TUBERCULOSIS

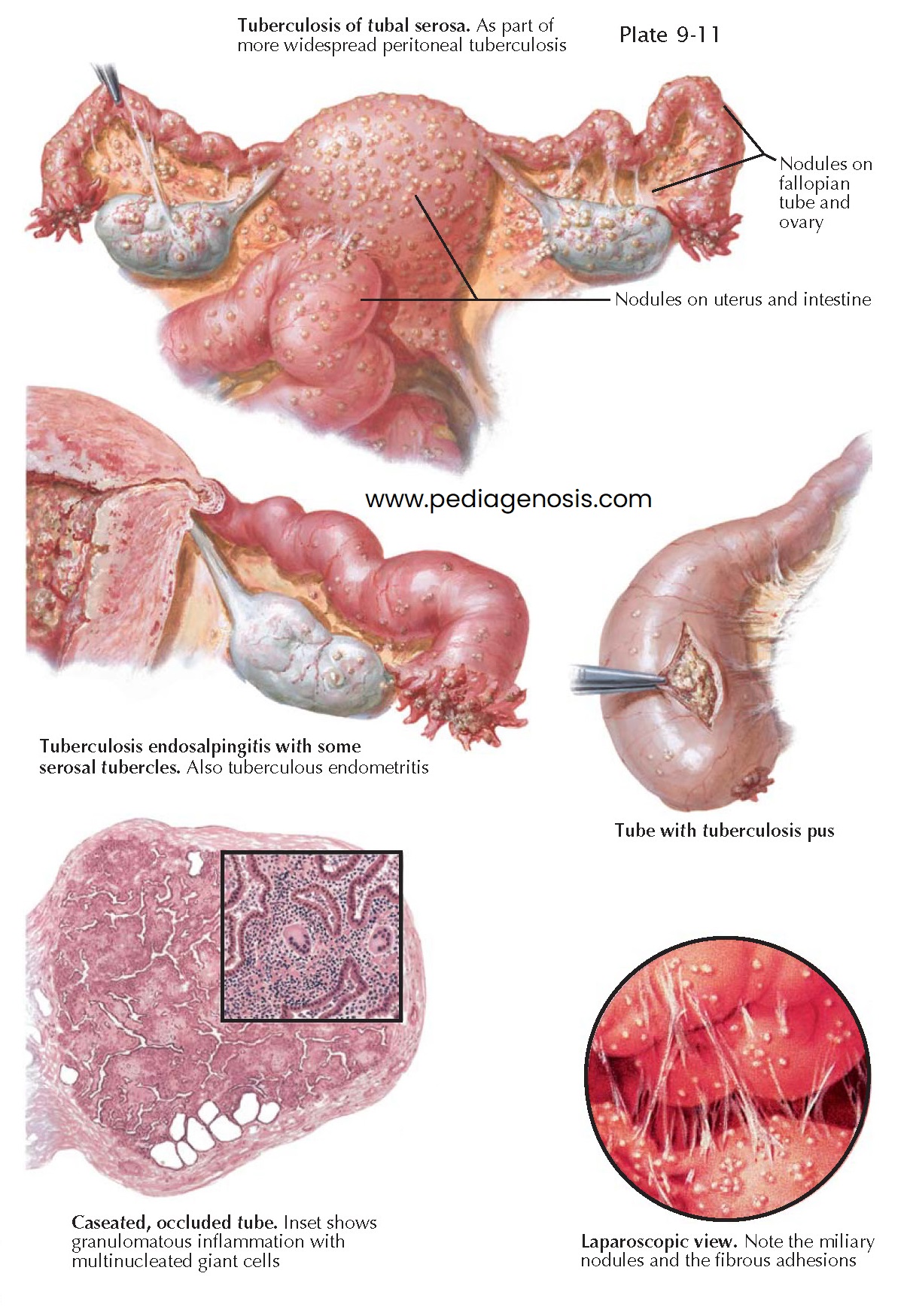

At one time, about 10% of all inflammatory disease of the tubes was tuberculous. Tuberculosis of the upper genital tract, primarily chronic salpingitis and chronic endometritis, is now a rare disease in the United States. However, pulmonary tuberculosis is steadily increasing in the United States, and with this rise it is likely that the incidence of pelvic tuberculosis also will increase. Tuberculosis is a frequent cause of chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility in other parts of the world and may be encountered in immigrants, especially those from Asia, the Middle East, and Latin America. Genital tuberculosis may occur at any age but is most often encountered in women between 20 and 30 years old, though it will occur in postmenopausal women 10% of the time. Both tubes almost always are involved in the tuberculous disease, whereas the uterus is affected in slightly more than 50%. The other reproductive organs are only rarely involved.

As a rule, the infection is carried to the tubes by the hematogenous route

from a primary focus in the lung or the hilar lymph nodes. Early in the course of

pulmonary infection, the bacteria spread and the infection becomes located in the

tubes, and from there the bacilli usually spread to the endometrium and less commonly

to the ovaries. Despite these possible coinfections, the oviducts are the primary

and predominant site of pelvic tuberculosis. Pelvic tuberculosis may be produced

by either Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium bovis. The focus

may be quite small and insignificant and may not cause any clinical symptoms. However,

in the majority of cases, it is impossible to determine whether the infection has

spread from the peritoneum to the tube or from the tube to the peritoneum. The possibility

of an infection of the tubes by intracavitary or lymphatic ascent of tubercle bacilli

introduced into the vagina by coitus with a tuberculous male cannot be denied.

However, this mode of infection is extremely rare.

Changes in the fallopian tube as a result of an infec- tion with tubercle

varies to a great extent. In the initial stages, the tubal mucosa may be studded

with miliary tubercles. In women with tuberculous peritonitis, the serosa of the

tubes, as well as the surfaces of the uterus and the ovaries, is dotted with small

tuberculous nodules. In more advanced cases of tuberculous endosalpingitis, the

miliary nodules coalesce to form an exudate that also infiltrates the outer layers

of the tube, causing marked thickening of the tubal wall. Because the tuberculous

process occurs in separate foci and not diffusely, the tube appears nodular (“rosary”

form), with increased sinuosity. The infiltrate may undergo caseous necrosis, producing

a pyosalpinx filled with caseous purulent material. In more favorable cases, the

granulation tissue may become fibrotic, shrunken, and calcified.

The diagnosis of genital tuberculosis is difficult in most cases. The patients

quite frequently complain in a rather vague fashion only about amenorrhea and a

dull pain in the lower abdomen (35% of cases); they sometimes request medical advice

only because of sterility. Suspicious signs of genital tuberculosis are as

follows: slow, insidious development of adnexal tumors; without any history, signs

or symptoms of gonorrhea or operative infection; palpable nodules in the cul-de-sac;

rosary-type thickening of the tubes; moderate deviations of temperature; and lymphocytosis.

The findings at pelvic examination are normal in approxi-mately 50% of cases. An

endometrial biopsy, probatory curettage, or the demonstration of tubercle bacilli

in the uterine secretions gives evidence of tuberculous genital infection. Differentiation

of tubercle bacilli requires culture.

The course of the disease becomes stormy if diffuse peritonitis intervenes or if a caseous pyosalpinx becomes secondarily infected by pyogenic bacteria. The course of the infection may be one of either an insidious or a rapidly progressing disease.