Borderline

Personality Disorder

The term borderline was initially

assigned to those patients who were neither neurotic, nor psychotic, but proved

to be clinically troubling cases. Today, a diagnosis of borderline

personality disorder (BPD) refers to patients characterized by emotional

turmoil and chronic suicidality. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), BPD patients must show a “pervasive

pattern of instability of inter-personal relationships, self-image, and

affects, with marked impulsivity beginning by early adulthood and present in a

variety of contexts.” Specifically, patients must present with at least five

symptoms out of a possible nine that can be organized into four categories:

affective, impulsive, interpersonal, and cognitive.

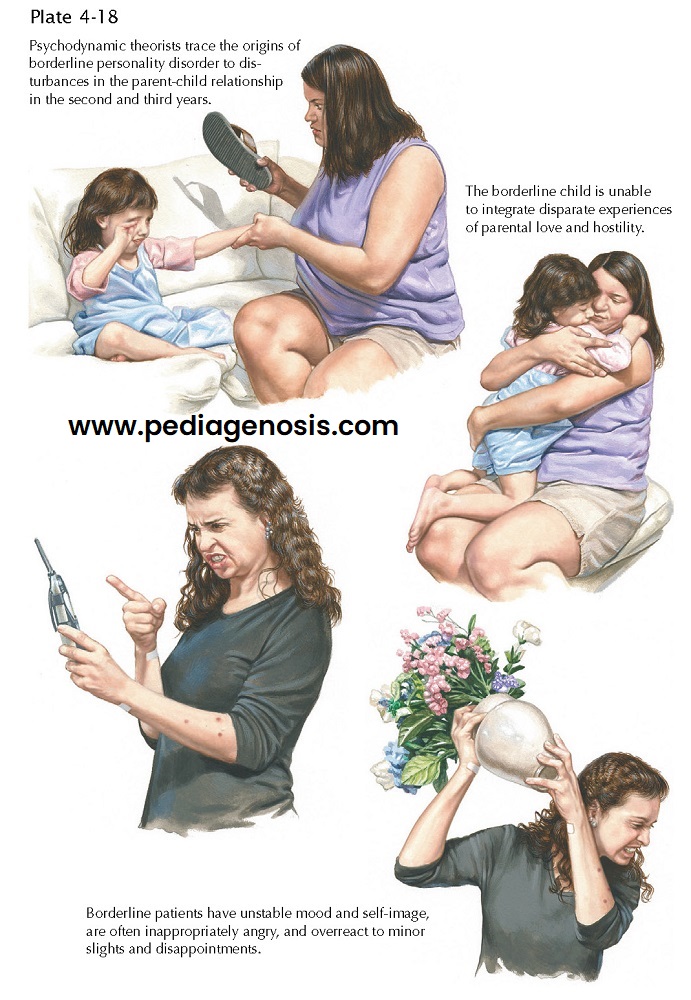

Affective symptoms include extreme reactivity of mood, feelings of chronic emptiness, and inappropriate or intense anger. Impulsive symptoms include recurrent suicidal behavior, including ideation, threats, and suicide attempts, as well as self-destructive acts such as cutting, burning, or scratching oneself. These individuals may exhibit two or more other potentially self-damaging impulsive behaviors, including substance abuse, excessive spending, unusual sexual behavior, binge eating, or reckless driving. Sudden and dramatic shifts in their views of others frequently occur. Within the interpersonal domain, BPD patients may experience intense abandonment fears coupled with inappropriate anger, as well as an unstable sense of self characterized by ever-changing goals and values. Cognitive symptoms can occur under extreme stress and may be experienced as transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms. The modern BPD individual’s behavioral style is self-damaging, functioning below an actual level of intelligence or ability, varying between idealizing and devaluing within interpersonal relationships, and demonstrating an inflexible and impulsive cognitive style.

The prevalence of BPD is

approximately 2% within the general population; the majority are women. BPD

patients generally present clinically at age 18, tend to use more outpatient

treatment services and frequent emergency rooms and psychiatric hospitals. Acts

of self-injurious behavior are common, in particular during the young adult

years. Completed suicide, the most devastating outcome of any psychiatric

illness, occurs in 10% of BPD patients. Comorbid disorders, in particular mood

and substance use disorders, complicate the picture of BPD and interfere with

symptomatic recovery as well as psychosocial functioning. BPD patients are

often undiagnosed because of the symptomatic overlap with other disorders. The

severity and prevalence of BPD decrease with age; approximately 75% of patients

regain close to normal functioning by age 40 years, and by age 50 years, almost

90% recover. Both biologic and psychosocial factors contribute to development

of BPD. Studies of twins have demonstrated a genetic influence in BPD, as well

as for the core symptoms of affective instability and impulsivity. First-degree

relatives of BP individuals evidence higher rates of impulsive disorders.

Serotonergic deficits are linked with impulsivity, although no specific

biologic markers of the overall disorder are yet identified. Psychosocial

factors also contribute; these include family dysfunction, frequent traumatic

childhood events, invalidating environments, and histories of sexual and

physical abuse. While pharmacotherapy plays a role in symptom management,

psychosocial treatments are considered the primary method of treating BPD.

Dialectical behavior therapy

(DBT) is the most heavily researched psychosocial treatment. Rooted in

cognitive-behavioral therapy, DBT uses individual and group therapy to address

impulsivity and affective instability by teaching mindfulness, emotion

regulation, and distress tolerance skills. This has reduced suicide attempts,

hospitalizations and emergency room visits, and treatment drop-out.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy systems training for emotional predictability and

problem solving, and even psychodynamic treatments (i.e., mentalization-based

therapy and transference-focused therapy) demonstrate preliminary encouraging

results.

There is much controversy over the use of pharmacotherapy for BPD. In the United Kingdom, pharmacotherapy is not recommended other than for the treatment of comorbid disorders. Recent meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy appears to demonstrate beneficial effects for several core symptom clusters. Interpersonal pathology was significantly impacted by the antipsychotic aripiprazole. Anticonvulsants, including topiramate, valproate, and lamotrigine, are preferred first-line agents for affective dysregulation, whereas second- generation antipsychotics (SGA) and haloperidol also showed positive results. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) treatment is only recommended for patients experiencing a comorbid axis I condition (i.e., a major depressive episode) that requires antidepressant treatment. No evidence of effectiveness emerged for other symptoms of BPD, that is, impulsive and cognitive components. When selecting a pharmacologic treatment for borderline personality disorder, it is important to consider the potential for misuse or dependence as well as potential toxic effects of overdose. Although many BPD symptoms are treatable with pharmacotherapy, treatment with medications, per se, does not lead to the remission of this disorder.