ANATOMY OF THE KNEE

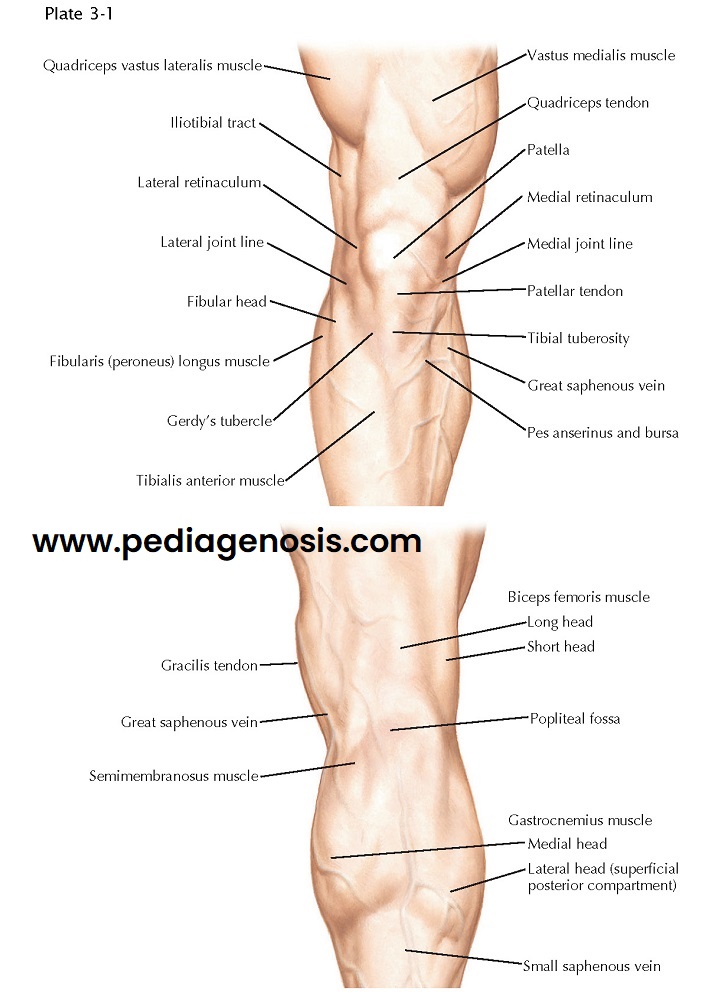

TOPOGRAPHIC ANATOMY OF THE KNEE

The knee is primarily a hinge joint that permits flexion and extension. In flexion, there is sufficient looseness to allow a small amount of voluntary rotation; in full extension, some terminal medial rotation of the femur (conjunct rotation) achieves the close-packed position. The condyles of the femur provide larger surfaces than those of the tibial condyles, and there is a component of rolling and gliding of the femoral surfaces that uses up this discrepancy. As the extended position is approached, the smaller lateral meniscus is displaced forward on the tibia and becomes firmly seated in a groove on the lateral femoral condyle, which tends to stop extension. However, the medial femoral condyle is still capable of gliding backward, thus bringing its flatter, more anterior surface into full contact with the tibia. These movements of conjunct rotation bring the cruciate ligaments into a taut, or locked, position. The collateral ligaments become maximally tensed, and a full, close-packed, and stable position of extension results. The tension of the ligaments and the close approximation of the flatter parts of the condyles make the erect position relatively easy to maintain.

The sequence of actions in flexion is reversed in

extension. Flexion can be carried through about 130 degrees and is finally

limited by contact between calf and thigh. The

muscles concerned in the movements at the knee are primarily thigh muscles.

There are three articulations in the knee—the

femoropatellar articulation and two femorotibial joints. The latter two are

separated by the intra-articular cruciate ligaments and the infrapatellar

synovial fold. The three joint cavities are connected by restricted openings.

The articular surfaces of the femur are its medial and

lateral condyles and the patellar surface, also known as the trochlea of the knee. The condyles are shaped like

thick rollers diverging inferiorly and posteriorly. Their surfaces gradually

change from a flatter curvature anteriorly to a tighter curvature posteriorly

and are separated from the patellar surface by a slight trochlear groove.

On the superior surface of the tibia, or the tibial

plateau, there are two separate, cartilage-covered areas. The surface of the

medial condyle is larger, oval, and slightly

concave; that of the lateral condyle is ap- proximately circular, concave from

side to side, but concavoconvex from before backward. The fossae of the

articular surfaces are deepened by disclike menisci. The composition and

morphology of the menisci make them important in distribution of load about the

knee during weight bearing.

|

| OSTEOLOGY OF THE KNEE |

The articular capsule of the knee joint is scarcely

separable from the ligaments and aponeuroses apposed to it. Posteriorly, its vertical fibers arise from the condyles and

intercondylar fossa of the femur; inferiorly, these fibers are overlain by the

oblique popliteal ligament. The capsule attaches to the tibial condyles and,

incompletely, to the menisci. The external ligaments reinforcing the capsule

are the fascia lata and the iliotibial tract; the medial patellar and lateral

patellar retinacula; and the patellar, oblique popliteal, and arcuate popliteal

ligaments. The medial (tibial) collateral ligament also closely reinforces the

capsule on the medial side.

The aponeurotic tendons of the vastus muscles attach

to the sides of the patella and then expand over the front and sides of the

capsule as the medial and lateral patellar retinacula. Below, they insert into

the front of the tibial condyles and into their oblique lines as far to the

sides as the collateral

ligaments. Superficially, the fascia lata overlies and blends with the

retinacula as it descends to attach to the tibial condyles and their oblique

lines. Laterally, the iliotibial tract curves forward over the lateral patellar

retinaculum and blends with the capsule anteriorly. Its posterior border is

free, and fat tends to be interposed between it and the capsule.

The patellar ligament is the continuation of the

quadriceps femoris tendon to the tuberosity of the tibia.

An extremely strong and relatively flat band, it

attaches above the patella and continues over its front with fibers of the

tendon, ending somewhat obliquely on the tibial tuberosity. A deep

infrapatellar bursa intervenes between the tendon and the bone. A large,

subcutaneous infrapatellar bursa is developed in the tissue over the ligament.

The oblique popliteal ligament is one of the

specializations of the tendon of the semimembranosus muscle, which

reinforces the posterior surface of the articular capsule. As this tendon

inserts into the groove on the posterior surface of the medial condyle of the

tibia, it sends this oblique expansion lateralward and superiorly across the

posterior aspect of the capsule.

KNEE: LATERAL AND MEDIAL VIEWS

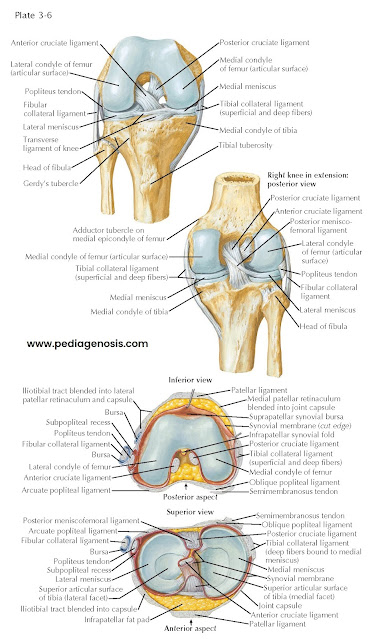

COLLATERAL LIGAMENTS

These ligaments prevent hyperextension of the joint

and any abduction-adduction angulation of the bones because they are essential

in resisting varus and valgus forces to the knee. Both collateral ligaments are

tighter in extension and progressively relaxed as the knee is brought into

flexion. The inferior genicular blood vessels pass between them and the capsule

of the joint, but only the lateral (fibular) collateral ligament stands clearly

away from the capsule.

The medial (tibial) collateral ligament is a strong,

flat band that extends between the medial condyles of the femur and tibia. It

can be broken down into superficial and deep layers that may be separated by a

thin bursa that facilitates the slight movement between these layers. The

medial collateral ligament (MCL) is well defined anteriorly, blending with the

medial patellar retinaculum. The pes

anserinus tendon overlies the ligament below, the two being separated by the

anserine bursa. The posterior portion of the ligament is characterized by

obliquely running fibers, which converge at the joint level from above and

below and give the ligament an attachment into the medial meniscus. The principal

inferior attachment of the ligament is about 5 cm below the tibial articular

surface immediately posterior to the insertion of pes anserinus.

The lateral (fibular) collateral ligament is a more

rounded, pencil-like cord, which is entirely separate from the capsule of the

knee joint. It is attached to a tubercle on the lateral condyle of the femur

above and behind the groove for the popliteus muscle. It ends below on the

lateral surface of the head of the fibula, about 1 cm anterior to its apex. The

tendon of the popliteus muscle passes deep to the ligament, and the biceps

femoris tendon divides around its fibular attachment, with a

small inferior subtendinous bursa intervening. Another bursa lies under the

upper end of the ligament, separating it from the popliteus tendon. The

synovial membrane of the joint, protruding as the subpopliteal recess,

separates the popliteus tendon from the lateral meniscus.

CRUCIATE LIGAMENTS

The cruciate ligaments prevent forward or backward

movement of the tibia under the femoral condyles. These ligaments also play a

large role in providing rotator stability about the knee joint. They are some-

what taut in all positions of flexion but become tightest in full extension and

full flexion. They lie within the capsule of the knee joint, in the vertical

plane between the condyles, but are excluded from the synovial cavity by

coverings of synovial membrane. Both ligaments spread linearly at their bony

attachments, especially at the femoral condyles.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) arises from the

rough, nonarticular area in front of the intercondylar eminence of the tibia

and extends upward and backward to the posterior part of the medial aspect of

the lateral femoral condyle. The

ACL can be divided into an anteromedial bundle and a posterolateral bundle. The

anteromedial bundle is tight in flexion, and the posterolateral bundle is tight

in extension.

The thicker and stronger posterior cruciate ligament

(PCL) passes upward and forward on the medial side of the anterior ligament. It

extends from an extra-articular attachment over the back of the tibial plateau

to the lateral side of the medial condyle of the femur. The PCL also consists

of an anterolateral bundle and a posteromedial

bundle. The posteromedial bundle is tight in extension, and the anterolateral

band is tight in flexion. Both ligaments receive their primary blood supply

from the medial genicular artery and their innervations from branches off the

tibial nerve.

|

| KNEE: POSTERIOR AND SAGITTAL VIEWS |

MENISCI

These crescent-shaped wafers of fibrocartilage sur-

mount the peripheral parts of the articular surfaces of the tibia. Thicker at their external margins and tapering to thin,

unattached edges in the interior of the articulation, they deepen the articular

fossae for the reception of the femoral condyles. They are attached to the

outer borders of the condyles of the tibia and at their ends, anterior and

posterior, to its intercondylar eminence.

The medial meniscus is larger and more nearly oval in

outline. Broader posteriorly, it narrows anteriorly as it attaches in the

intercondylar area of the tibia in front of the origin of the PCL. The lateral

meniscus is more nearly circular. Although smaller than the medial meniscus, it

covers a somewhat greater proportion of the tibial surface. Anteriorly, it

attaches in the anterior intercondylar area, lateral to and behind the end of

the ACL. Posteriorly, it ends in the posterior intercondylar area in front of

the end of the medial meniscus. The medial meniscus is also attached to the

MCL, making it significantly less mobile than the lateral meniscus. The lateral

meniscus is weakly attached around the margin of the lateral tibial condyle and

lacks an attachment where it is crossed and notched by the popliteus tendon. At

the back of the joint, it gives origin to some of the fibers of the popliteus

muscle; and close to its posterior attachment to the tibia, it frequently gives

off a collection of fibers, known as the posterior menisco- femoral ligament.

This may join the PCL or may insert into the medial femoral condyle behind the

attachment of the PCL. An occasional anterior meniscofemoral ligament has a

similar but anterior relationship to the PCL. The transverse ligament of the

knee connects the anterior convex margin of the lateral meniscus to the

anterior end of the medial meniscus.

The blood supply to the medial and lateral menisci

come from the superior and inferior branches of the medial and lateral

geniculate arteries, respectively. There are three commonly referred to zones

of the menisci based on their respective blood supply. Starting from the most

vascularized peripheral (outermost) portion of the meniscus, these are the

red-red, red- white, and white-white zones. These zones play a large role in

therapeutic decision making owing to the

role that increased vascularity will play in the likelihood of healing.

Vascularity is also variable among patients of different ages, because you ger

patients tend to have a more robust

blood supply.

KNEE: INTERIOR VIEW AND CRUCIATE AND COLLATERAL LIGAMENTS

SYNOVIAL MEMBRANE AND

JOINT CAVITY

The articular cavity of the knee is the largest joint

space of the body. It includes the space between and around the condyles,

extends upward behind the patella to include the femoropatellar articulation,

and then communicates freely with the suprapatellar bursa between the

quadriceps femoris tendon and the femur. The synovial membrane lines the

articular capsule and the suprapatellar bursa. Recesses of the joint cavity are

also lined by synovial membrane; the subpopliteal recess has been described.

Other recesses exist behind the posterior part of each femoral condyle; at the

upper end of the medial recess, the bursa under the medial head of the

gastrocnemius muscle may open into the joint cavity.

The infrapatellar fat body or pad represents an

anterior part of the median septum, which, with the cruciate ligaments,

separates the two femorotibial articulations. From the medial and lateral

borders of the articular surface of the patella, reduplications of synovial

mem- brane project into the interior of the joint and form two fringelike alar

folds, which cover collections of fat. The fat pad is a normal structure but in

many cases it may become inflamed or impinge within the patella and femoral condyle

and become problematic.

BLOOD VESSELS AND NERVES

In the region of the knee there is an important

genicular anastomosis. This consists of a superficial plexus above and below

the patella, plus a deep plexus on the capsule of the knee joint and the adjacent

bony surfaces. The anastomosis is made up of terminal interconnections of 10

vessels. Two of these descend into the joint—the descending branch of the

lateral circumflex femoral artery and the descending genicular branch of the

femoral artery. Five are branches of the popliteal artery at the level of the

knee—the medial superior genicular, lateral superior genicular, middle

genicular, medial inferior genicular, and lateral inferior genicular arteries.

Three branches of leg arteries ascend to the anastomosis—the posterior tibial

recurrent, circumflex fibular, and anterior tibial recurrent arteries. Veins of

the same names accompany the arteries. The lymphatics of the knee joint drain

to the popliteal and inguinal node groups.

The nerves of the knee joint are numerous.

Articular branches of the femoral nerve reach the knee via the nerves to the

vastus muscles and the saphenous nerve. The posterior division of the obturator

nerve ends in the joint, and there are also articular branches of the tibial

and common peroneal nerves.

PATELLA

The large sesamoid is developed in the tendon of the

quadriceps femoris muscle. It bears against the anterior articular surface of

the inferior extremity of the femur and, by holding the tendon off the lower

end of the femur, improves the angle of approach to the tendon to the tibial

tuberosity. The convex anterior surface of the patella is striated vertically

by the tendon fibers. The superior border is thick, giving attachment to the

tendinous fibers of the rectus femoris and vastus intermedius muscles. The

lateral and medial borders are thinner; they receive the fibers of the vastus

lateralis and vastus medialis muscles. These borders converge to the pointed

apex of the patella, which gives attachment to the patellar ligament. The articular surface is a smooth oval area,

divided by a vertical ridge into two facets. The ridge occupies the groove on

the patellar surface of the femur, the medial and lateral facets corresponding

to facing surfaces of the femur. The lateral facet is broader and deeper than

the medial. Inferior to the faceted area is a rough nonarticular portion from

which the lower half of the patella ligament arises.

The patella maintains a shifting contact with the

femur in all positions of the knee. As the knee shifts from a fully flexed to a fully extended position, first the superior,

then the middle, and lastly the inferior parts of the articular surface of the

patella are brought into contact with the patellar surfaces of the femur. The

largest amount of contact between the patella and the trochlea is at about 45

degrees of knee flexion.

Ossification develops from a single center, which appears early in the third year of life. Complete ossification occurs by age 13 in the male and at about age 10 in the female.