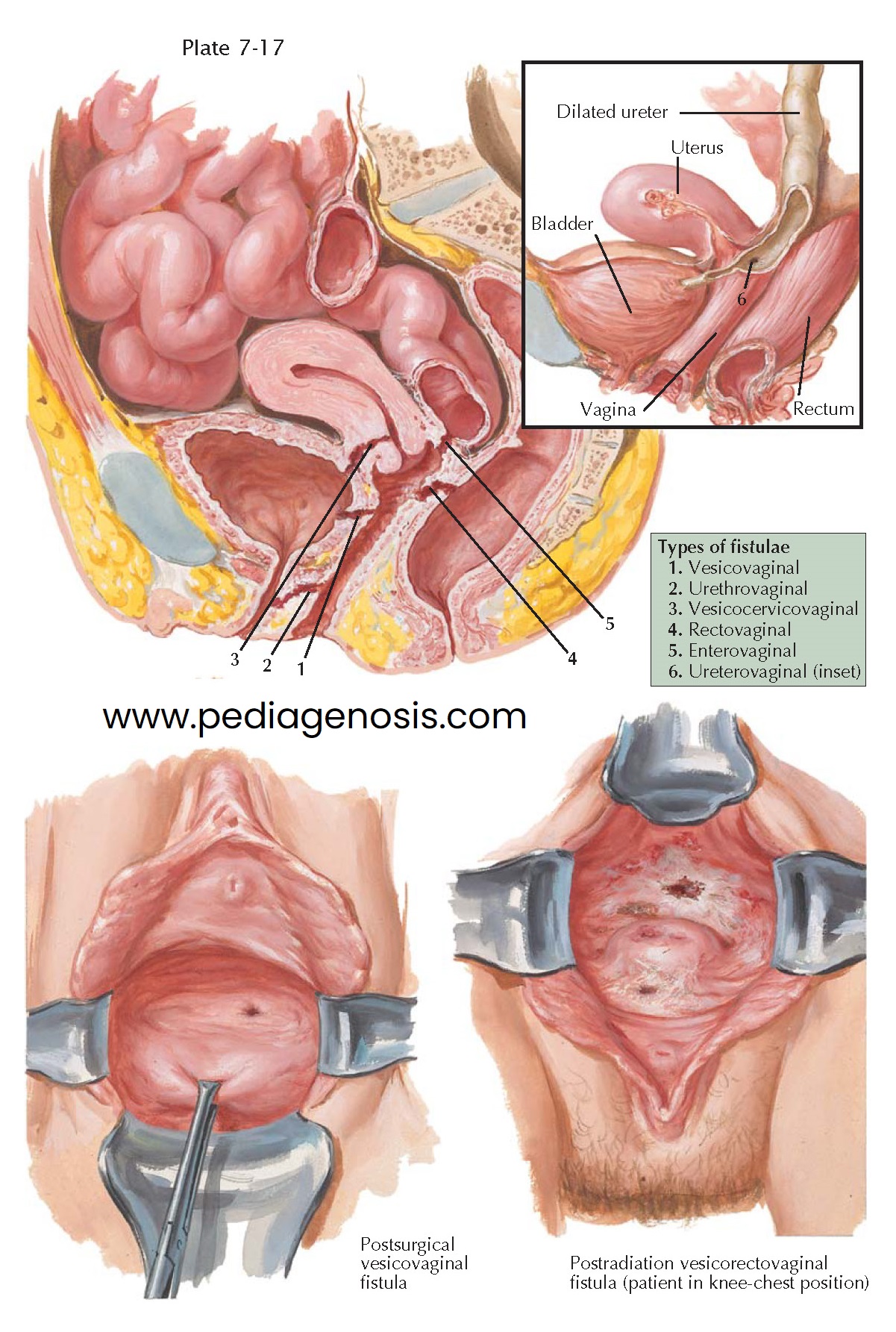

FISTULAE

A fistula is an abnormal communication between two cavities or organs. In gynecology, this usually refers to a communication between the gastrointestinal or urinary tracts and genital tract. Because of its anatomic location in close apposition to the bladder and rectum, the vagina is occasionally the site of fistulae, which divert the urinary and fecal streams, causing incontinence. These fistulae may occur in any part of the vaginal canal and are sometimes multiple.

Urinary tract fistulae may result from surgical or obstetric trauma,

irradiation, or malignancy, although the most common cause by far is unrecognized

surgical trauma. Roughly 75% of urinary tract fistulae occur after abdominal

hysterectomy. Urinary tract fistulae are most common after uncomplicated

hysterectomy, although pelvic adhesive disease, endometriosis, or pelvic tumors

increase the individual risk. Signs of a urinary fistula (watery discharge)

usually occur from 5 to 30 days after surgery (average 8 to 12), although they

may be present in the immediate postoperative period. If the defect is small,

it may spontaneously heal with simple catheter drainage (20% to 30% of

patients). More severe defects should not be repaired until the tissues have

returned to normal condition. Final repair may be by the transvaginal,

transvesical, or transperitoneal routes, depending on the size and position of

the opening. Cystoscopy may be required to evaluate the location of a urinary

tract fistula in relation to the ureteral opening and bladder trigone and to

exclude the possibility of multiple fistulae.

The majority of urethrovaginal fistulae are due to obstetric injury.

However, they may be congenital, the most common form being hypospadia. Unlike

vesicovaginal fistulae, which almost invariably cause urinary incontinence,

urethrovaginal fistulae may be associated with no symptoms, especially if the

defect is located well forward of the vesical neck.

Vesicocervicovaginal fistulae are relatively uncommon and are usually

caused by cancer of the cervix or surgical injury to the bladder in the course

of a subtotal hysterectomy. A fistulous tract in this area is often difficult to

identify and to close.

Fistulae between the gastrointestinal tract and vagina may be

precipitated by the same injuries that cause genitourinary fistulae; most common

are obstetric injuries and complications of episiotomies (lower one-third of

vagina). Fistulae may also follow hysterectomy or enterocele repair (upper

one-third of vagina). Inflammatory bowel disease or pelvic radiation therapy may

hasten or precipitate fistula formation. Although Crohn disease, lymphogranuloma

venereum, or tuberculosis are recognized risk factors, these are uncommon. For

those that do not heal spontaneously (75% of fistulae), the only effective

treatment is surgical. Repair of these fistulae may necessitate diversion of the

fecal stream by colostomy prior to definitive closure. The scarring and

puckering of surrounding tissues produced by radiation therapy greatly reduces

the chances of successful closure. Such lesions must always be biopsied to rule out the possibility of residual malignancy. Surgical treatment of these

defects is complicated, because the underlying pathologic process is usually

still progressing and the results are poor.

Surgical mismanagement accounts for most ureterovaginal fistulae. In the

course of hysterectomy, the ureter may be compressed by clamp or suture just

before it enters the bladder wall, resulting in obstruction, necrosis, and

formation of a new urinary outlet through the upper

vagina. Urinary incontinence of this type can be differentiated from that due

to vesicovaginal fistula by observing the vagina after the introduction of a dye

into the bladder. Ureterovaginal fistulae are of serious significance because

measures to restore the continuity of the urinary tract may be unsuccessful

with loss of the involved kidney.

Occasionally, a combined vesicorectovaginal fistula converts the vagina into a cloaca.