Valves

|

| CARDIAC VALVES OPEN AND CLOSED |

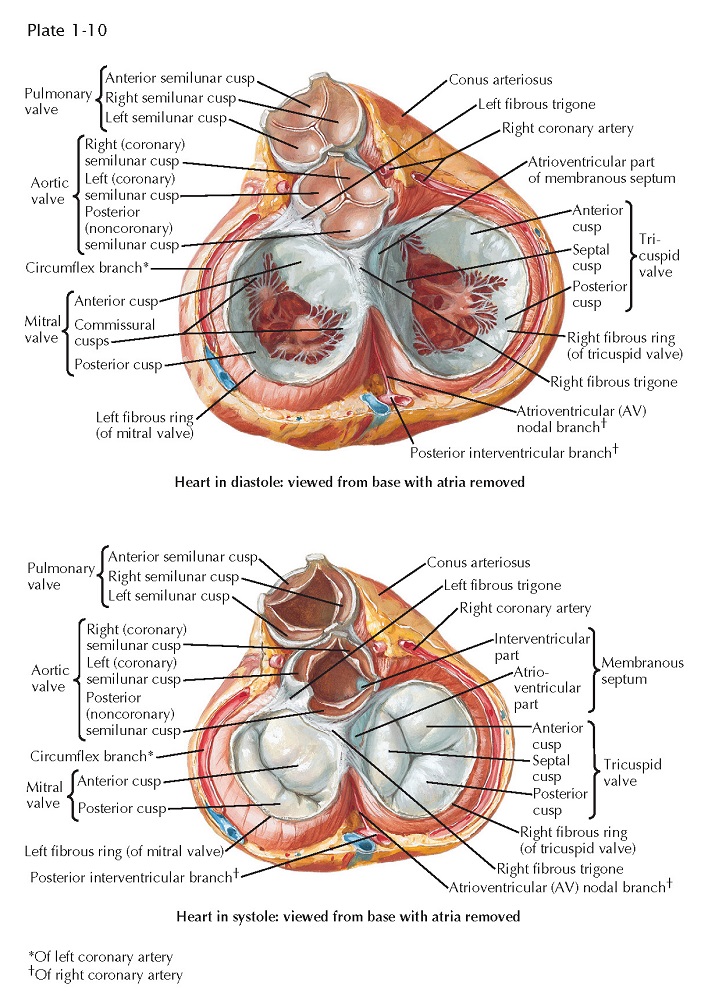

Each atrioventricular (AV) valve apparatus consists of a number of cusps, chordae tendineae, and papillary muscles. The cusps are thin, yellowish white, glistening trapezoid-shaped membranes with fine, irregular edges. They originate from the annulus fibrosus, a poorly defined and unimpressive fibrous ring around each AV orifice. The amount of fibrous tissue increases only at the right and left fibrous trigones.

The atrial surface of the AV valve

is rather smooth (except near the free edge) and not well demarcated from the

atrial wall. The ventricular surface is irregular because of the insertion of

the chordae tendineae and is separated from the ventricular wall by a narrow

space. The extreme edges of the cusps are thin and delicate with a sawtooth

appearance from the insertion of equally fine chordae. Away from the edge, the

atrial surface of the cusps is finely nodular, particularly in small children.

These nodules are called the noduli Albini. On closure of an AV valve, the

narrow border between the row of Albini nodules and the free edge of each cusp

presses against that of the next, resulting in a secure, watertight closure.

The chordae tendineae may be divided into the

following three groups:

The chordae of the first order

insert into the extreme edge of the valve by a large number of very fine

strands. Their function seems to be merely to prevent the opposing borders of

the cusps from inverting.

The chordae of the second order

insert on the ventricular surface of the cusps, approximately at the level of

the Albini nodules, or even higher. These are stronger and less numerous. They

function as the mainstays of the valves and are comparable

to the stays of an umbrella.

The chordae of the third order

originate from the ventricular wall much nearer the origin of the cusps. These

chordae often form bands or foldlike structures that may contain muscle.

The first two groups originate from

or near the apices of the papillary muscles. They form a few strong, tendinous

cords that subdivide into several thinner strands as

they approach the valve edges. Occasionally, particularly on the left side, the

chordae of the first two orders may be wholly muscular, even in normal hearts,

so that the papillary muscle seems to insert directly into the cusp. This is

not surprising because the papillary muscles, the chordae tendineae,

and most of the cusps are derived from the embryonic ventricular

trabeculae and therefore were all muscular at one time.

The tricuspid valve consists

of an anterior, a medial (septal), and one or two posterior cusps.

The depth of the commissures between the cusps is variable, but the

commissures never reach the annulus, so the cusps are only incompletely

separated from each other.

|

| VALVES AND FIBROUS SKELETON OF HEART |

The mitral (bicuspid) valve

actually is made up of four cusps: two large ones—the anterior (aortic)

and posterior (mural) cusps—and two small commissural cusps.

Here, as in the tricuspid valve, the commissures are never complete, and they

should not be so constructed in the surgical treatment of mitral stenosis.

The arterial or semilunar valves

differ greatly in structure from the AV valves. Each consists of three

pocketlike cusps of approximately equal size. Although, functionally the

transition between the ventricle and the artery is abrupt and easily

determined, this cannot be done anatomically in any simple manner. There is no

distinct, circular ring of fibrous tissue at the base of the arteries from which these and the valve

cusps arise; rather, the arterial wall expands into three dilated pouches, the

sinuses of Valsalva, whose walls are much thinner than those of the aorta or

pulmonary artery. The origin of the valve cusps is therefore not straight but

scalloped.

The cusps of the arterial semilunar

valve are largely smooth and thin. At the center of the free margin of each

cusp is a small fibrous nodule called the nodulus

Arantii. On each side of the nodules of Arantius, along

the entire free edge of the cusp, there is a thin, half-moon–shaped area

called the lunula that has fine striations parallel to the edge. The

lunulae are usually perforated near the insertion of the cusps on the aortic

wall. In valve closure, because the areas of adjacent lunulae appose each

other, such perforations do not cause insufficiency of the valve and are

functionally of no significance.