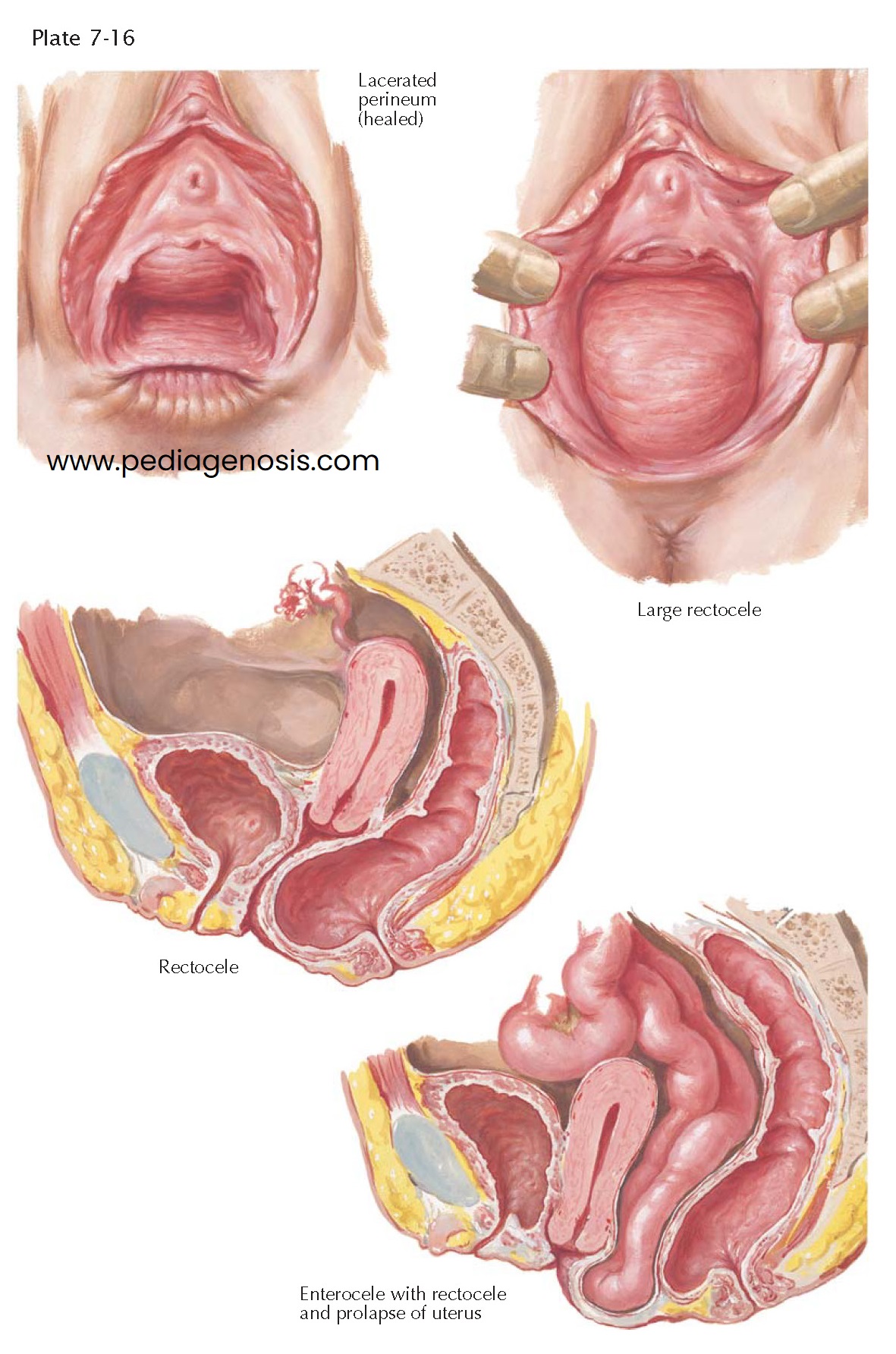

RECTOCELE, ENTEROCELE

Failure of the normal support mechanisms between the rectum and the vagina results in herniation of the posterior vaginal wall and underlying rectum into the vaginal canal and eventually to, and through, the introitus. The clinical end result of posterior obstetric trauma may be a rectocele or enterocele. They can ensue after multiple pregnancies in the absence of severe trauma or, as in cystocele, from any situation that tends to increase the intraabdominal pressure over a long period of time. Congenital weakness, poor health, and poor care predispose to the development of rectocele. Some authors include smoking as a risk factor. A rectocele may be found in 10% to 15% or women, rising to 30% to 40% of women after menopause.

Rectocele seldom occurs alone. When it does, it is usually asymptomatic,

although the patient may complain of a dragging sensation and difficulty evacuating

the rectum when it is full because of the obstruction offered by the bulging

ampulla. However, constipation is more often a contributing cause than an

effect. Rectoceles can be graded by their size, third degree denoting a hernia

to or beyond the introitus. Hemorrhoids, prolapse of the rectal mucosa, and

local infections about the anus may occur in association with large rectoceles.

A rectocele does not cause fecal incontinence if the anal sphincters are

intact.

Surgical repair is indicated when the hernia causes severe symptoms or is

of very large size. It is usually done for first- or second-degree rectocele in

the course of a vaginal plastic operation devised primarily for cystocele and

uterine prolapse, because good levator approximation further buttresses the

anterior wall. If done from below, the operation should include complete

dissection and inversion of the hernial sac (enterocele), plication of the

perirectal fascia, and realignment of the pubococcygeus muscles. In difficult

cases, it is occasionally necessary to make an abdominal approach and suspend

the rectum by suturing it to the posterior vaginal wall and uterosacral

ligaments. The use of natural materials (such as fasciae) or synthetic mesh to

augment surgical repairs has become common, though documentation of their

superiority has not yet been available.

Congenital elongation of the cul-de-sac of Douglas with prolapse of the

intestine or omentum can produce inversion of the pelvic floor in the absence of

obstetric trauma in the condition known as primary enterocele. Since both

rectocele and enterocele present in the posterior vagina, the two conditions

may be difficult to differentiate when they occur together. A horizontal

retraction line in the vaginal epithelium between the hernias may lead to the

correct diagnosis, or reduction of the rectocele may demonstrate another bulge

higher in the vagina. Palpation of

intraperitoneal structures and the presence of peristaltic activity in the sac

are more conclusive evidence. Transvaginal ultrasonography may be used to

assess the presence of an enterocele if not clinically apparent. To overlook

and therefore fail to repair an enterocele is a common cause of recurrence of

prolapse following surgery. Such recurrences are referred to as secondary

enteroceles, but in those cases that have had previous inadequate surgical

treatment of a primary enterocele, the term is a misnomer.

As in the other vaginal hernias, the presence of a mass, pelvic pressure, and sometimes pain cause the enterocele sufferer to seek relief. Intestinal symptoms are rare, and obstruction seldom occurs because of the width of the neck of the sac. High ligation and excision of the peritoneal sac with closure of the uterosacral ligaments by the vaginal approach is the treatment of choice, but an abdominal operation with complete obliteration of the posterior cul-de-sac is sometimes indicated after an unsuccessful vaginal operation.