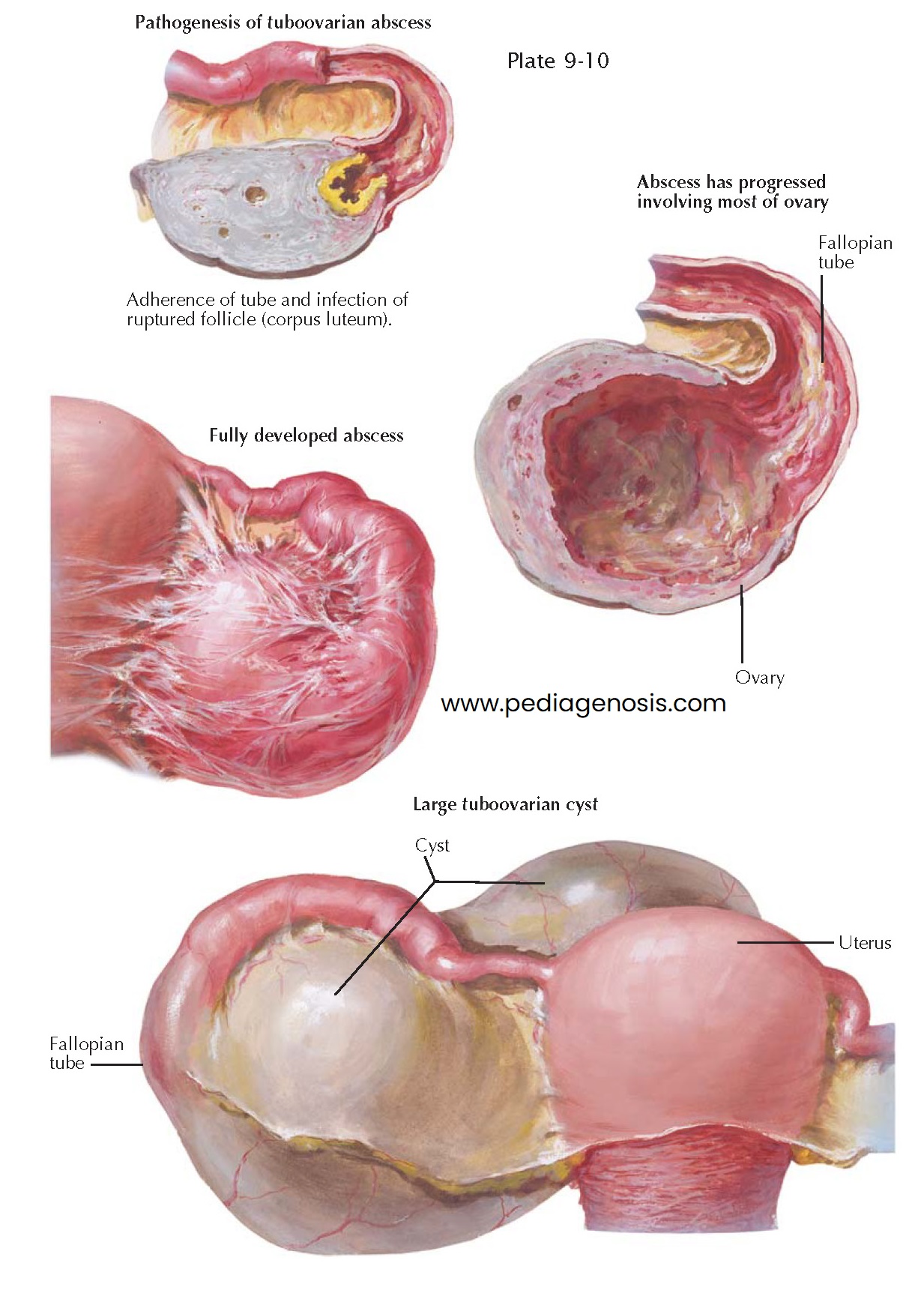

TUBOOVARIAN ABSCESS

Occasionally, a pyosalpinx communicates

with a ruptured follicle or a corpus luteum, leading to a tubo-ovarian abscess.

Combined lesions of the fallopian tubes and the ovaries are, however, not limited

to this particular formation, but they are the rule in all tubal inflammations. The

ovary may be the site of true bacterial inflammation or may merely be involved in

a circulatory disorder and degenerative changes arising from the inflammation of

the neighboring tube. The latter changes consist of hyperemia, hemorrhages, and

edema of the ovarian stroma, disintegration of the follicular apparatus, loss of

surface epithelium, and formation of periovarian adhesions.

The bacterial inflammation may be slight and may heal in the course of time, with or without fibrosis of the ovarian parenchyma, or it may be severe and may result in the formation of abscesses, which may develop in ruptured follicles or in corpora lutea or within the ovarian connective tissue. The follicular and luteal abscesses occur usually when the infection takes place on the surface of the ovary, as is the case in purulent salpingitis or appendicitis. Abscesses in the ovarian stroma are often of hematogenic origin and may remain within the limits of the ovary, though they may reach a large size. Sometimes, however, they burst into the tube or into the peritoneal cavity or a neighboring organ, such as the rectum or the bladder.

Gradually, the follicular components and the specific ovarian stroma are completely

destroyed in such ovaries, and the thick wall of the ovarian abscess consists merely

of callous connective tissue which is poor in blood vessels and is infiltrated by

leukocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, which are accumulated in the inner, granulating

lining of the abscess wall.

Follicular and corpus luteum abscesses more often perforate into the tube

than do interstitial ovarian abscesses. They may heal after discharging their content

into the tube or may be transformed into tuboovarian abscesses, with progressive

destruction of the ovarian parenchyma. Ovarian and tuboovarian abscesses have

little tendency to spontaneous healing because of the thickness of their walls.

However, intravenous administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics may result in

resolution of the infection. When medical treatment fails, surgical management is

required. They can be emptied either from the posterior vaginal fornix or from

the abdomen if they are large, and can be reached in this way without exposing the

free peritoneal cavity to contamination with the purulent content of the

abscess. A definite cure can, however, be achieved only by complete removal of the

diseased adnexa, usually in connection with the uterus.

In rare instances, a tuboovarian abscess may finally change into a tuboovarian cyst. The latter is a retort-like formation consisting of the dilated tube, which communicates with a unilocular ovarian cyst. As a rule, the tuboovarian cyst contains clear serous fluid but at times also some red blood cells and leukocytes. On its inner surface, the transition between the tube and the ovary is often indicated by a sharp ring through which the flattened fimbriae pass into the ovarian cyst, spread- ing in the form of low ridges in its wall. In other cases, no demarcation between tubal and ovarian tissues is recognizable macroscopically. All, or almost all, tuboovarian cysts are of inflammatory origin, though a few result from true tuboovarian abscesses. In most cases, they originate from the union of a hydrosalpinx and a retention cyst or a seropapillary ovarian cyst. As a rule, the tuboovarian cyst is a benign structure, changing very little in the course of time. Only in rare cases does a cancer develop in a tuboovarian cyst. Because of the impact of both the tuboovarian cyst and the processes that lead to it, symptoms of pain, subfecundity, or recurrent infections may precipitate the need for surgical intervention.