Atria and Ventricles

The right atrium consists of two parts: (1) a posterior smooth-walled part derived from the embryonic sinus venosus, into which enter the superior and inferior venae cavae, and (2) a thin-walled trabeculated part that constitutes the original embryonic right atrium. The two parts of the atrium are separated by a ridge of muscle. This ridge, the crista terminalis (see Plate 1-7), is most prominent superiorly, next to the SVC orifice, then fades out to the right of the IVC ostium. Its position corresponds to that of the sulcus terminalis externally (see Plate 1-6). Often described as a remnant of the embryonic right venous valve. the crista terminalis actually lies just to the right of the valve.

From the lateral aspect of the

crista terminalis, a large number of pectinate muscles run laterally and

generally parallel to each other along the free wall of the atrium. The atrial

wall is paper-thin and translucent between the pectinate muscles. The

triangular-shaped superior portion of the right atrium—the right auricle—is

also filled with pectinate muscles. One pectinate muscle originating from the

crista terminalis is usually larger than the others and is called the taenia

sagittalis.

The right auricle usually is not

well demarcated externally from the rest of

the atrium. The right auricle is a convenient, ready-made point of entry for

the cardiac surgeon and is used extensively.

The

anterior border of the IVC ostium is guarded by a fold of tissue, the inferior

vena cava (eustachian) valve, which varies greatly in size and may

even be absent. When large, the IVC valve is usually perforated by numerous

openings, forming a delicate lacelike structure known as the network of Chiari.

The coronary sinus enters the right atrium just anterior to the medial

extremity of the IVC valve. The eustachian valve’s orifice may also be

guarded by a valvelike fold, the coronary sinus (thebesian) valve.

Both IVC valves and coronary sinus valves are derived from the large, embryonic

right venous valve.

The posteromedial wall of the right

atrium is formed by the interatrial septum, which has a thin, fibrous,

central ovoid portion. The interatrial septum forms a shallow depression in the

septum called the fossa ovalis. The remainder of the septum is muscular

and usually forms a ridge around the fossa ovalis, the limbus fossae ovalis.

A probe can be passed under the anterosuperior part of the limbus into the

left atrium in some cases, and the foramen (fossa) ovalis is then “probe

patent.” Anteromedially, the tricuspid valve gives access to the right

ventricle.

RIGHT VENTRICLE

The right ventricular cavity (see

Plate 1-7) can be divided arbitrarily into a

posteroinferior inflow portion, containing the tricuspid valve, and an

anterosuperior outflow portion, from which the pulmonary trunk originates.

These two parts are separated by prominent muscular bands, including the parietal

band, the supraventricular crest (crista supraventricularis), the septal

band, and the moderator band. These bands form a wide, almost circular

orific with no impediment to flow in the normal

heart.

The wall of the inflow portion is

heavily trabeculated, particularly in its most apical portion. These trabeculae

carneae enclose a more or less elongated, ovoid opening. The outflow

portion of the right ventricle, often called the infundibulum, contains only a

few trabeculae. The subpulmonic area is smooth walled.

A number of papillary muscles anchor

the tricuspid valve cusps to the right ventricular wall through many

slender, fibrous strands called the chordae tendineae. Two papillary

muscles, the medial and anterior, are reason- ably constant in position

but vary in size and shape. The other papillary muscles are extremely variable

in all respects. Approximately where the crista supraventricularis joins the

septal band, the small medial papillary muscle receives chordae

tendineae from the anterior and septal cusps of the tricuspid valve. Often well

developed in infants, the medial papillary muscle is almost absent in adults or

is reduced to a tendinous patch. An important surgical landmark, the medial

papillary muscle is also of diagnostic value to the cardiac pathologist with

its interesting embryonic origin. The anterior papillary muscle originates

from the moderator band and receives chordae from the anterior and posterior

cusps of the tricuspid valve. In variable numbers, the usually small posterior

papillary muscle and septal papillary muscle receive chordae from the

posterior and medial (septal) cusps. The muscles originating from the

posteroinferior border of the septal band are important in the analysis of some congenital cardiac anomalies.

The pulmonary trunk arises

superiorly from the right ventricle and passes backward and slightly upward. It

bifurcates into right and left pulmonary arteries (see Plate 1-7) just

after leaving the pericardial cavity. A short ligament—the ligamentum

arteriosum (see Plate 1-8)—connects

the upper aspect of the bifurcation to the inferior surface of the aortic

arch (arch of aorta; see Plate 1-6). It is a remnant of the fetal ductus arteriosus (duct of Botallo).

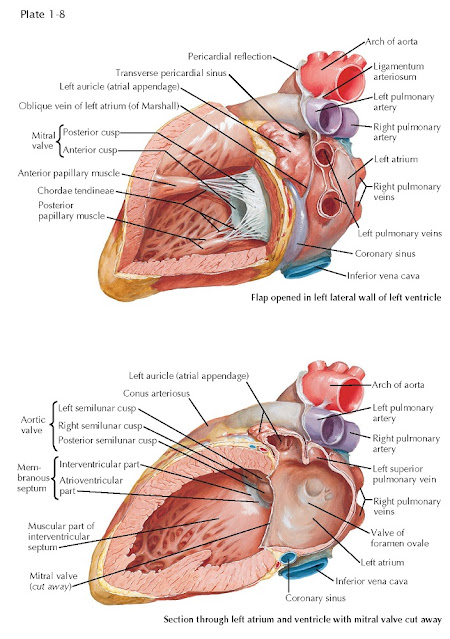

LEFT ATRIUM AND LEFT VENTRICLE

LEFT ATRIUM

The left atrium consists mainly of a

smooth-walled sac with the transverse axis larger than the vertical and

sagittal axes. On the right, two or occasionally three pulmonary veins enter

the left atrium; on the left there are also two (sometimes one) pulmonary

veins. The wall of the left atrium is distinctly thicker than that of the right

atrium. The septal surface is usually fairly smooth, with only an irregular

area indicating the position of the fetal valve

of the foramen ovale. A narrow slit may allow a probe to be passed from the

right atrium to the left atrium.

The left auricle is a continuation

of the left upper anterior part of the left atrium. The auricle’s variable

shape may be long and kinked in one or more places. Its lumen contains small

pectinate muscles, and there usually is a distinct waistlike narrowing proximally.

ATRIA, VENTRICLES, AND INTERVENTRICULAR SEPTUM

The left ventricle (see Plate

1-8) is egg shaped with the blunt end cut off, where the mitral valve and

aortic valve are located adjacent to each other. The valves are separated

only by a fibrous band giving off most

of the anterior (aortic) cusp of the mitral valve and the

adjacent portions of the left and posterior aortic valve cusps. The

average thickness of the left ventricular (LV) wall is about three times that

of the right ventricular (RV) wall. The LV trabeculae carneae are somewhat less

coarse, with some just tendinous cords. As in the right ventricle, the

trabeculae are much more numerous and dense in the apex of the left ventricle. The

basilar third of the septum is smooth.

Usually there are two stout papillary

muscles. The dual embryonic origin of each is often revealed by their bifid

apices; each receives chordae tendineae from both major mitral

valve cusps. Occasionally a third, small papillary muscle is present

laterally.

Most of the ventricular septum is

muscular. Normally it bulges into the right ventricle, showing that a transverse

section of the left ventricle is almost circular. The muscular portion

has approximately the same thickness as the parietal LV wall. The ventricular

septum consists of two layers, a thin layer on the RV side and a thicker layer

on the LV side. The major septal arteries tend to run between these two layers.

In the human heart a variable but generally small area of the septum immediately

below the right and posterior aortic valve cusps is thin and

membranous.

The demarcation between the muscular

and the membranous part of the ventricular septum is distinct and is

called the limbus marginalis. As seen from the opened right ventricle (see Plate 1-7, bottom),

the membranous septum lies deep to the supraventricular crest and

is divided into two parts by the origin of the medial (septal) cusp of

the tricuspid valve. As a result, one portion of the membranous septum

lies between the left ventricle and the right ventricle—the interventricular

part— and the other between the left ventricle and the right atrium—the atrioventricular

part.

On sectioning of the septum in an approximately transverse plane, the basilar portion of the ventricular septum, including the membranous septum, is seen to deviate to the right, so that a plane through the major portion of the septum bisects the aortic valve. It must be emphasized that the total cardiac septum shows a complex, longitudinal twist and does not lie in any single plane.