CUSHING’S SYNDROME: PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

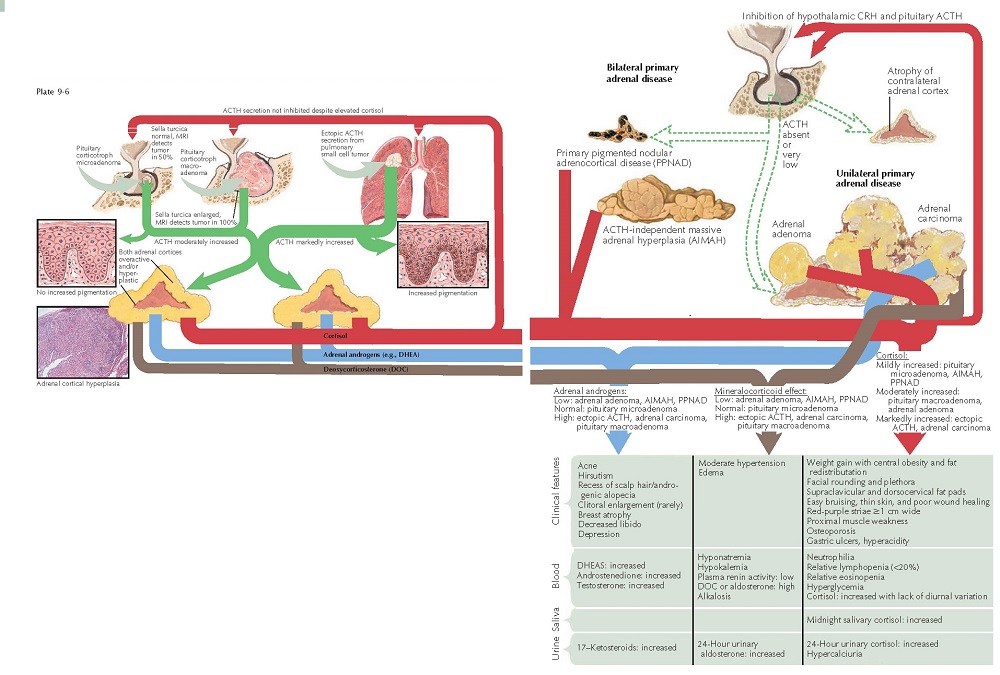

Cushing’s syndrome is directly caused by excessive amounts of glucocorticoids and their effects on numerous organ systems. Cortisol is strikingly elevated in all cases of Cushing’s syndrome. In some cases, levels of 17-ketosteroids and aldosterone are slightly elevated, and this plays a role in the clinical manifestations of the disease. There are numerous disease states that can cause hypercortisolemia, including excessive secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH, corticotropin), adenoma and hyperplasia of the adrenal gland, carcinoma of the adrenal gland, primary pigmented nodular adrenocortical disease (PPNAD), and exogenous cortisol use. In all cases, it is the marked elevation of cortisol that ultimately is the cause of the disease.

Normally,

ACTH is produced and regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)

axis. Corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is the main hypothalamic regulator

of pituitary ACTH production. CRH acts on the corticotroph cells of the

anterior pituitary, causing them to secrete pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), which

is posttranslationally modified into ACTH. ACTH then acts on the adrenal glands

to increase production of cortisol. Normally, cortisol and ACTH both act in a

negative feedback loop to inhibit excessive secretion of CRH.

Excessive

ACTH may be produced in several ways. Most often, it is produced from a

basophilic adenoma of the anterior stalk of the pituitary gland. The term

Cushing’s

disease should

be used in cases of anterior pituitary ACTH-secreting tumors. All other forms

of the condition should be referred to as Cushing’s syndrome. In

basophilic adenomas of the pituitary, the size of the sella turcica can range

from normal to dramatically enlarged. ACTH production is elevated and is not

suppressed by the increase in the cortisol level. Bilateral adrenal hyperplasia

is seen, because the ACTH acts to increase the production of cortisol by the

adrenal glands. ACTH is produced in the pituitary by posttranslational

modification of the protein POMC. POMC is modified by various enzymes to produce

ACTH, β-lipotropin, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH).

ACTH is further broken down to produce MSH. β-lipotropin is broken down to produce β- endorphin. Cushing’s disease is associated with a

generalized skin hyperpigmentation caused by increased melanin production that

is directly related to the effects of MSH on the cutaneous melanocytes.

Hyperpigmentation of the skin is seen only in patients with an abnormally

elevated ACTH secretion.

Excessive

ACTH may also be produced from ectopic ACTH-producing tumors, most frequently

broncho- genic small cell tumor. Most patients present with signs and symptoms

of Cushing’s syndrome before the underlying tumor is diagnosed. This form of

Cushing’s syndrome can be very difficult to differentiate from Cushing’s

disease in the early stages of each, and the clinician needs to be aware of the

various pathophysiological mechanisms involved in excessive ACTH production.

When faced with a patient with excessive ACTH production, the clinician must

perform a thorough evaluation, including history, physical examination, and

laboratory and radiological testing, to determine the etiology.

Cortisol

excess may also be seen in primary adrenal disease caused by benign bilateral

adrenal hyperplasia, a cortisol-secreting adenoma, or, less likely, a

carcinoma. In these cases, plasma ACTH levels are reduced to near zero, due to

the effect of the negative feedback loop on the HPA axis. The uninvolved

adrenal gland is typically atrophic. Exogenous steroid use can also lead to Cushing’s

syndrome. In those cases, the ACTH level is decreased and the adrenal glands

are atrophic.

Regardless

of the etiology of Cushing’s disease or Cushing’s syndrome, the clinical

manifestations are caused almost entirely by excessive cortisol production in

the zona fasciculata of the adrenal gland. Cortisol is a catabolic steroid and

causes profound muscle weakness if allowed to persist. Adipose tissue

redistribution is prominent. Central obesity is easily observed, with a

thinning of the extremities. Supraclavicular and posterior cervical (“buffalo

hump”) fat pads are frequently encountered. Cortisol has negative effects on

the connective tissue of the skin, leading to a decrease in collagen. This, in

turn, leads to an increase in capillary fragility, easy bruising, ecchymoses,

and a thin or translucent appearance to the skin. Prominent purple to red

striae are seen as a result of the loss of normal connective tissue function

within the skin. The striae are most prominent in areas of obesity and are made

more noticeable by the central fat redistribution. Facial plethora is

frequently seen and is likely caused by thinning of the skin and an underlying

polycythemia. Excessive cortisol leads to increased blood glucose levels; this

in turn can lead to poor wound healing and an increase in infections.

Hyperglycemia can lead to polyuria and polydipsia.

Most

patients with elevated cortisol levels exhibit some degree of central nervous

system involvement.

Fatigue,

lethargy, emotional disturbance, depression, and occasionally psychosis are

diagnosed in these patients. Excess cortisol can cause an increase in gastric

acidity, leading to severe peptic ulcer disease. Patients with Cushing’s

syndrome are more likely to have severe recalcitrant peptic ulcer disease than

the average peptic ulcer patient.

In some patients, levels of 17-ketosteroids and aldosterone are moderately elevated. This leads to acne, which is often nodulocystic and recalcitrant to therapy. Hirsutism and premature or accelerated androgenetic alopecia may be seen. In rare cases, clitoral enlargement and breast atrophy are seen. A decrease in libido is extremely common. Excessive aldosterone may lead to hypertension, hyponatremia, and a metabolic hypokalemic alkalosis. The elevation of 17-ketosteroids and aldosterone is most frequently associated with adrenal carcinoma.