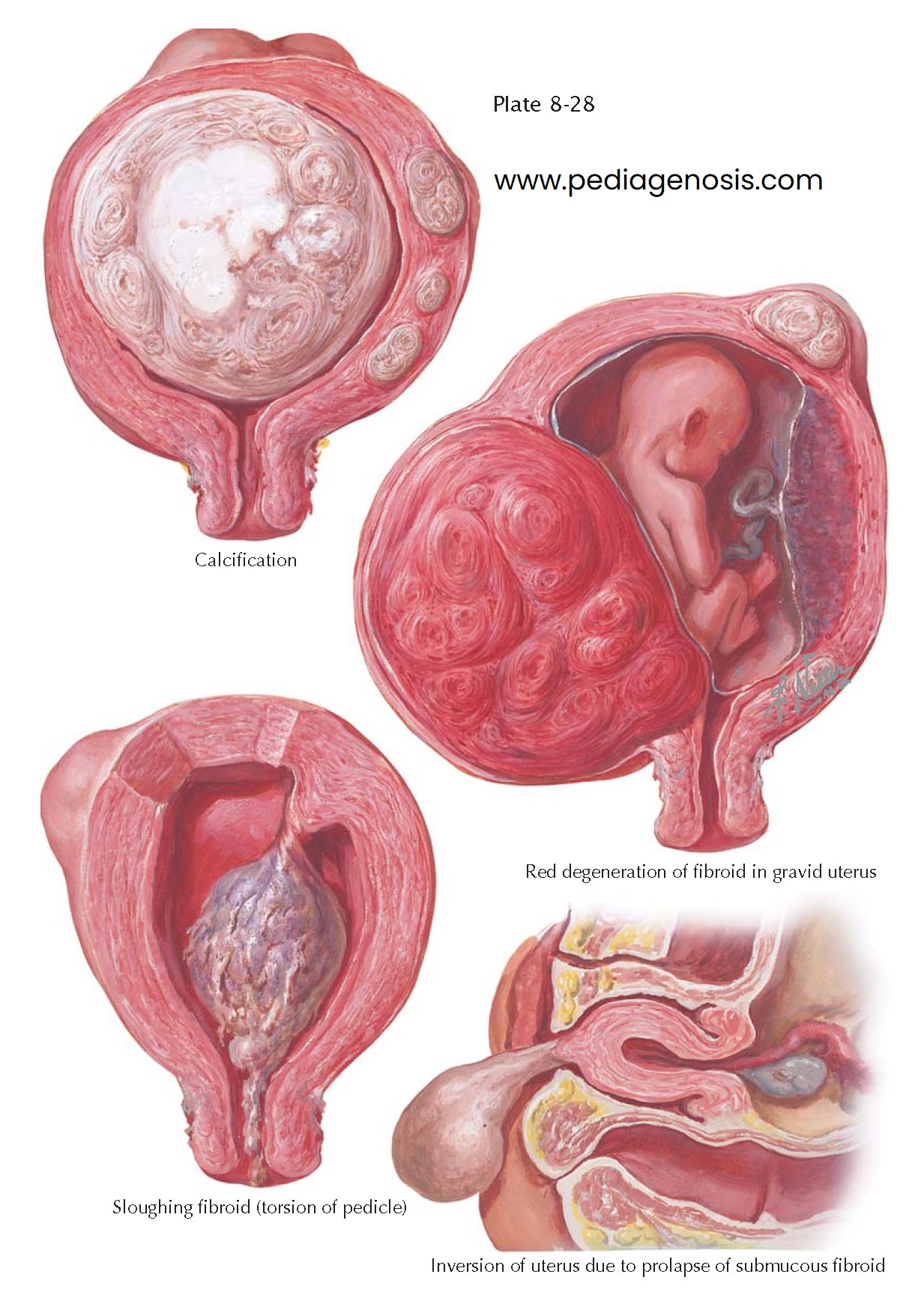

MYOMA (FIBROID) II—SECONDARY CHANGES

Fibroids vary greatly in size and position. Proper management, therefore, demands a consideration of the biologic life cycle of such tumors and an individual evaluation of each patient’s age, physiologic status, and procreative ambitions.

The diagnosis of a fibroid uterus is not in itself a justification for either myomectomy or hysterectomy. Historically, the indications for surgery were undue bleeding, increasing pressure on bladder or bowel, a rapid increase in size or change in consistency of the tumor, or some degenerative change causing pain. With improved imaging and more effective medical therapies available, the need for surgical intervention has been more limited: symptoms unresponsive to therapy and acute pain. There has also been a limited role for myomectomy when a few large fibroids are present and there has been recurrent pregnancy loss.

When a leiomyoma is diagnosed in the absence of any of the indications

just listed, a policy of watchful waiting is justified. If none of these signs

or symptoms is present in younger women with fibroids, the problem may be

complicated by the question of infertility. Small subserous or interstitial

fibroids are unlikely to be etiologically responsible for subfecundity unless

one or both uterine cornua are grossly distorted thereby. On the other hand,

submucous fibroids are more likely to become a factor, because they are commonly

considered to be the cause of prolonged or profuse menses and also may

interfere with implantation. Without a suspicious history of recurrent early

loss, ascribing a role in the infertility to these myoma may be difficult.

Intraligamentary tumors, although rare, may be considered for removal because

if they are left to grow to large size, surgery in this area may become quite

complicated. Pedunculated submucous fibroids may undergo torsion of the pedicle,

cutting off the blood supply and causing slough and necrosis. Occasionally, a

myoma on a long pedicle is gradually forced through the external os and may

prolapse to such a degree as to cause complete

inversion of the uterus.

Large tumors sometimes outstrip their blood supply, and cystic

degeneration may occur centrally. In such cases, the characteristic tough,

rubbery consistency is lost, and the differential diagnosis from sarcomatous

change may have to await removal and gross sectioning. Cystic degeneration is

typified by amorphous, jellylike material in contrast to the friable, red, solid

appearance of a sarcoma.

Occasionally, a fibroid growing downward from the posterior aspect of the

fundus becomes incarcerated in the cavity of the sacrum. It is surprising that

even under these circumstances, lower-bowel or ureteral obstruction is rare,

whereas gross anatomic distortions, such as lateral displacement of the ureters

and rectosigmoid, may occur.

Calcification in a fibroid is not unusual. The deposition of calcium may

throw a characteristic shadow on x-ray

examination, and this is sometimes a valuable aid in the differential diagnosis

of a rocky, hard, pelvic mass in older women.

The relation of fibroids to the successful culmination of pregnancy is affected by the situation in the individual case. The location of the tumor may be more important than its size. Those arising from the cervix or the lower segment may be so large as to cause obstruction of the passage of the fetal head through the birth canal. Although small subserous or interstitial fibroids may not interfere in any way with gestation, during the course of pregnancy (probably owing to pressure), the vascular supply to an interstitial fibromyoma is sometimes sufficiently embarrassed so that hemorrhage into the stroma of the tumor results. This “red degeneration” of the tumor may lead to necrosis and become a serious complication of the pregnancy.