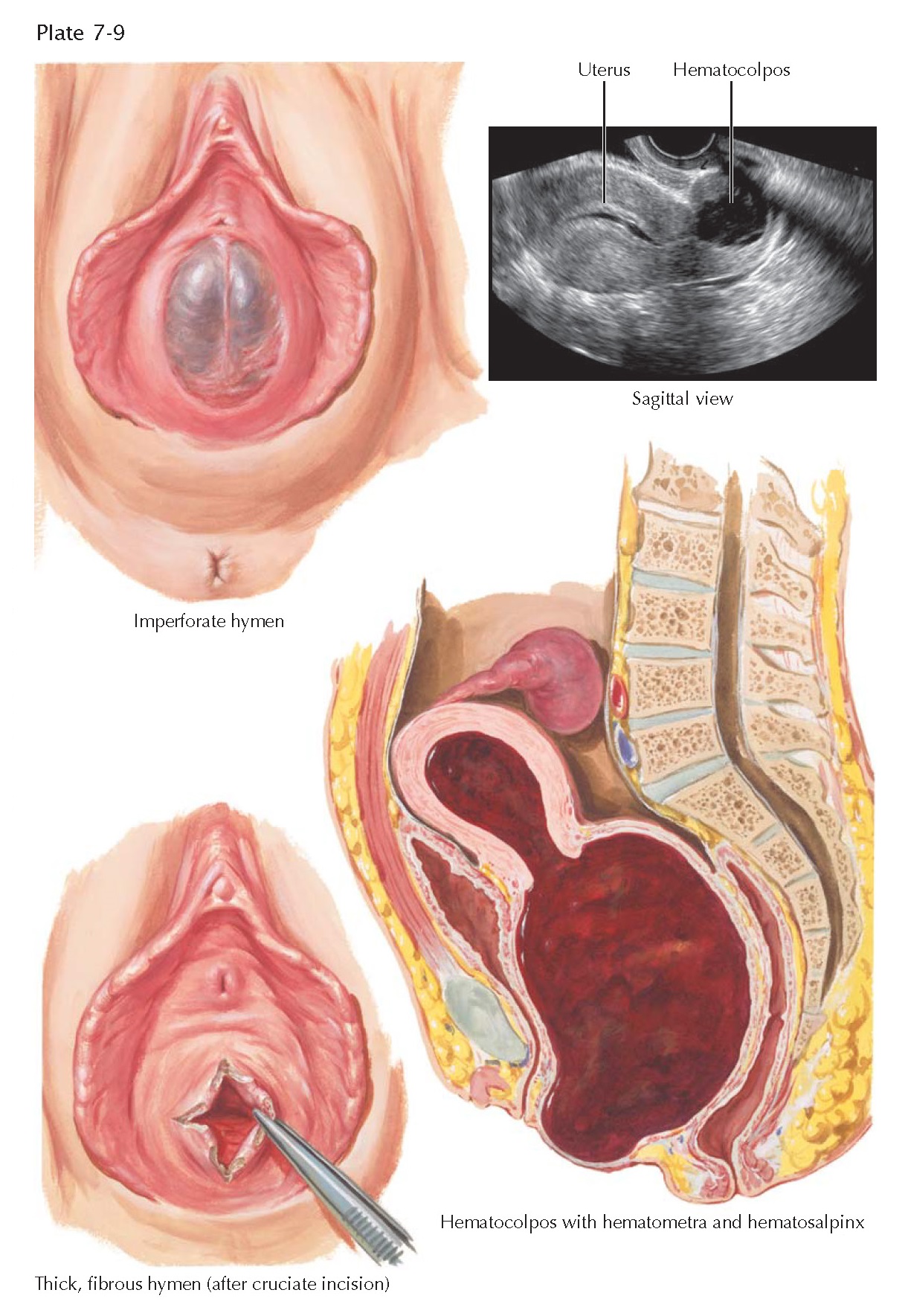

IMPERFORATE HYMEN, HEMATOCOLPOS, FIBROUS

HYMEN

An imperforate hymen is the most commonly encountered anomaly resulting from abnormalities in the development or canalization of the müllerian ducts. It is caused by failure of the endoderm of the urogenital sinus and the epithelium of the vaginal vestibule to fuse and perforate during embryonic development. In addition to primary amenorrhea and coital dysfunction, an imperforate hymen may also be associated with endometriosis, vaginal adenosis, infertility, chronic pelvic pain, long-term sexual dysfunction, and hematocolpos. The hymen, located at the junction of the vagina and the vestibule, is the product of the combined embryo- logic fusion of the urogenital sinus and the müllerian ducts. As the urogenital sinus advances upward like a diverticulum from the outside, it envelops the column of müllerian cells, which has already moved nearly four-fifths of the distance from the cervix down to the vestibule. The infoldings of the sinus at the point of union form the lateral walls of the hymen, but the posterior or dorsal portion is a composite of sinus cells externally and müllerian cells internally. The superficial epithelium of the hymen, as of the vagina and cervical portio vaginalis, is derived entirely from the epithelium of the urogenital sinus, which pushes up the vaginal tube and undergoes differentiation into the stratified squamous layer. The opening of the vagina may occur independently of the formation of the hymen.

It is obvious that the complexity of this embryologic development may

lead to congenital hymenal malformations. The imperforate hymen is usually

detected at birth or puberty. At birth, a hydromucocolpos may accumulate under

the influence of maternal hormones. Hence, at birth a bulging of the imperforate

hymen may be noted between the labia, especially when there is an increase in

intraabdominal pressure such as seen during crying. If there is a significant

hydromucocolpos detected by rectal examination in the newborn, then the hymen

should be excised (cruciate incision followed by excision of margins) to allow

continued drainage. During childhood, the imperforate hymen may be asymptomatic

prior to puberty and may go unrecognized unless detected by careful physical

examination. However, with the beginning of menstruation and the entrapment of

menstrual flow, the vagina gradually becomes distended with blood. From the

pressure of retained blood within the vagina, the hymen bulges outward. As seen

in the cross section, this situation may progress to the extreme, with the

entire vagina engorged with old blood (hematocolpos), the uterus likewise

enlarged by its own retained menstrual flow (hematometra), and blood passing

through the tubal isthmus to form a large hematosalpinx, which occasionally

drains into the peritoneal cavity. Because of the possible impact on the upper

genital tract, ultrasonography to evaluate the

upper genital tract is often indicated. These patients may seek medical

assistance because of primary amenorrhea, pelvic pain (especially cyclic), a

pelvic mass, or occasionally urinary retention with large masses. Incision with

excision of the margins of the hymen and release of the retained blood quickly

relieves the situation. Occasionally, the atresia involves not only the hymen

but also the lowermost portion of the vagina and, in these patients, a somewhat

deeper dissection must be done before the hematoma can be evacuated.

A different form of external vaginal atresia is a thick, fibrous, but not

imperforate hymen, which can easily be incised to produce normal patency of the

vaginal canal. This type of hymen, although much discussed by lay-persons and feared by the unmarried girl, is

relatively uncommon. When it occurs, it may cause dyspareunia. Although

properly considered an anomaly, this malformation, unlike those of the upper

vagina, is usually not associated with congenital anomalies elsewhere in the genitourinary

tract.