DISORDERS OF THE PATELLA

|

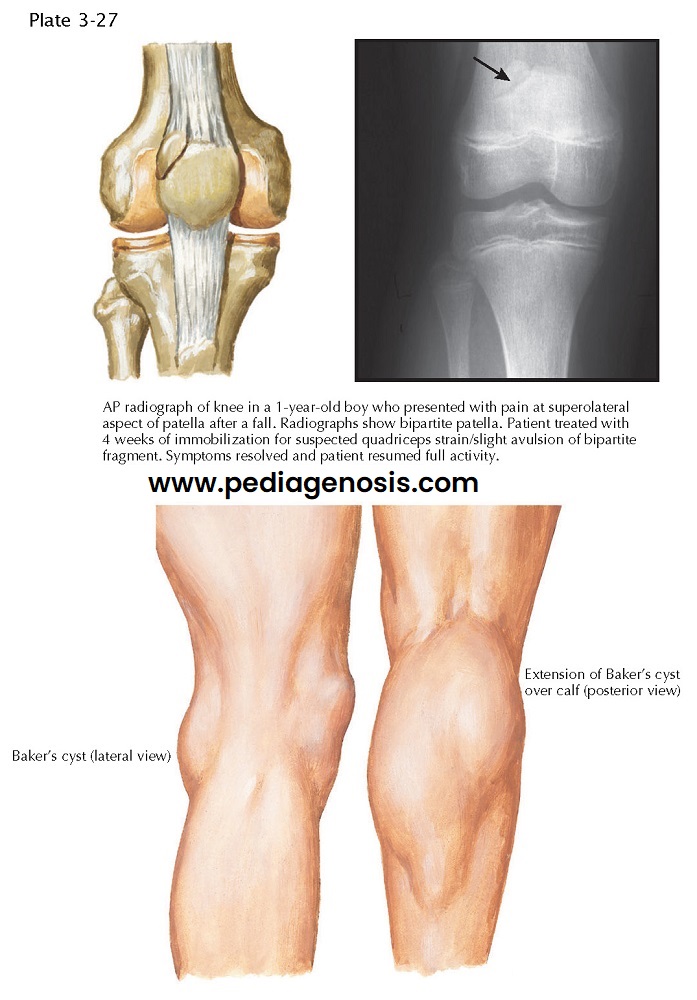

| BIPARTITE PATELLA AND BAKER’S CYST |

Congenital fragmentation of the patella is relatively common. One type, bipartite patella, occurs in 1% to 2% of the population. This anatomic variant represents a true synchondrosis (a joint whose surfaces are connected by a cartilaginous plate). Most fragmented patellae remain asymptomatic, but, occasionally, direct trauma to the patella disrupts the synchondroses, causing symptoms that mimic those of a fracture.

A true fracture is differentiated from congenital

bipartite patella on the basis of a history of significant trauma to the

patella, hemarthrosis of the knee, point tenderness over the defect, and a

sharply outlined fragment seen on the radiograph. If the diagnosis is still

uncertain, CT or MRI can be used to differentiate an acute fracture from a congenital

condition.

Asymptomatic bipartite patellae do not require any

treatment. In symptomatic cases, conservative treatment, including a period of

immobilization followed by stretching and strengthening exercises for the

quadriceps and hamstring muscles, is usually sufficient. If the fragment

remains symptomatic, it can be excised along with a lateral retinacular

release.

PATELLA ALTA AND INFERA

Patella alta refers to an abnormally high patella in

relation to the femur. Patella alta predisposes to patellar subluxation and

dislocation with resultant repetitive microtrauma and inflammation of the

patellofemoral joint (patellofemoral chondrosis).

Patella infera indicates an abnormally low patella.

Although it occurs most often secondary to soft tissue contracture and

hypotonia of the quadriceps muscle after surgery or trauma to the knee, it may

also represent a congenital variant.

Imaging. The position

of the patella can best be determined on the lateral radiograph with the knee

flexed 30 degrees. Insall’s ratio describes that the length of the patellar

ligament is usually equal to the diagonal length of the patella. Variations of

more than 20% are considered abnormal.

Treatment. Congenital

patella infera is frequently asymptomatic and requires no treatment. If this

condition develops after injury or surgery, it can be cata- strophic. Prompt

recognition of the condition is of utmost importance because treatment in the

early stages can reverse it. Vigorous rehabilitation of the quadriceps muscles

and mobilization of soft tissue structures around the knee should be instituted

as soon as the complication is recognized.

SUBLUXATION AND DISLOCATION OF PATELLA

The patella depends on both dynamic and static

stabilizers to maintain its proper position in the intercondylar groove.

Although the entire quadriceps muscle contributes to the dynamic stability of

the patella, the contribution of the vastus medialis muscle is critical. The

distal oblique portion of this muscle resists lateral migration of the patella.

The static patellar restraints, which include the bony contour of the distal

femur, the joint capsule, the medial and lateral retinacula, and the medial

patellofemoral ligament (MPFL), are equally important. A flat lateral femoral

condyle (“tabletop” femur) allows the patella to slide laterally quite easily,

whereas a deep intercondylar groove generally keeps the triangular-shaped patella well located. A large Q angle seems to

increase the patient’s susceptibility to subluxation or dislocation of the

patella. The Q angle is formed by the intersection of two lines drawn from the

anterior superior iliac spine and the tibial tuberosity through the center of

the patella. This condition is also often associated with knock-knee and

external tibial torsion and is most commonly symptomatic in adolescent girls

and young women.

Patellar subluxation is the partial

loss of contact between the articular surfaces of the patella and femur. It is

most common when the ligamentous support is loose and when the vastus medialis

muscles are poorly developed or atrophied. Just a weak medial quadriceps muscle permits lateral subluxation, and tightness in

the lateral peripatellar tissues can pull the patella laterally. Patellar

dislocation is the complete loss of contact between the articular surfaces

of the patella and femur. Congenital dislocations are rare and when present

tend to be bilateral and familial. The majority of dislocations are traumatic.

Underdeveloped femoral condyles, insufficient soft tissue restraints, and a

weak vastus medialis muscle all

predispose to patellar dislocation.

Physical Examination. Patients

complain of anterior knee pain, particularly when climbing stairs, and giving

way of the knee. Physical examination reveals tenderness along the medial

aspect of the patella, patellofemoral crepitus, atrophy of the quadriceps

femoris muscle

(especially the oblique portion of the vastus medialis), and increased lateral

mobility of the patella. On physical examination, the patella can normally be

manually displaced both medially and laterally between 25% and 50% of the width

of the patella. Greater movement indicates loose patellar restraints, a finding

frequently seen in adolescent females. A positive apprehension test may be

elicited when the patient forcefully contracts the quadriceps femoris muscle

and feels pain as the examiner attempts to displace the patella laterally. If

the subluxation is not treated, the lateral retinaculum gradually becomes

contracted, exacerbating the abnormal patellofemoral tracking.

Imaging. In addition to

traditional anteroposterior and lateral plain radiographs, it can be beneficial

to obtain an infrapatellar view with the knee flexed 30 to 45 degrees, rather than the traditional “sunrise” or

“skyline” view with the knee flexed beyond 90 degrees. To assess the soft

tissue attachments and stabilizers and bony anatomy the surgeon may choose to

obtain MR images and CT scans, respectively.

Persons at risk for patellar instability may often

exhibit generalized ligamentous laxity and a poorly developed vastus medialis

muscle. When these patients are sitting or standing erect in a relaxed

position, the patellae often face laterally (“owl-eye” patellae). At full

extension, the patella may also deviate laterally outside of the groove (J

sign).

Rupture of the MPFL after lateral dislocation of the

patella causes pain and tenderness along the medial retinaculum. Sometimes, the

vastus medialis muscle is avulsed from the medial intermuscular septum, causing

pain in the medial region of the knee. However, patellar dislocation should not

be confused with a sprain of the MCL. After an acute dislocation of the

patella, gentle manual lateral subluxation of the patella produces dis-comfort, a finding not seen with injury to the MCL.

CHONDROMALACIA PATELLAE

The term chondromalacia describes the softening

and fissuring of the articular hyaline cartilage and frequently refers to the

undersurface of the patella. Chondro-malacia may result from an excessive load

on the patellofemoral joint, but disuse may be a contributing factor.

In clinical practice, chondromalacia is used to describe

inflammation of the articular surface of the patellofemoral joint

(patellofemoral chondrosis) or degeneration of this joint (patellofemoral

arthrosis). Patellofemoral chondrosis is most common in young women.

Contributing factors include weakness and tightness in the quadriceps muscle,

abnormalities of lower limb alignment (knock-knee, bowleg, an abnormally

positioned patella), and obesity. Patellofemoral arthrosis usually occurs with

aging. Patients affected by this will often report pain in the anterior knee

while climbing stairs or sitting for long periods.

Physical Examination. On

examination, compression of the patella may cause pain along the medial and

lateral retinacula and the patellar ligament. Compression of the patella during

flexion and extension of the knee usually elicits crepitation and discomfort;

swelling may also be present. MRI may also reveal chondral changes along the

undersurface of the patella.

Treatment. Strenuous and

pain-provoking activities should be reduced until symptoms subside. Exercises

to stretch and strengthen

the quadriceps muscle, especially the vastus medialis muscle, should be

initiated immediately. In refractory cases, patients may also benefit from

arthroscopic shaving of loose articular fragments or lateral release of the

patella, or both. Although removal of the degenerated tissue usually does

little to alleviate the symptoms or to improve the long-term prognosis, it can

decrease crepitation and synovial effusion. A lateral release may relieve

excess patellofemoral contact pressure or denervate a sensitive region.

|

| SUBLUXATION AND DISLOCATION OF PATELLA |

PATELLA OVERLOAD SYNDROME

Patella overload syndrome is a common and painful

condition seen in rapidly growing adolescents whose bones appear to be growing faster than the attached soft tissues. This rapid

growth results in tightness of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles, which can

increase the compression forces between the patella and femur during knee

flexion, causing irritation. Trauma can also contribute to the development of

this condition, particularly if followed by immobilization or disuse. These may

lead to soft tissue contracture, resulting in a tight patellofemoral joint.

Patients complain of a toothache-like pain over the anterior surface of the knee, especially along the lateral border of the patella. Conservative management with muscle and soft tissue stretching and strengthening is usually sufficient, but the patella must be protected without further irritation. If exercise causes pain, the routine must be carefully evaluated.