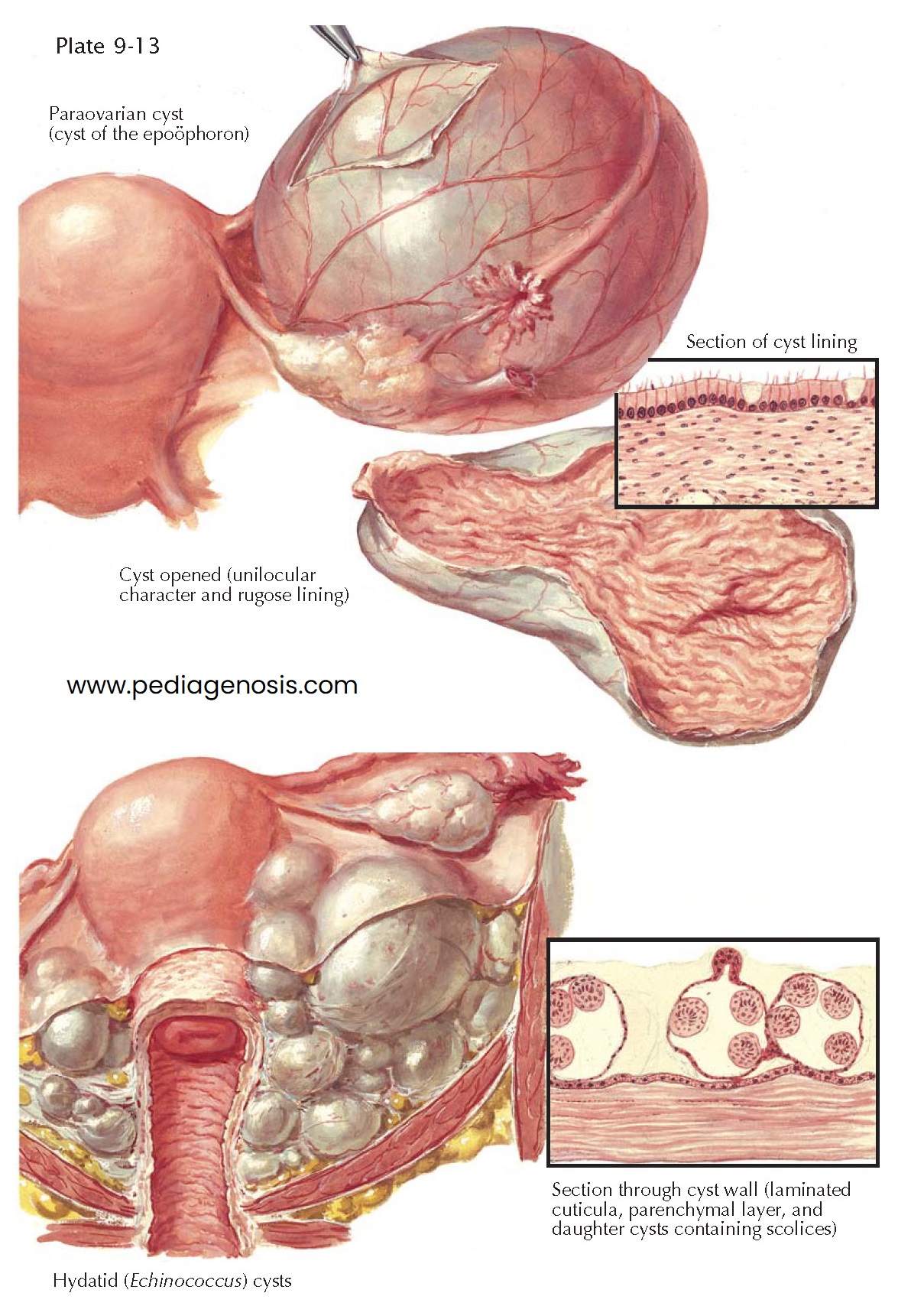

PARAOVARIAN OR EPOÖPHORON CYST

Mesonephric cysts can

develop from the permanent portion of the mesonephron, which is the paraovarian

or epoöphoron, or from the inconstant residue of the wolffian (Gartner) duct. The

former, called paraovarian or epoöphoron cysts, may be small and may represent

simple retention cysts; some, however, are true blastomas, which grow continuously

and may finally attain an enormous size. As a rule, even the giant cysts remain

unilocular.

Owing to the intraligamentary location of the epoöphoron, the paraovarian cysts are always intraligamentary and are covered by the distended peritoneum of the broad ligament. Exceptionally, the cyst is fixed to its surroundings by dense inflammatory adhesions or, instead of expanding upward toward the peritoneal cavity, it may grow downward toward the pelvic floor or into the mesosigmoid.

The tube and the ovary are displaced and stretched out by the cyst. As a rule,

the tube encircles the tumor by running around it from the anterior to the posterior

surface of the cyst, where it reaches the flattened and elongated ovary with its

fimbriated end.

Paraovarian cysts do not have true pedicles, but if they continue to project

into the peritoneal cavity, some kind of pedicle develops; this consists of the

tube, the proper ovarian ligament, and the suspensory ligaments. Torsion of this

pedicle is by no means rare.

The wall of the epoöphoron cyst is usually thin and flaccid. It consists of

a dense, lamellated outer and a loose, reticular inner layer of connective tissue

and an innermost single-layered epithelial lining. The connective tissue is intermingled

with elastic fibers and sparse smooth muscle fibers. The epithelium is low in some

places and cylindrical and ciliated in others. In most cases the inner surface is

smooth but often becomes corrugated when the cyst is opened and emptied. The

rugose appearance of the cyst wall is due to the retractability of its elastic constituents.

Sometimes the inner surface of the cyst is puckered, and in isolated cases even

studded with papillary, cauliflower-like excrescences. As a rule, paraovarian cysts

are benign. Malignant degeneration is exceedingly rare.

In all cases of cysts situated in the broad ligament or in the deeper pelvic

connective tissue, the possibility of Echinococcus cysts should be taken

into consideration. Echinococcus cysts represent a rare hydatid form of Taenia

echinococcus, which is a tapeworm living in the intestine of various animals,

notably dogs and sheep. The disease is sporadic in the United States but common

in Australia, Iceland, Argentina, and some parts of Germany and Russia. Having arrived

in the human intestine, the oncospheres lose their sheaths, pierce the intestinal

wall with their hooklets, and pen- etrate into the bloodstream either directly or

by way of the lymphatics. They settle most commonly in the liver and lungs but occasionally

also in the pelvic connective tissue, where the oncospheres develop into cherry-to

head-sized cysts which are filled with clear fluid of low specific gravity (1.010 to

1.015). The wall of the cyst consists of an outer lamellar cuticle and an inner

granular parenchymal layer. From the latter, daughter cysts develop, as well as

budlike structures, the scolices, each provided with a crown of hooklets and two

lateral suckers.

In the pelvic connective tissue, the cysts are usually multiple because of

an exogenous proliferation of a single original cyst or because of a primary infection

with multiple oncospheres. A membrane of inflammatory connective tissue containing

lymphocytes and leukocytes, particularly numerous eosinophils, surrounds the cysts.

The treatment is surgical. Only complete removal of all cysts prevents recurrence. Opening the cysts and spilling their contents must be avoided.