GESTATIONAL

TROPHOBLASTIC DISEASE

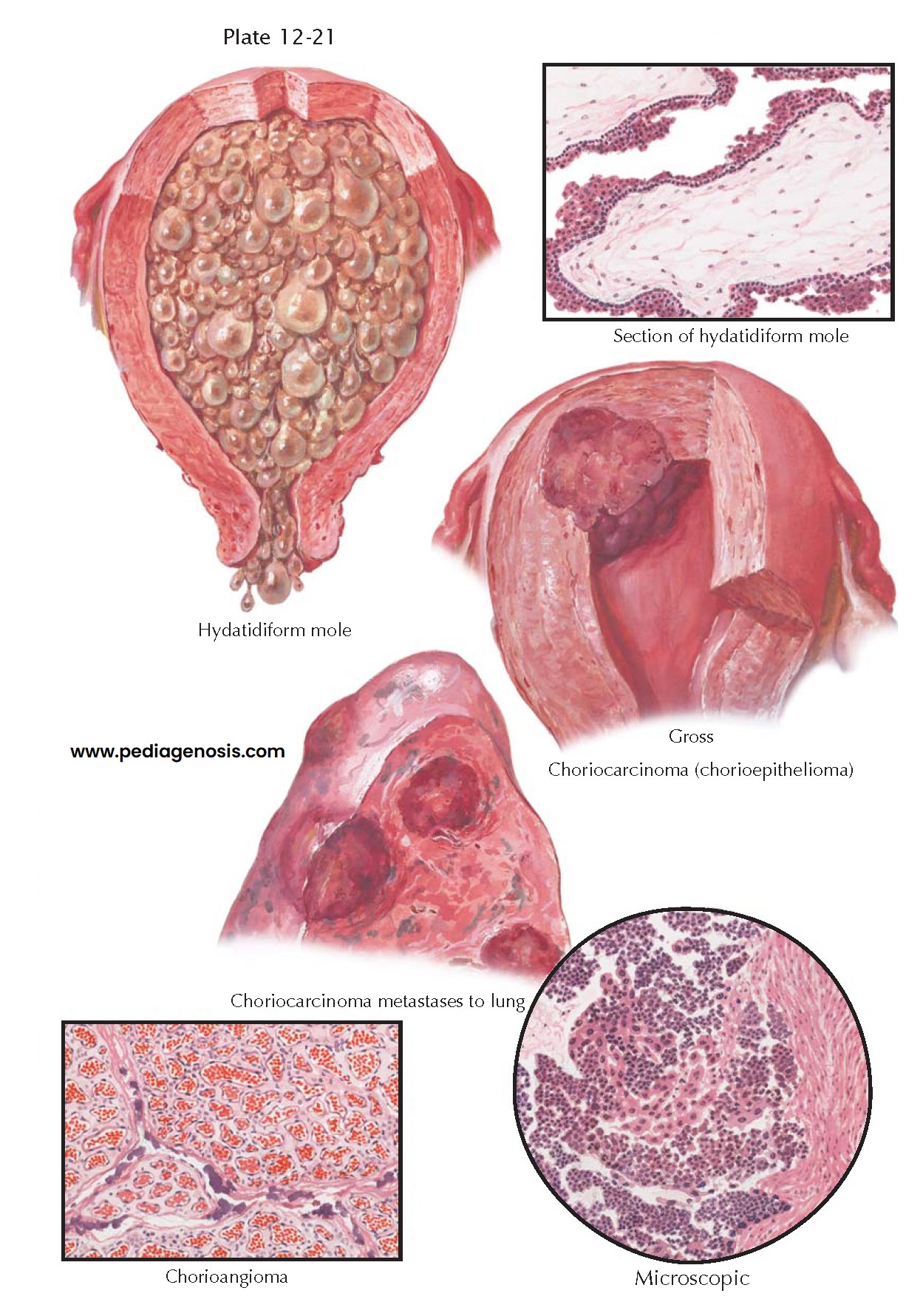

Four neoplasms of placental tissues are known, namely, chorioangioma arising from placental capillaries, hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma arising from trophoblastic tissues, and placental-site trophoblastic tumor. Chorioangiomas are rare benign vascular tumors arising from the primitive chorionic mesenchyme, whose etiology is unknown. They are associated with increased maternal age, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension and are more common in multiple pregnancies. The tumor appears as a solitary, deep red, often-lobulated nodule in the placenta. It is of little clinical significance.

A hydatidiform mole

consists of chorionic villi, which appear as grapelike clusters of vesicles.

Moles are classified as being either complete, in which no fetus is present, or

incomplete (partial), in which both fetus (generally abnormal) and molar

tissues are present. The vesicles resemble youthful villi in that they are

branching structures covered with two or more layers of trophoblastic cells,

but they have no fetal blood vessels, and their stroma is only a loose-meshed

matrix filled with clear gelatinous material. Molar pregnancy occurs in 1 of

1000 to 1500 pregnancies in the United States, and as high as 10 per 1000

pregnancies in Asia. Molar pregnancies have the unique genetic attribute of a

double contribution from the father: complete moles are mostly 46,XX all of

paternal origin, though mitochondrial DNA of maternal origin remains;

incomplete moles are most often triploid (69,XXY or 69,XXX) all of paternal

origin.

The clinical

manifestations are the same as those in normal pregnancy, except that the

uterus enlarges more rapidly than usual and there are exaggerated symptoms of

pregnancy. Diagnosis is facilitated by the passage of some grapelike vesicles,

by the abortion of the mole, or a classic “snowstorm” appearance on

ultrasonography. Molar pregnancies are associated with hypertension,

preeclampsia, proteinuria, nausea, and vomiting (hyperemesis, 8%); visual

changes, tachycardia, and shortness of breath are all possible.

(Pregnancy-induced hypertension in the first trimester is virtually diagnostic.)

The treatment of molar

pregnancies is surgical: evacuation of the uterine contents. This is most often

accomplished via suction curettage. Because of the large size of some molar

pregnancies and a tendency toward uterine atony, concomitant oxytocin

administration is advisable and blood for transfusion should be immediately

available. Once the uterus has been emptied, the patient should be closely

followed for at least 1 year for the possibility of recurrent benign or

malignant disease. Any change in the patient’s examination, an increase in β-hCG titers, or a failure of the β-hCG level to fall below 10 mIU/mL by 12 weeks

after evacuation should be evaluated. Serum hCG levels are generally monitored

every 2 weeks until three consecutive tests are negative, then monthly for 6 to

12 months. Pregnancy should be prevented for about a year, because a rising titer in the nonpregnant woman may

indicate the presence of choriocarcinoma.

Gestational trophoblastic neoplasia is notable for the possibility of malignant transformation, although less than 10% of patients develop malignant changes. Choriocarcinoma, also called chorioepithelioma, is a rare but very malignant tumor that metastasizes early to the lungs. It is composed of both syncytial and cytotrophoblastic cells that do not form chorionic villi but grow destructively into the uterine wall. In about half the cases, it follows a hydatidiform mole; in the others, it follows an abortion or a term pregnancy or is, in rare instances, associated with a teratoma. Roughly 80% of molar pregnancies follow a benign course after initial therapy. Between 15% and 25% of patients develop invasive disease, and 3% to 5% eventually have metastatic lesions. The prognosis for patients with primary or recurrent malignant trophoblastic disease is generally good (>90% cure rate). Fewer than 5% of patients will require hysterectomy to achieve a cure for choriocarcinoma.