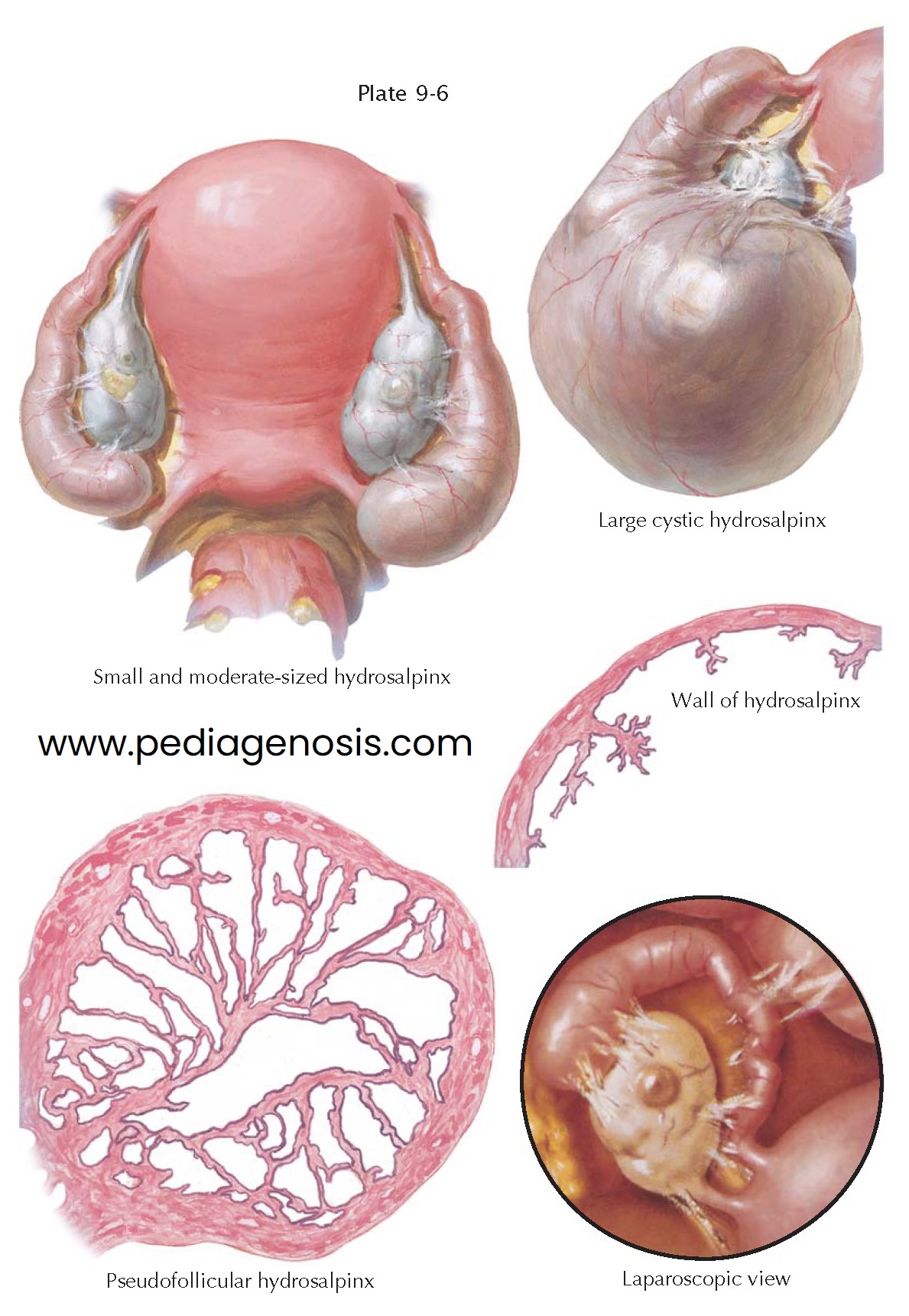

HYDROSALPINX

Recurrent or chronic adnexal infections may result

in a cystic dilation of the fallopian tube (hydrosalpinx), which may present as

an adnexal mass. The purulent contents of the pyosalpinx may thicken and gradually

be replaced by granulation tissue, which is sometimes calcified and, in rare instances,

even ossified. More often, however, the solid constituents of the tubal contents are gradually liquefied and changed into a serous or serosanguineous fluid,

thus transforming the pyosalpinx into a hydrosalpinx.

After resorption of the inflammatory infiltrate and the degenerated tissue, the tubal wall becomes thin and poor in muscle fibers and assumes a translucent appear- ance. The size of the hydrosalpinx can vary from twice that of a normal tube to that of a large sausagelike creation 3 cm or more in diameter, which, in form, has completely lost all resemblance to the tube from which it derived. The fimbriae in such a hydrosalpinx may have completely disappeared.

In cross sections, the mucosal folds are low and separated from each other

by flat areas. Sometimes the folds are completely effaced and are indicated only

by flat ridges or are not recognizable at all.

This form of hydrosalpinx (sometimes referred to as hydrosalpinx simplex)

may develop over a period of many years without causing any symptoms that would

prompt a woman to seek medical attention. This is understandable, because microscopically

this thin-walled cavity may appear to have lost all evidence of the originally infectious

and inflammatory process. In other instances, foci of a chronic inflammation can be

found in the tubal wall. As a rule, however, microorganisms cannot be cultured from

the cystic fluid.

The same holds true for the pseudofollicular hydrosalpinx, which differs from

the simplex type only in its cross section. Here the tubal folds may have been preserved

to a certain extent but have grown together at their opposing ridges and branches,

forming a labyrinth of hollow spaces. This pseudofollicular hydrosalpinx is

said to be most often the result of gonorrheal infection but may also be encountered

in chronic salpingitis of other origin.

The occlusion of the tube on its uterine end is not always tight. In rare

cases, the tubal lumen is blocked in this section only by valvelike folds and may

open if the hydrosalpinx becomes distended. This condition, which is characterized

by the periodic escape of tubal contents and accompanied by colicky pain, is called

“hydrops tubae profluens.”

In hydrosalpinx, the peritubal adhesions are often few and filmy, and hence

torsion of an oviduct is no rare occurrence. Extravasation of blood into the twisted

tube changes the hydrosalpinx into a hematosalpinx.

The diagnosis of hydrosalpinx, and incidentally also of pyosalpinx, is not

always an easy one. They may be mistaken, particularly if they are very large, for

ovarian cysts, although the latter are more movable. Laboratory pregnancy tests

may prove useful in the differentiation from ectopic pregnancy. From a cooperative

patient, one will always obtain a history of a past acute episode of pelvic infection,

which, with the findings of the physical examination, will lead to the correct

diagnosis. Although a patient may report a history of a past acute episode, the

history of pelvic infection is usually not volunteered.

Surgical therapy for a hydrosalpinx (salpingectomy or salpingo-oöphorectomy) is curative. Neosalpingostomy may be considered when fertility is to be maintained, but the success of this procedure is inversely proportional to the size of the hydrosalpinx and is generally less than 15%. More often, in vitro fertilization, bypassing the damaged tubes, is recommended, though the success rates are lower in these patients. Prior to in vitro fertilization, removal of the affected hy rosalpinx improves implantation and pregnancy rates.