Anatomic

Relationships of the Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus is a small

area, weighing about 4 g of the total 1,400 g of adult brain weight, but it is

the only 4 g of brain without which life itself is impossible. The hypothalamus

is so critical for life because it contains the integrative circuitry that

coordinates autonomic, endocrine, and behavioral responses that are necessary

for basic life functions, such as thermoregulation, control of electrolyte and

fluid balance, feeding and metabolism, responses to stress, and reproduction.

|

| ANATOMY AND RELATIONS OF THE HYPOTHALAMUS AND PITUITARY GLAND |

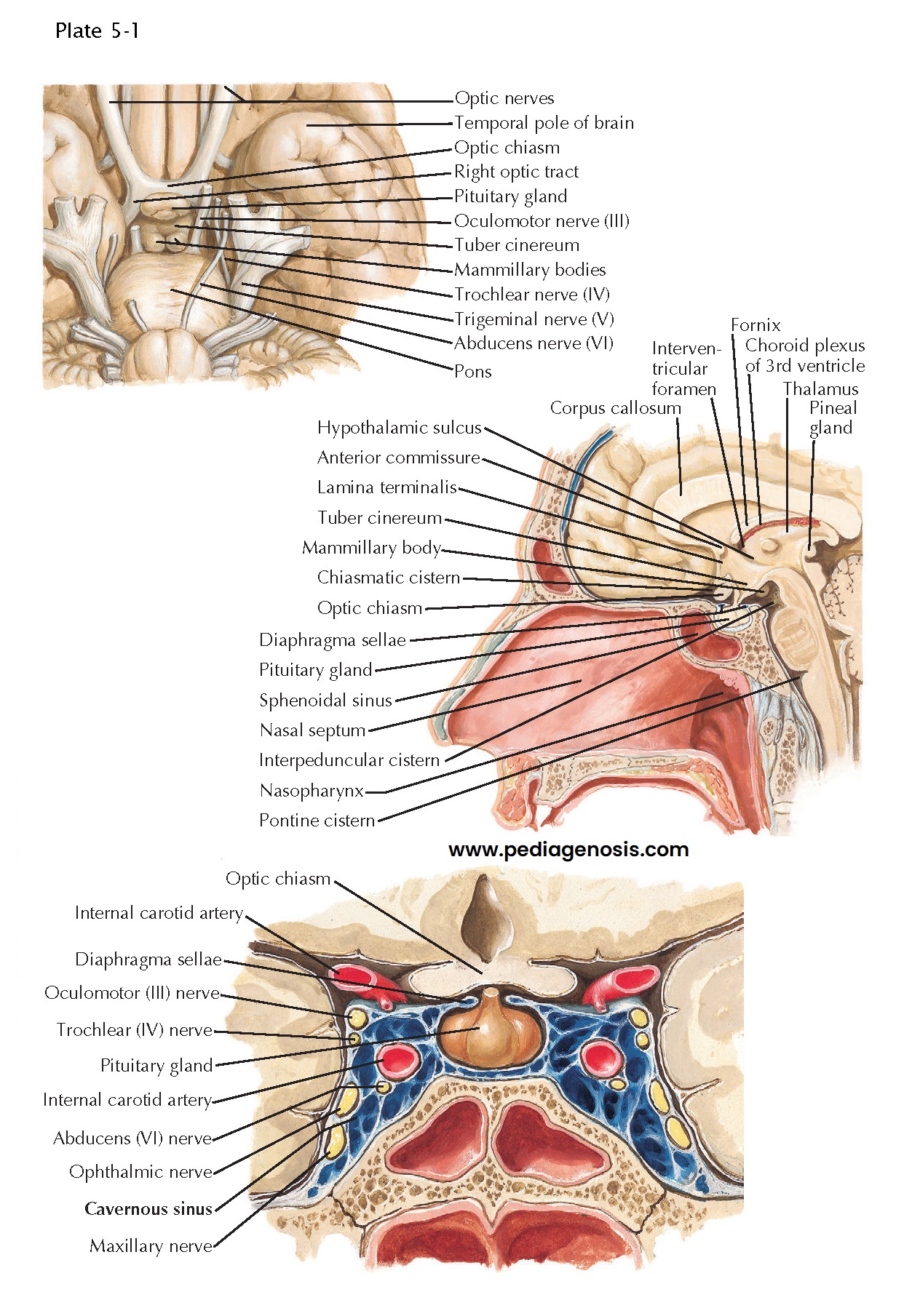

Perhaps for this reason, the hypothalamus is particularly well protected. It lies at the base of the skull, just above the pituitary gland, to which it is attached by the infundibulum, or pituitary stalk. As a result, trauma that affects the hypothalamus would almost always be lethal. It receives its blood supply directly from the circle of Willis (see Plate 5-3), so it is rarely compromised by stroke, and it is bilaterally reduplicated, with survival of either side being sufficient to sustain normal life.

On the other

hand, the hypothalamus may be involved by a number of pathologic processes that

arise from structures that surround it, and the signs and symptoms that first

attract attention in those disorders are often due to the involvement of those

neighboring structures. Examination of the ventral surface of the brain shows

that the hypothalamus is framed by fiber tracts. The optic chiasm marks the

rostral extent of the hypothalamus, and the optic tracts and cerebral peduncles

identify its lateral borders. The pituitary stalk emerges from the midportion

of the hypothalamus, sometimes called the tuber cinereum (gray swelling), just

caudal to the optic chiasm. As a result, tumors of the pituitary gland, which

are among the more common causes of hypothalamic dysfunction, typically involve

the optic chiasm (producing bitemporal visual field defects) or the optic

tracts as an early sign.

The posterior

part of the hypothalamus is defined by the mammillary bodies, which are

bordered caudally by the interpeduncular cistern, from which emerge the

oculomotor nerves. These are joined in the cavernous sinus, which runs just

below the hypothalamus and lateral to the pituitary gland, by the trochlear and

abducens nerves. Hence pathologies such as aneurysms of the internal carotid

artery or infection or thrombosis of the cavernous sinus, which may impinge on

the hypo- thalamus, typically involve the nerves controlling eye movements at

an early stage. If there is a mass of suf- ficient size, it may also involve

the trigeminal nerve. The ophthalmic division, which traverses the cavernous

sinus, is most commonly involved, but if the mass is large enough and

posteriorly located, it can involve the maxillary or even the mandibular

division of the trigeminal nerve as well. Just lateral to the cavernous sinus

sits the medial temporal lobe. As a result, pathology in this area can also

cause seizures, most commonly of the complex partial type, with loss of

awareness for a brief period.

In the midline, the hypothalamus borders the ventral part of the third ventricle. The supraoptic recess of the third ventricle, which surmounts the optic chiasm, ends at the lamina terminalis, the anterior wall of the ventricle. This is the most anterior part of the diencephalon in the developing brain. The infundibular recess defines the floor of the hypothalamus that overlies the pituitary stalk. This portion of the hypothalamus is called the median eminence and is the site at which hypothalamic releasing hormones are secreted into the pituitary portal circulation (see Plate 5-3).