SARCOIDOSIS

Sarcoidosis is a common disease of unknown origin characterized by the infiltration of many organs by non-caseating epithelioid granulomas. The lung is the most common organ affected by sarcoidosis. The skin, eye, and liver are also frequently involved. Sarcoidosis may affect many other organs, many of which are detailed in the next paragraph. Although in the United States sarcoidosis is most common in African Americans, the disease is also has a high prevalence in Northern Europeans and occurs worldwide. Women appear to contract the disease more often than men. The majority of patients are younger than 40 years of age at onset, although there is a second peak of increased incidence after age 50 years in women. There is a higher incidence of the disease in first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and children) of sarcoidosis patients than the general population. This is in keeping with the belief that sarcoidosis represents an abnormal granulomatous response to an environmental exposure in genetically susceptible individuals. Sarcoidosis is rare in people younger than age 18 years. Sarcoidosis is often a benign condition that may run its entire course without detection. It is often discovered in asymptomatic patients on screening chest radiographs.

Sarcoidosis may present as a variety of clinical

syndromes, which vary primarily depending on the distribution of granulomatous

involvement of the affected organs (see Plate 4-155). These include (1) Löfgren

syndrome (erythema nodosum with radiographic evidence of hilar lymph node

enlargement, often with concomitant fever and joint [often ankle] arthritis);

(2) cutaneous plaques and subcutaneous nodules; (3) Heer fordt syndrome (uveoparotid fever);

(4) isolated uveitis; (5) salivary

gland enlargement; (6) central nervous system (CNS) syndromes (usually seventh

nerve palsy); (7)

cardiomyopathy or cardiac arrhythmias; (8) hepatosplenomegaly (with or without

hypersplenism); (9) upper airway involvement (sarcoidosis of the upper

respiratory tract [SURT]); (10) hypercalcemia; (11) renal failure; (12)

peripheral lymphadenopathy; and (13) various forms of pulmonary disease,

including mediastinal adenopathy, interstitial lung disease, endobronchial

involvement with airflow obstruction and wheezing, and pulmonary hypertension.

|

| Plate 4-155 |

Pulmonary hypertension is a potentially

life-threatening complication of sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis associated pulmonary

hypertension is classified in the miscellaneous category (class 5) according to

the World Health Organization classification scheme. This is because there are

multiple mechanisms that may cause pulmonary hypertension in sarcoidosis,

including pulmonary venous hypertension from myocardial involvement, pulmonary

fibrosis causing vascular distortion, hypoxemia from parenchymal sarcoidosis,

compression of the vasculature from the thoracic lymphadenopathy of

sarcoidosis, and direct granulomatous involvement of the pulmonary vasculature.

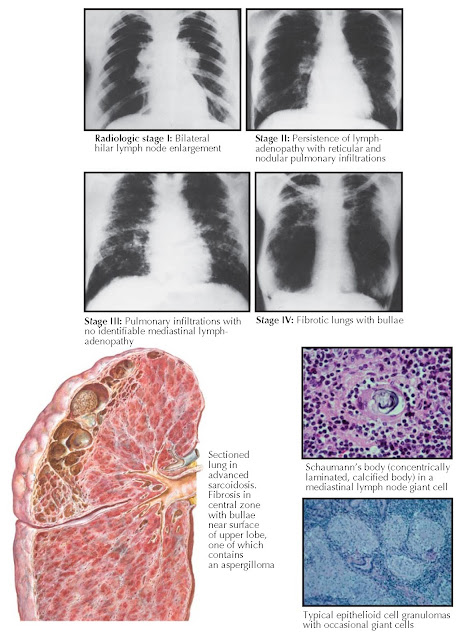

The radiographic presentations of sarcoidosis have

been divided into five stages: (0) a normal chest radiograph, (I) bilateral

hilar and right paratracheal lymph node enlargement, (II) persistence of lymph

nodes with concomitant pulmonary infiltrations, (III) pulmonary infiltrations

with no identifiable mediastinal adenopathy, and (IV) fibrocystic changes that are

usually most prominent in the upper lobes. The fibrosis may be significant, with

retraction of the hilar areas upward and unilateral deviation of the trachea.

Occasionally, aspergillomas may develop in these fibrocystic spaces. Patients

with radiographic stage I sarcoidosis are most often asymptomatic and usually

have normal pulmonary function test results despite the universal presence of

granulomas on lung biopsy specimens at this stage of the disease. With

radiographically discernible pulmonary lesions, a restrictive pattern of

dysfunction may emerge, with loss of lung volumes; decreased pulmonary

compliance; hyperventilation; decreased diffusing capacity; and in the most

severely afflicted patients, hypoxemia. In chronically scarred lungs, evidence

of airway dysfunction usually appears, with decreased FEV1 (forced expiratory volume in

1 second) and diminished flow rates at low lung volumes. Although dyspnea,

pulmonary dysfunction, and prognosis are generally worse with higher

radiographic stages, there is too much overlap for this to be useful to assess

individual patients. It is clear that patients with stage IV radiographs

include nearly all the patients with a very poor prognosis, although not all

patients with stage IV radiographs will fare poorly.

Although chest computed tomography scanning is not

required to assess the status of pulmonary sarcoidosis, it often clearly

identifies mediastinal adenopathy. Furthermore, it may detect parenchymal

disease that is not evident on chest radiographs. Parenchymal sarcoidosis is

commonly located along the bronchovascular bundles and in subpleural locations.

Noncaseating epithelioid granulomas, often accompanied

by giant cells and rarely by small, calcified bodies (Schaumann bodies), are the

fundamental pathologic lesions in sarcoidosis but are nonspecific (see Plate

4-156). However, these granulomas often

cannot be differentiated from the granulomas of fungal infections, berylliosis,

leprosy, brucellosis, hypersensitivity lung diseases, the occasional instances

of tuberculosis when caseation and acid-fast bacilli are not apparent, and

lymph nodes draining neoplastic tumors. Therefore, the diagnosis of sarcoidosis

requires a compatible clinical picture and negative smears and cultures for

organisms causing the diseases. Granulomas frequently develop in several

organs, accounting for the multiple modes of clinical presentation when organ

structure and function are impaired. In the majority of patients with

disability, the organs primarily affected are the lungs, eyes, and myocardium.

The immunopathogenesis of sarcoidosis is not

completely understood. The process probably begins with the interaction of

unknown antigen(s) with antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells

and macrophages. It is postulated that these APCs process these antigens and

present them via human leukocyte antigen class II molecules to T-cell receptors

attached to T lymphocytes, usually of the CD4+ class. After these events occur, T

cells are stimulated to proliferate, and cytokines including interleukin-2 and

interferon-, are produced. These cytokines are thought to enhance pro- duction

of macrophage-derived tumor necrosis factor-(TNF-α). These cytokines and undoubtedly many others are

responsible for granuloma formation.

Elevated levels of serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) have been observed in

active sarcoidosis. However, the serum ACE level is thought not to be specific

or sensitive enough for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. The serum ACE level may

be useful to measure disease activity in cases in which clinical methods of

assessment are difficult or costly.

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis rests on the

demonstration of noncaseating epithelioid granulomas in tissues subjected to

biopsy (skin, lymph nodes, or lung) from a patient with a compatible clinical

picture. As previously mentioned, the clinician must be vigilant that alternate

potential causes of granulomatous inflammation have been reasonably excluded.

|

| Plate 4-156 |

The majority of patients with sarcoidosis can expect a

benign course with complete clearing or nondisabling persistence of

radiographic and other clinical abnormalities. However, a small but significant

number of patients will be disabled, and approximately 4% will die of their

sarcoidosis, usually from respiratory failure. Less commonly, death occurs from

sarcoid cardiomyopathy or CNS involvement. For unknown reasons, cardiac

involvement is the major cause of death from sarcoidosis in Japanese

individuals. Rarely, death may be the result of renal failure or from

hemorrhage because of pulmonary aspergillomas that form in sarcoid bullae.

African Americans tend to have more aggressive forms of sarcoidosis than

whites.

Patients with active sarcoidosis usually respond well

to corticosteroids. The usual course of therapy for acute pulmonary sarcoidosis

is 20 to 40 mg/d prednisone equivalent for 6 to 12 months. Relapse is common

after cessation of prednisone and may require reinstitution of treatment.

Higher doses of corticosteroids

are often required for cardiac involvement, disfiguring facial sarcoidosis (lupus

pernio), and neurosarcoidosis. Prompt treatment with corticosteroids is

indicated for patients with uveitis, CNS disease, hypercalcemia,

cardiomyopathy, hypersplenism, and progressive pulmonary dysfunction, but only

10% of patients with sarcoidosis require mandatory treatment of this kind.

Corticosteroids are not indicated in patients with asymptomatic hilar

lymphadenopathy or minor radiographic pulmonary shadows or for asymptomatic

elevations in serum liver function tests. The arthritis of Löfgren syndrome can usually be managed with nonsteroidal

antiinflammatory agents.

Because prolonged corticosteroid therapy is hazardous,

alternative medications to corticosteroids are often used for chronic

sarcoidosis. In these instances, corticosteroids are often still required, but

the addition of alternative medicines has a corticosteroid-sparing effect such

that the maintenance corticosteroid dose can be reduced. Such medications

include methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, azathioprine,

leflunomide, pentoxifylline, thalidomide, the tetracyclines, and infliximab.