Delirium

and Acute Personality Changes

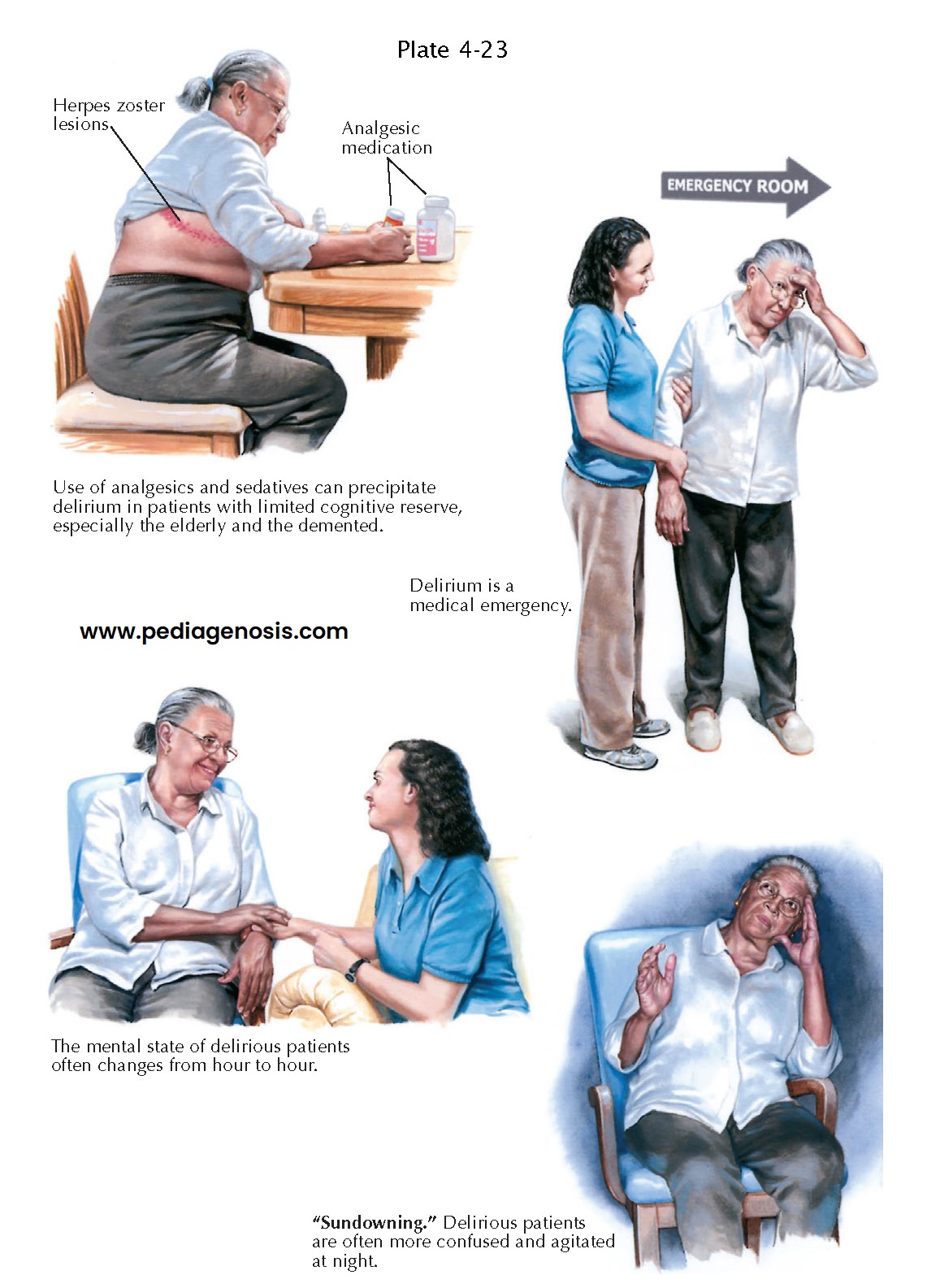

Delirium is an acute confusional state commonly

seen in patients with medical illness, especially among the geriatric

population. Delirium encompasses four key clinical features, including (1) a

disturbance of consciousness with impaired attention and concentration, (2) the disturbance develops over

a short period of time (hours to days) and often fluctuates in

severity. (3) a perceptual disturbance that is not related to a

pre-existing condition such as dementia, and (4) an underlying medical

condition, intoxication, or medication side effect is evident.

Approximately 30% of older patients experience delirium in the course of

hospitalization, with higher rates among more frail patients and those

under-going complex surgery. In the intensive care unit (ICU), the prevalence

of delirium is about 70% as measured by standardized screening and diagnostic

tools.

There are multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms that may cause delirium; there is no final common pathway allowing a simple approach to diagnosis or treatment. The neurobiologic basis of delirium is, therefore, poorly understood, and diagnosis relies on a comprehensive clinical assessment with judicious use of ancillary studies. In general, areas of the brain that govern arousal, attention, insight, and judgment are affected. These include the subcortical ascending reticular activating system (ARAS) and integrated cortical regions. The ARAS predominantly serves arousal mechanisms, whereas integrated cortical function is necessary for proper orientation to person, place, and time, as well as higher cognitive functions.

Of the neurochemical

pathogenic mechanisms of delirium, the best understood is the cholinergic

system. Anticholinergic drugs are commonly associated with delirium in healthy

patients but much more so in the elderly. Conditions that may predispose to

delirium secondary to acetylcholine depletion include hypoxia, hypoglycemia,

thiamine deficiency, and Alzheimer disease. In addition, many commonly used

drugs may precipitate delirium due to secondary anticholinergic effects.

Additional neurotransmitter systems that may precipitate delirium include GABA,

endorphins, neuro-peptides, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Other neuro-chemical

precipitants of delirium include endogenous chemicals, such as proinflammatory

cytokines and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which may explain delirium occurring

in the context of infection/sepsis, surgery, and hip fractures. The

blood-brain barrier is weakened by sepsis, even in pediatric cases. Other

than advanced age, pre-existing CNS disease, such as Alzheimer disease,

Parkinson disease, stroke, etc., accounts for a significant increase in risk

for delirium. Indeed, a new delirium in an elder patient may be a heralding

sign of previously unrecognized or impending dementia.

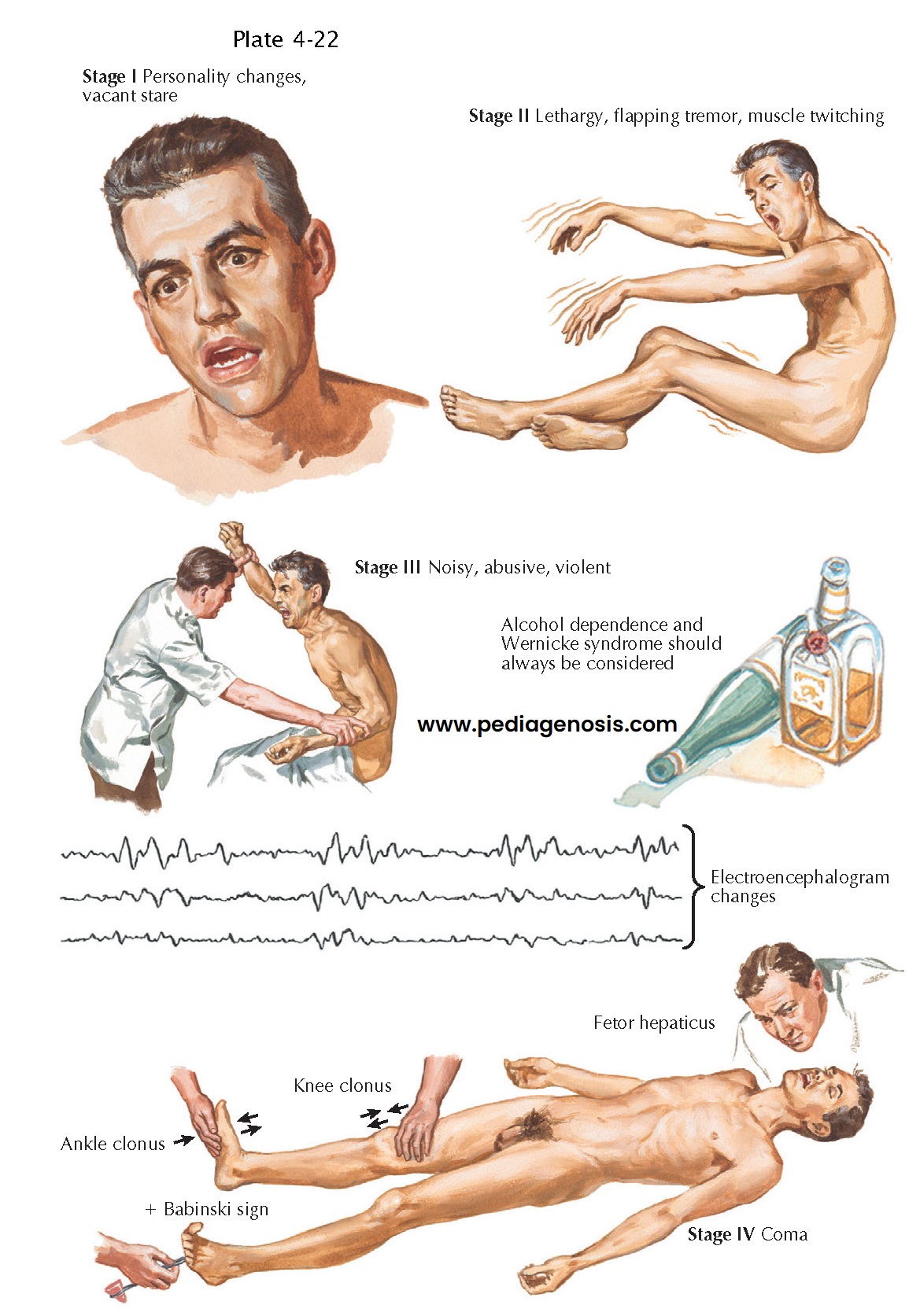

The presentation of

delirium is typically acute, over hours or days, and may persist for days to

months. There may be a prodromal phase, especially in elder patients,

including fatigue and lethargy, sleep disturbance, anxiety and/or depression,

or restlessness. The acuity of onset differentiates delirium from dementia in

most cases, although delirium in a demented patient may be difficult to detect,

especially early in the course. More-over, the severity of confusion may

fluctuate through-out the day, becoming particularly more prominent toward

night-time. Initially, there may be a subtle change in mental clarity,

inattention, and disorientation before more obvious behavior changes take

place. The patient is often very distractible, unable to maintain a cohesive train of thought or action. Patients are typically disoriented

to time. In more advanced cases, patients may become more obviously drowsy

and lethargic, even obtunded. However, the opposite may occur in some forms

of delirium, where the patient becomes hypervigilant, irritable, and

agitated, as seen in alcohol withdrawal. Hallucinations may occur. Cognitive

deficits, including amnesia, aphasia, agnosia, and apraxia may also appear.

Other clinical manifestations may include emotional lability, disturbance of

sleep cycle, motor restlessness, and sometimes motor signs, such as

asterixis, myoclonus, or action tremor. In the elder patient, the most

common presentation is of a withdrawn, quiet state that may be easily mistaken for depression.

Delirium is often

misattributed to psychiatric diagnoses— usually depression and catatonic schizophrenia

in hypoactive deliriums, and personality disorders and psychosis in hyperactive

deliriums. A patient with a first-episode psychosis or mania should be of

typical age, that is, a young adult, and should appear generally well, not diaphoretic,

flushed, befuddled, jaundiced, or clumsy. Psychiatric illness usually does NOT

account for disorientation, and does NOT cause motor symptoms or fevers.

Fluctuations in degree of alertness, variable motor signs, and uneven cognitive

performance are expected in delirium and do not signify a manipulative

personality. Use of antipsychotic medication may enable care, shorten duration

of delirium, and improve mortality,

even when the underlying cause is not psychiatric.

Psychiatric illness is a

diagnosis of exclusion for delirium and should be confirmed with a psychiatric

consultant when suspected. Similarly, if a delirious patient is under

psychiatric care, neurologic consultation should be obtained. Frontal brain

tumors, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, encephalitis, and dementia can all have

delusions, hallucinations, mania, and aggression as manifesting signs.

Repeating sequences of odd behavior, indifferent attitude, amnesia, atypical

age, absence of prior or family history of mental illness, and presence of

primitive reflexes indicate more screening for neurologic disease.

Substance abuse very

frequently leads to various confusional presentations. The use of illicit

substances and overuse of alcohol are usually denied in medical settings;

however, ingestion of toxins and drug overdose, either recreational or

suicidal, should be considered in all cases of delirium. Alcohol,

barbiturates, and benzodiazepines all have life-threatening withdrawal

syndromes, as well as syndromes of intoxication. Antipsychotics are not a

treatment for withdrawal syndromes. Replacement therapy and controlled taper

for alcohol, benzodiazepine, and barbiturate-dependent patients are lifesaving.

Very rarely, anti–N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis, a

novel and significantly underdiagnosed diffuse encephalopathy, manifests

primarily (80%) in women with a combination of psycho- sis, including

catatonia, as well as dyskinesias, memory deficits, and convulsions. The

abnormal movements are varied, often including oral-lingual-facial akathisia

but also choreoathetosis, dystonia, oculogyric crisis, dystonia, rigidity, and

opisthotonos. Often, there is a less than 2-week history of a prodromal febrile

illness, including headache and respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms. This

anti-NMDAR encephalitis is either a paraneoplastic disorder, secondary to an

underlying ovarian teratoma, or a primary autoimmune disorder occurring in

young adults or children. This is potentially reversible if recognized early

and treated with surgery and/or immunosuppression. Prognosis largely depends on

adequate immunotherapy and, in paraneoplastic cases, complete tumor removal.

Regardless of the

individual case, a comprehensive history, examination, and review of the

medical record must be completed to determine the underlying cause(s). Seizures

and focal signs on examination require brain imaging (magnetic resonance

imaging [MRI]/computed tomography [CT]) and/or electroencephalography (EEG) to

assess for acute structural lesions, infection, or inflammation. The nature of

the patient’s underlying medical condition requires standard laboratory tests,

including blood cultures as well as cerebrospinal fluid examination to

demonstrate evidence of possible systemic infections, electrolyte disturbance,

volume depletion, liver failure, uremia, thyrotoxicosis, and other systemic

disorders.

The examiner must

consider potential permanently damaging conditions, such as thiamine deficiency

(Wernicke encephalopathy), herpes encephalitis, or NMDAR encephalitis, all

requiring emergent therapy. A careful review of medications and toxicology

screens is essential. Drug toxicity accounts for 30% of delirium cases;

over-the-counter drugs, such as diphenhydramine, require attention, and other

specific drug syndromes exist

as well. When no mechanism is identified for the acute personality change,

particularly in young women, abdominal/pelvic imaging studies as well as

anti-NMDAR autoantibodies must be evaluated in serum or cerebrospinal fluid to

exclude anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Antipsychotic medications

can precipitate the neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a triad of acute

confusion, rigidity, and hyperthermia. Antipsychotic medications, often

useful for behavioral control of an agitated patient, may also cause their own behavioral

syndrome of severe motor restlessness, or akathisia, which is usually

accompanied by markedly increased muscular tone and cramping. Combinations of

antidepressants, migraine medications, and some antibiotics can trigger the serotonin

syndrome, causing a triad of confusion, autonomic instability, and clonus. Lithium, along with other narrow-window

therapeutic drugs, such as digitalis, can cause delirium even with levels in

the recommended therapeutic range. Lithium toxicity usually manifests with vomiting

or diarrhea, severe tremors, and ataxia, whereas digitalis toxicity often

causes paranoia and hallucinations. Serum levels of any drug the patient is

taking should be checked when available, and all nonessential medications

should be held.

Treatment of delirium requires identification of the underlying medical problem, judicious use of psychoactive medication to keep the patient and others safe from aberrant behavior, and maintaining a peaceful environment. The presence of delirium is a well-established source of increased morbidity and mortality—and a syndrome in urgent need of a diagnosis.