VITAMIN K DEFICIENCY AND VITAMIN K ANTAGONISTS

|

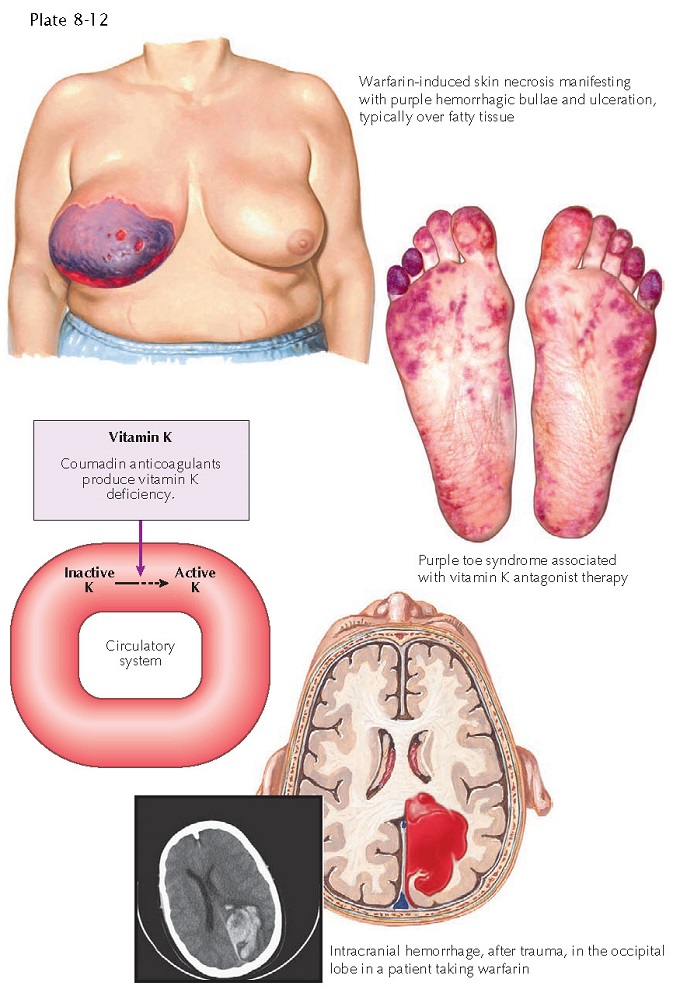

| POTENTIAL CLINICAL CONSEQUENCES OF WARFARIN USE |

Vitamin K is an essential nutrient that is required as a cofactor for the production of a handful of coagulation cascade proteins. It is a fat-soluble vitamin that is efficiently stored in the human body. Vitamin K deficiency is rare and is typically seen only transiently in neonates and infants during the first 6 months of life. Affected neonates may show abnormally prolonged bleeding after minor trauma. Patients may have an elevated pro- thrombin time (PT) and decreased serum levels of vitamin K and coagulation factors. Therapy consists of replacement of vitamin K to normal levels and a search for any possible underlying cause, such as liver or gastrointestinal disease. Neonatal and infantile vitamin K deficiency is most likely caused by maternal breast milk insufficiency of vitamin K.

Vitamin K

deficiency is rarely seen in adults, because most diets contain enough vitamin

K for normal physiological functioning. Adult patients with liver disease and

malabsorption states are at highest risk for the development of vitamin K

deficiency. Vitamin K may be found in two natural forms: vitamin K1

(phylloquinone) and vitamin K2 (menaquinone). K1 is found in plants, and K2 is

produced by various bacteria that make up the normal flora of the

gastrointestinal tract. Anti- biotics may cause a decrease in the bacterial

production of vitamin K2, resulting in a lack of vitamin K available for

absorption. This is typically not a clinical issue unless the patient is taking

a vitamin K antagonist such as warfarin. Vitamin K is absorbed in the distal

jejunum and ileum via passive diffusion across the cell membrane. The

majority of vitamin K is stored normally in the liver. There, the vitamin is

converted to its active state, hydroxyquinone. An efficient vitamin K salvage

pathway normally prevents an individual from becoming deficient in the vitamin.

The enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase is responsible for converting the

inactive epoxiquinone to the active hydroxyquinone form of vitamin K.

Warfarin is

a synthetic analogue of vitamin K and is the main vitamin K antagonist. It is indicated for use as an

anticoagulant in the treatment of a number of conditions, including atrial

fibrillation and deep venous thrombosis, and after heart valve replacement

surgery. Warfarin acts by inhibiting the enzymes that are responsible for

carboxylation of glutamate residues and epoxide reductase. This both decreases

the available clotting factors and induces vitamin K deficiency, leading to

added reduction of available clotting factors. Clinical Findings: Vitamin

K antagonists have been shown to cause a specific type of cutaneous eruption

known as warfarin necrosis, which occurs in approximately 0.05% of patients

taking the medication. Warfarin necrosis affects the areas of the body that

have increased body fat, such as the breasts, the abdominal pannus, and the

thighs. The feet are also particularly prone to development of warfarin

necrosis. The skin initially

develops small, red to violaceous petechiae and macules preceded by

paresthesias. These regions become erythematous and purple (ecchymoses) with

intense edematous skin. The lesions eventually ulcerate or form hemorrhagic

bullae. The hemorrhagic bullae desquamate, leaving deep ulcers. Painful

cutaneous ulcers may occur, with some extending into the subcutaneous tissue,

including muscle. Most ulcers appear within 5 to 7 days after the initiation of warfarin therapy. Secondary

infection may be a cause of significant morbidity. The affected areas continue

to undergo necrosis unless the warfarin is withheld and the patient is treated

with a different class of anticoagulant. The feet and lower extremities may

have a reticulated, purplish dis- coloration called “purple toe syndrome.” This

cutaneous drug reaction can be eliminated or at least drastically decreased if the patient

is pretreated with heparin or another equivalent anticoagulant before warfarin

is initiated.

Histology:

Skin

biopsies from areas of warfarin necrosis show an ulcer with a mixed

inflammatory infiltrate. Thrombosis is seen within the small vessels (venules

and capillaries) of the cutaneous vasculature. Arterial involvement is absent.

Minimal to no inflammatory infiltrate is present. Red blood cell extravasation

is prominent. The main histopathological finding is microthrombi. Findings of

inflammation, a neutrophilic infiltrate, arterial involvement, a strong

lymphocytic infiltrate, or the presence of bacteria in or around vessels

mitigate against the diagnosis of warfarin necrosis. Bacteria will be present

on the surface of the ulcer and are believed to be a secondary phenomenon.

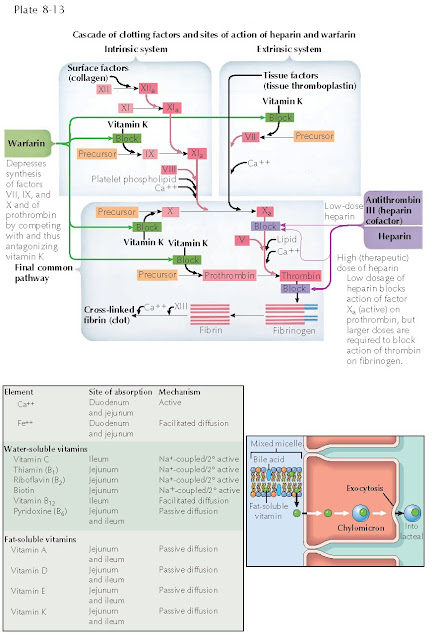

Pathogenesis:

Vitamin

K is needed for the modification of many coagulation cascade proteins,

including protein C, protein S, factor II (prothrombin), factor VII, factor IX,

and factor X. Factors II, VII, IX, and X are critical in forming a clot and are

produced in the liver as inactive precursors. Preactivation of these clotting

factors requires the action of vitamin K carboxylation on glutamate amino acid

residues. Once preactivated, the clotting factors are available for full

activation and clot formation when exposed to calcium and phospholipids on the

surface of platelets.

|

| ANTICOAGULATION EFFECTS ON THE CLOTTING CASCADE |

Inhibition

of these clotting factors by vitamin K antagonists leads to anticoagulation.

Warfarin works by inhibiting the carboxylation of glutamate. On the other hand,

protein C and protein S are responsible for turning off the clotting cascade

and play a natural regulatory role in normal coagulation. When these proteins

are inhibited, the clotting cascade may proceed unimpeded, allowing for

excessive clotting. Protein C and protein S have shorter half-lives than

factors II, VII, IX, and X. Therefore, when individuals are treated initially

with warfarin, the levels of protein C and protein S are depleted before the

other factors, leading to a prothrombic state.

This initial prothrombic state is responsible for the clinical signs and

symptoms of microvasculature blood clotting and skin necrosis. The clotting

takes place in areas of increased adipose tissue because of the sluggish flow

of blood through the fine vasculature in these regions. For this reason, most

patients are given heparin or a similar anticoagulant until the full effect of

warfarin on all clotting factors has occurred.

Therapy:

Treatment

of warfarin necrosis requires discontinuation of warfarin and initiation of

heparin anticoagulation and supportive care with fresh-frozen plasma and

vitamin K replace the lost protein C and protein S. Surgical debridement may be

required, and one should be vigilant for any signs or symptoms of secondary

infection. Therapy consists of proper replacement of vitamin K and supportive care. Menadione is a synthetic

form vitamin K that can be given therapeutically.

Vitamin K deficiency in neonates and infants is diagnosed by an isolated elevation in the prothrombin time. The levels of the vitamin K–dependent clotting cofactors can each be measured, and vitamin K replacement should be administered to those who are deficient. Breast milk is not a strong source of vitamin K, and if the mother had previous children with vitamin K deficiency, the newborn should be given supplemental vitamin K. The best method for supplementation has yet to be determined, but it can be achieved with a one-time intramuscular injection or with oral replacement.