CONTRACEPTION

Few capabilities have had the wide-reaching social

implications than that of the ability to control fertility. Changing patterns of

sexual expression, new technologies, increased consumerism, and heightened cost

pressures all affect the choices made in the search for fertility control.

In the United States, about half (49%) of all pregnancies are unplanned, despite the fact that 90% of women at risk (fertile, sexually active, and neither pregnant nor seeking pregnancy) are using some form of contraception. The 10% or so of women not using contraception account for more than half of these unintended pregnancies. The remaining unplanned pregnancies occur as a result of either failure of the contraceptive method used or the improper or inconsistent use of the method. There is no “ideal” contraceptive method. Although efficacy and an acceptable risk of side effects are impor- tant in the choice of contraceptive methods, these are often not the factors upon which the final choice is made. Motivation to use, or continuing to use, a contraceptive method is based on education, cultural background, cost, and individual needs, preferences, and prejudices. Factors such as availability, cost, coital dependence, personal acceptability, and the patient’s perception of the risk all have a role in the final choice of methods. For a couple to use a method, it must be accessible, immediately available (especially in coitally dependent or “use-oriented” methods), and of reasonable cost. The impact of a method on spontaneity or the modes of sexual expression preferred by the patient and her partner may also be important considerations.

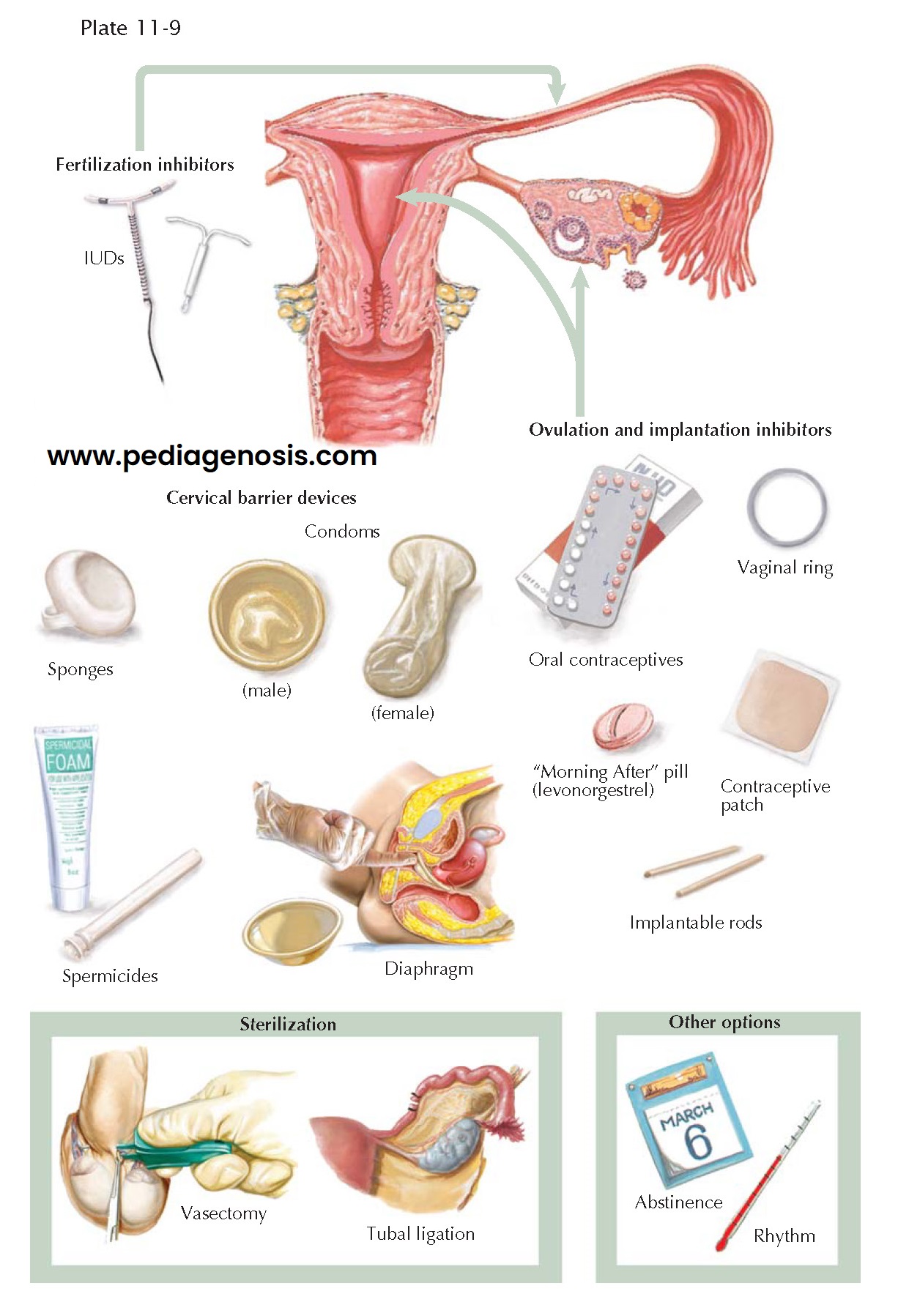

Currently available contraceptive methods seek to prevent pregnancy by preventing

the sperm and egg from uniting or by preventing implantation of the embryo that

results from the fertilized egg. Most contraceptive methods have multiple possible

mechanisms of action. For example, hormonal contraceptives, including postcoital

contraceptives, work primarily by preventing the development and release of the

egg but, if ovulation occurs, may affect the likelihood of either the sperm and

egg uniting or reducing the likelihood of implantation. Copper intrauterine devices,

by contrast, work primarily through a toxic effect on sperm and egg; in the event

of fertilization, however, the likelihood of implantation is decreased. By contrast,

barrier contraceptives, including mechanical barriers such as male and female condoms;

chemical barriers such as spermicides; and temporal barriers such as withdrawal

and fertility awareness methods (e.g., rhythm method) work exclusively by preventing

union of the sperm and egg.

Adolescent patients require reliable contraception, but often have problems

with compliance. Careful counseling about options (including abstinence), the

risks of pregnancy and sexually transmitted disease, as well as the need for both

contraception and disease protection must be provided. These patients may be

better served by methods that rely less on the user for reliability (intrauterine

contraceptive devices [IUCDs] or long-acting hormonal agents such as injections,

ring, patches, and implants) than those that depend on consistent use (use-oriented

methods and those that are very time sensitive such as progestin-only oral

contraceptives).

Patients over the age of 35 may continue to use low-dose oral contraceptives

if they have no other risk factors and do not smoke. Compliance concerns are generally

less in these patients, making use-oriented methods more acceptable and reliable.

Long-term methods (IUCDs, long-acting progesterone contraception, or sterilization)

may also be appropriate. Until menopause is confirmed by clinical or laboratory methods,

contraception must be continued.

When unprotected intercourse occurs, pregnancy interdiction can often be achieved by the use of high-dose progestins (2 to 0.75 mg levonorgestrel tablets given up to 120 hours after intercourse) or the placement of a copper-bearing IUCD (up to 10 days after midcycle intercourse).