Overview of Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage

|

| CAUSES OF GASTROINTESTINAL HEMORRHAGE |

Many gastrointestinal disorders manifest themselves by bleeding. Intestinal bleeding may present as bright-red blood, suggesting gross lower bleeding (hematochezia), passage of black stool (melena), or other findings of bleeding but no change in stool color (occult bleeding). When no cause of bleeding can be detected with the usual examinations, obscure gastrointestinal bleeding is occurring.

More

severe hemorrhages reveal themselves by the appearance of visible blood in the

stool, where it may be intermingled with the fecal material as bright-red blood

(hematochezia) or appear as bloody diarrhea. Hematochezia in small

volumes is almost always caused by a colonic lesion. In contrast, passage of

large volumes of red blood or bloody stools may be caused by intestinal

disorders or upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage, in which case it signifies

massive bleeding. It is often noted that the “most common etiology of

hemodynamically significant lower GI bleeding is an upper GI source” originating

above the ligament of Treitz. Lesions causing upper gastrointestinal bleeding

can accurately be detected in more than 95% of cases by upper endos- copy.

Upper endoscopy is a procedure of shorter duration than colonoscopy, does not

require bowel preparation, and often detects lesions that can be easily treated

by a wide variety of effective devices. If upper endoscopy is negative,

attention should be directed to the colon as the most likely source and to the

small intestine only if thorough evaluations of both the upper digestive tract

and colon are negative.

Distinguishing

upper bleeding from lower bleeding is often challenging, even for experts.

Bleeding that is at first thought to originate in the colon will later be

determined to be from an upper source in 15% of patients. An upper digestive

organ source is confirmed in patients with hematemesis,

blood in a nasogastric lavage, or blood seen endoscopically. An upper source

should be pursued before proceeding with colonoscopy whenever bleeding is brisk

and hemodynamically significant, there is melena, there is known or suspected

liver disease, the patient has been taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory

drugs, or there are known upper pathologic findings. Lower gastrointestinal

bleeding is less likely if the blood urea nitrogen–to-creatinine ratio is

higher than 25 and very unlikely if the ratio is higher than 50.

Substantial

bleeding may also present as black stool, known as melena. The black

color indicates that blood has been exposed to the digestive activity of

intestinal secretions, and therefore, as a rule, it is a sign that the bleeding

originates from a lesion in the gut above the cecum. Rarely, however, melena

may occur with lesions located as low as the left colon. Because colonoscopy will

detect a source of bleeding in the colon in less than 5% of patients with

melena who have had a negative endoscopic examination, it is imperative that a

thorough upper examination be performed first in all patients with melena as

well as in those with overt bleeding.

The

loss of blood from the intestines may be so minimal that, in the absence of

other symptoms, it may escape attention until microcytic anemia is seen as the

first sign of a gastrointestinal disorder. Because bleeding is often the only

sign of serious pathologic situations in the digestive tract, it is important

to include an evaluation for fecal “occult” blood at the slightest suspicion of

a lesion in the gut.

|

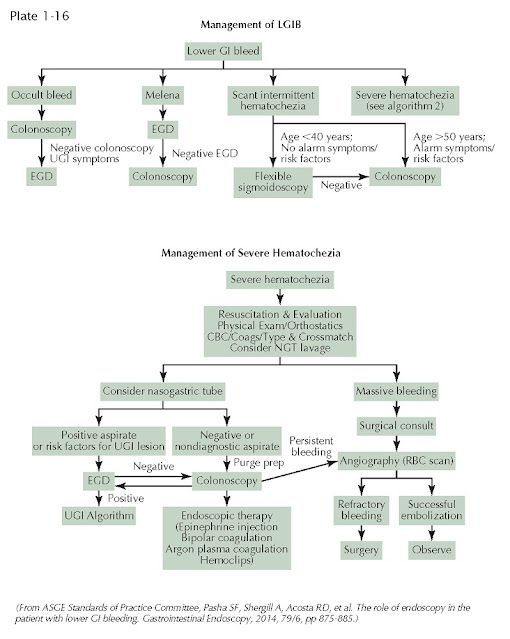

| MANAGEMENT OF GASTROINTESTINAL HEMORRHAGE |

To

avoid pitfalls, one should remember that neither stool color nor the presence

of blood on fecal occult blood testing is conclusive evidence that a lesion is

present in the digestive system. The stool may be discolored for reasons other

than the presence of blood. The stool is often gray or black in patients taking

iron or bismuth preparations. It may be reddish when the patient has eaten

beets or other red substances if transit is rapid, as occurs with severe

diarrhea. Likewise it is important to appreciate that bleeding originating in

the oral or pharyngeal cavity or from hemorrhagic lesions in

the respiratory tract can be detected in the feces. Vaginal bleeding may

also be mistaken as rectal bleeding. More commonly, false-positive testing for

occult blood occurs in patients eating red meat. Such false-positive results

can be avoided if testing is performed with immune techniques that accurately

detect only human hemoglobin.

Before

proceeding with definitive testing and possible treatment with endoscopic

techniques, the airway, breathing, and circulatory status of the patient must

be promptly assessed and secured (ABCs of emergency care). The history should

focus on potential causes, the volume of blood lost, the presence of any signs

or symptoms of coagulopathy (including use of nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory drugs), and the presence of comorbidities. Correcting any of

these existing problems must be the foremost priority during the first 24 hours

after the patient is admitted to the hospital. Laboratory testing, including a

complete metabolic panel, complete blood count, and coagulation studies, should

be sent for stat analysis. Blood should be drawn for blood typing and, when

appropriate, for cross-matching. Only when the patient is hemodynamically

stable and any ongoing concurrent illnesses have been addressed and optimized

should the bowel be thoroughly prepped for an urgent colonoscopic examination.

The

source of lower gastrointestinal bleeding can be accurately detected in most

patients by colonoscopy. In a select

clinical setting, particularly when the patient has recently had a normal

colonoscopy and describes low-volume hematochezia, a sigmoidoscopy may be all

that is needed. It is particularly useful to perform sigmoidoscopy when the

patient is actively experiencing bleeding. Hemorrhoids missed by flexible

endoscopic techniques may be more accurately detected with rigid proctoscopy.

When upper endoscopy and colonoscopy fail to identify a source,

balloon-assisted enteroscopy can reach most, if not all, of the jejunum and

ileum. Sources of bleeding can often be treated using these endoscopic

techniques. The use of other techniques to detect bleeding sources, including

capsule enteroscopy, nuclear scans, angiography, and cross-sectional imaging techniques,

is described in Plates 2-12 and 2-33.