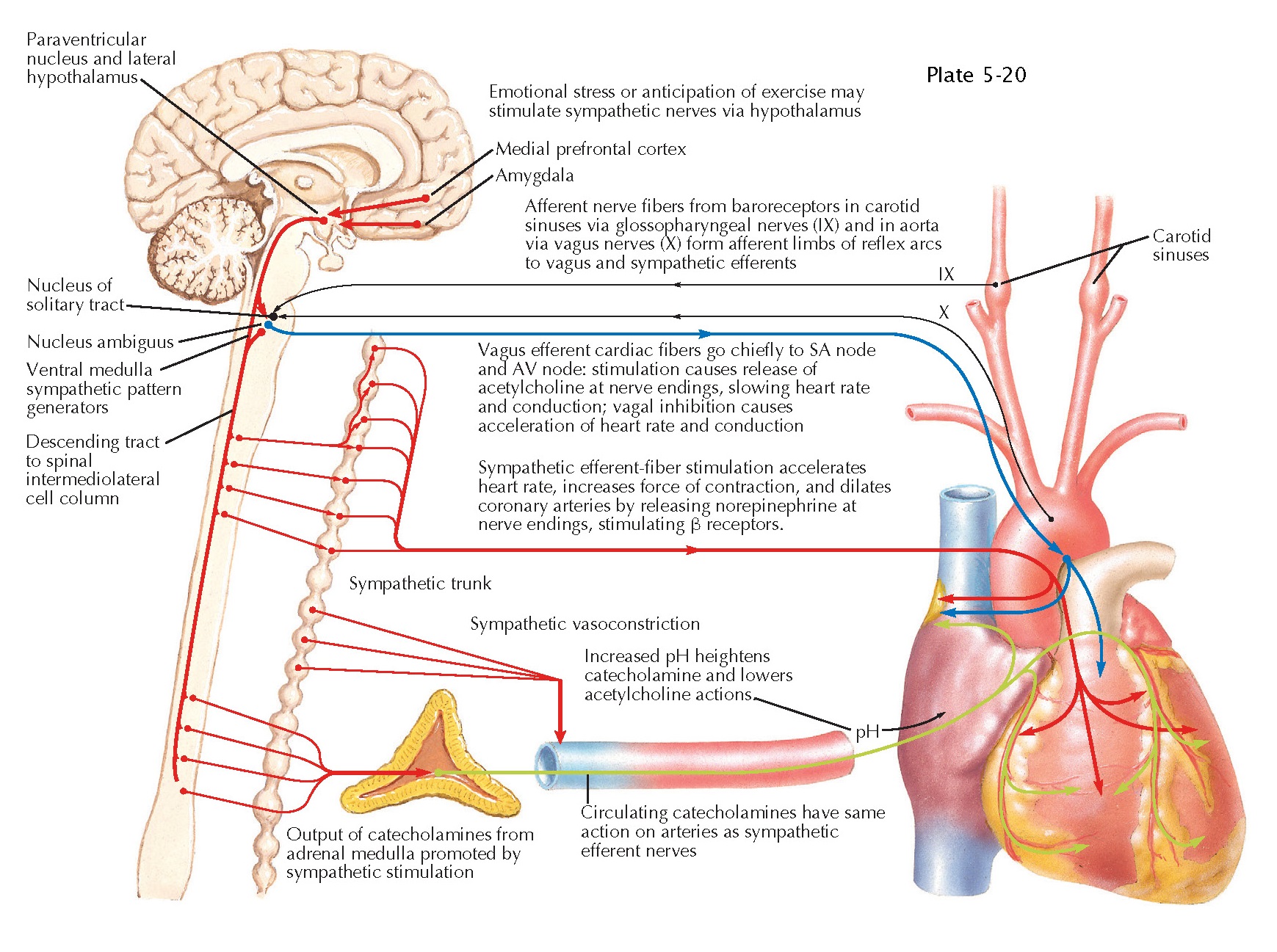

Hypothalamic Regulation of Cardiovascular Function

The hypothalamus is a key component of a central nervous system (CNS) network that governs the heart and circulation. Different behaviors, ranging from emotional responses to motor activities, require activation of different components of the cardiovascular control network. Neurons in the cerebral cortex send inputs to the medial prefrontal cortex, particularly the infralimbic cortex, and the amygdala. These send axons to the hypothalamic neurons that govern cardiovascular response, including the paraventricular nucleus and lateral hypothalamic area. The descending hypothalamic axons innervate brainstem sites involved in producing patterns of cardiovascular response, such as the parabrachial nucleus and both ventromedial and ventrolateral medullary reticular formation.

The

parabrachial nucleus receives visceral sensory and pain inputs, and organizes

patterns of cardiovascular response seen during arousal due to pain,

respiratory distress, or gastrointestinal discomfort (increased blood pressure

and heart rate). It does this by direct projections to sympathetic and

parasympathetic cell bodies, as well as to medullary pattern generators.

In the medulla,

there are distinct pattern generators in the ventromedial and ventrolateral

areas. The ventromedial medulla receives inputs from hypothalamic cell groups

involved in thermoregulation, and it organizes patterns of sympathetic response

necessary for thermogenesis (increased heart rate and activation of brown

adipose tissue, with shifting of blood flow from cutaneous to deep vascular

bed). This also requires elevation of heart rate to deal with the increased

cardiac demand of hyperthermia. The ventrolateral medulla, by contrast produces

patterns of cardiovascular response necessary for maintaining blood pressure

during erect posture, called baroreceptor reflexes.

Other

descending hypothalamic axons go directly to the nucleus of the solitary tract,

as well as the preganglionic neurons in the nucleus ambiguus in the medulla,

which control heart rate through the vagus nerve and the intermediolateral

column of the spinal cord, which controls vasoconstriction. These may produce

patterns of autonomic activation that are organized at a hypothalamic level,

such as stress or starvation responses.

The brainstem

targets of this descending system coordinate cardiovascular reflexes. For

example, the carotid sinus nerve (a branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve) and

the aortic depressor nerve (a branch of the vagus nerve) bring information to

the nucleus of the solitary tract about aortic and carotid stretch. When blood

pressure is high, neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract activate

cardiovagal neurons in the nucleus ambiguus to slow the heart and inhibit

neurons in the ventrolateral medulla that maintain tonic blood pressure by means

of activating sympathetic preganglionic vasoconstrictor neurons. This

baroreceptor reflex can be modified by descending hypothalamic input so that

during times of stress, for example, there can be a simultaneous increase in

blood pressure and heart rate without activating the baroreceptor reflex.

Projections from the hypothalamus to the intermediolateral column can directly activate sympathetic ganglion cells concerned with cardioacceleration and the strength of contraction, to increase cardiac output. Other descending hypothalamic axons can contact adrenal preganglionic neurons, resulting in increased circulating adrenalin, wh ch also increases vasoconstriction and cardiac output.