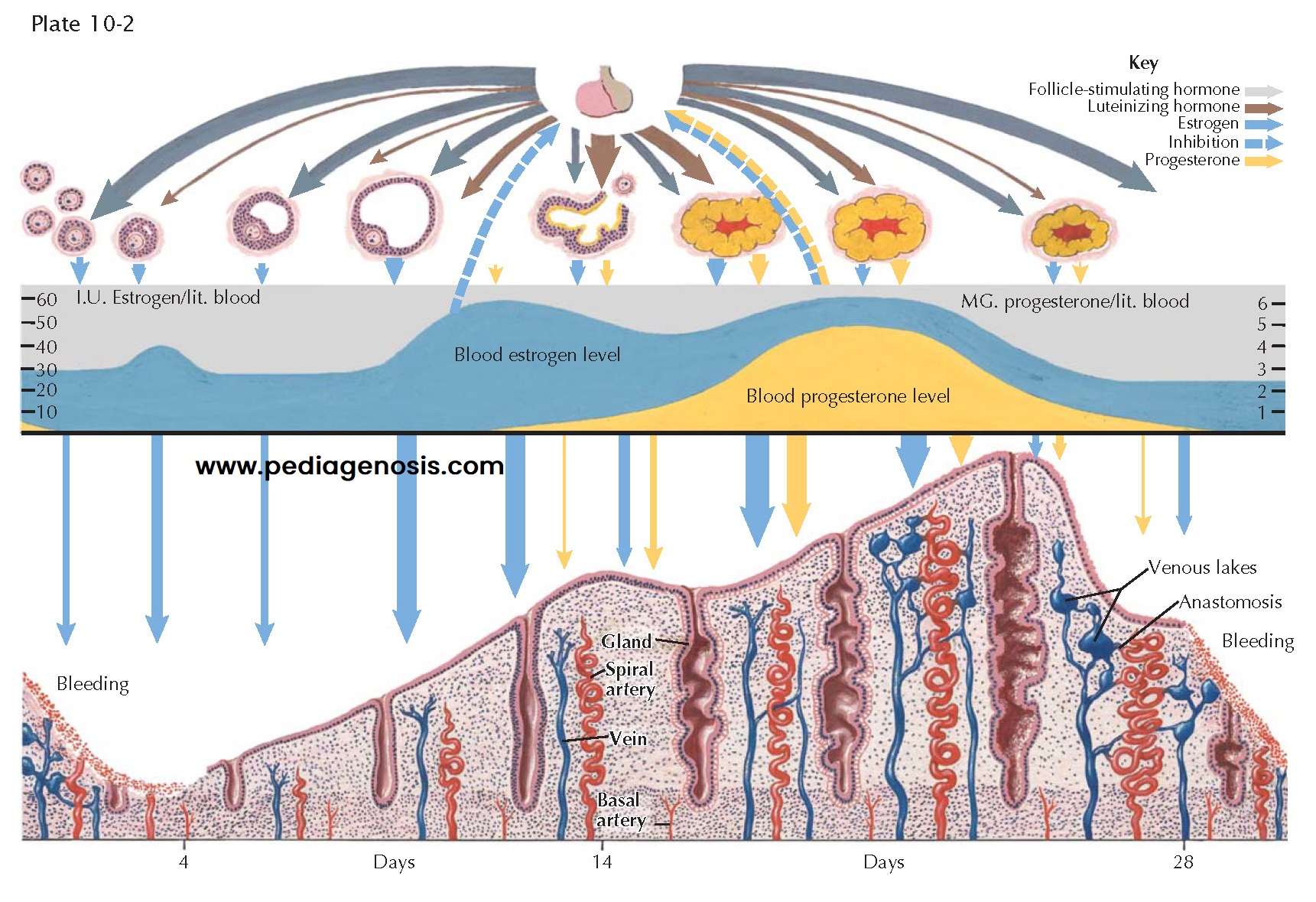

ENDOCRINE RELATIONS DURING CYCLE

Menarche, or the

first menstrual cycle, heralds the onset of adult reproductive function, which

continues until menopause, when the major part of ovarian function ceases.

Between these events, the hormonal ballet of cyclic menstruation takes place.

Two anterior pituitary gonadotropins and two ovarian steroids are primarily involved in this periodic occurrence of menstruation: the pituitary contributes follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), whereas the ovary secretes-estradiol and progesterone.

Up to puberty—even during fetal life—ovarian follicles are constantly

developing to a stage in which an antrum has formed, regressing then to become

atretic. Eventually, one or more follicles produce enough estrogen to cause a

proliferation of the endometrium. It is unlikely that any of these early

follicles, though producing estrogen, achieve ovulation; more likely, atresia

sets in and the endometrium breaks down, with resultant bleeding. It is

probable that the mature cycle will not become established for several months

after this, the first menstruation.

At the onset of menstrual flow (day 1), production of estrogen is low but

FSH levels rise and initiate another round of folliculogenesis. A cohort

consisting of a number of follicles begins the maturation process approximately

375 days prior to day 1 of the menstrual cycle. By the onset of menses, these

have matured enough to respond with growth and an increase in estrogen. Most of

the follicles, however, have a relatively short life. Their granulosa cells and

ovum degenerate, leaving an atretic follicle. A few continue to enlarge, but in

most cycles only one emerges as the mature graafian follicle that ruptures or

ovulates about day 14.

Through about day 12 of the cycle, the secretion of FSH decreases with

the increase of estrogen production. Although follicle growth beyond the stage

of antrum formation must be initiated by the pituitary and continues to be

dependent on this stimulus for the first week or so of the cycle, after about

day 8 further development is autonomous. A surge of LH (and to a lesser extent

FSH) at midcycle reflects this rising estrogenic tide and it provides the

endocrine trigger for ovulation.

After ovulation the estrogen level drops slightly during a lag period

between the functional peak of the mature follicle and that of the fully

developed corpus luteum. Some uterine spotting or even bleeding for a day or

two is not rare at this time (“midcycle bleeding”).

Within a few hours after ovulation, the empty cavity of the ruptured

follicle becomes filled with blood clots, and a network of capillary fingers

stretches tentatively inward along fibrin strands from the theca interna. Theca

cells containing a yellow lipochrome, named lutein, proliferate centripetally

at a rapid rate along with the capillary mesh. Progesterone production is

quickly accelerated, and its effect can be detected by secretory changes in the

endometrium within 48 hours after ovulation.

Stimulation of the thermal center in the brainstem, by progesterone,

causes a rise in basal body temperature, which is sustained as long as the

corpus luteum functions. Cervical mucus becomes scanty and viscid and, when

rapidly dried on a slide, no longer crystallizes in a “fernlike” pattern. By

day 20, the estrogen level is usually as high as that just before ovulation,

and the corpus luteum has also reached a peak of production of progesterone.

Under the influence of estrogen and progesterone, growth and the secretory activity of the endometrium progress continuously through day 25 or 26. Unless fertilization has occurred, degeneration of the corpus luteum is initiated. With the consequent decline of both estrogen and progesterone, changes occur in the endo- metrium that lead inevitably to slough and necrosis. By day 28, the pituitary, now released from the inhibitive levels of estrogen, starts again and rapidly reaches its peak of FSH output, which supports a new crop of primary follicles for the next cycle.