RENAL REVASCULARIZATION

Renal artery stenosis (RAS) is defined as an anatomic narrowing of the main renal artery or its segmental branches, which can lead to secondary renovascular hypertension (RVH) and renal failure if sufficiently advanced. The pathophysiology and diagnosis of this lesion are demonstrated in Plates 4-36 and 4-37. Briefly, the major causes are atherosclerosis, which accounts for about 90% of cases, and fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD), which accounts for most of the remainder. Atherosclerosis, which tends to occur in older individuals with classic risk factors, involves the intimal layer of the artery and develops circumferentially to occlude a progressive fraction of the vessel lumen. FMD, in contrast, causes collagenous dysplasia of either the intimal or medial arterial layers.

Plate 10-17

ENDOVASCULAR THERAPIES FOR RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

INDICATIONS

AND EVALUATIONS

The initial

management of RVH secondary to RAS is with antihypertensive medications,

especially ACE inhibitors. The need for surgical intervention depends on the

patient’s response to antihypertensive medications and the degree (if any) of

renal insufficiency. Renal revascularization may be considered if blood pressure

is refractory to treatment with multiple agents, or if patients have bilateral

stenosis or stenosis of a solitary kidney. In the latter group,

revascularization offers the most benefit if there is no intrinsic renal disease

and renal function is either intact or only mildly impaired. The resistive

index, measured on ultrasound, provides some indication of the degree of renal

parenchymal fibrosis, and it has been shown to predict the degree of benefit

following intervention.

When

revascularization is being considered, preoperative assessment depends on the

cause of the vascular lesion. Patients with FMD are generally young and in

otherwise good health. Patients with atherosclerosis, in contrast, are likely

to have disease elsewhere in the vasculature and are thus at increased risk for

postoperative myocardial infarction and/or cerebrovascular accident. Therefore,

such patients should undergo thorough preoperative evaluation, which may

include cardiac stress testing and/or carotid ultrasound.

PROCEDURE

Endovascular

repair has become the preferred method for renal revascularization. Open surgical repair, in contrast, is typically

reserved for patients who have failed endovascular repair, who have

comorbidities such as aortic or renal artery aneurysms, or who have large and

complex lesions.

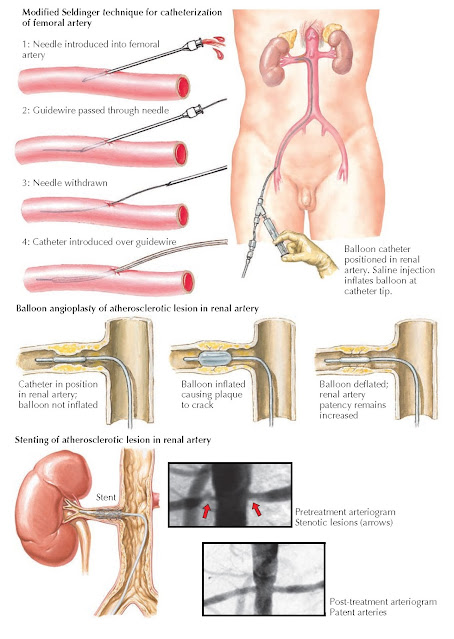

Endovascular

revascularization consists of percutaneous dilation of the renal artery (often

termed percutaneous transluminal angioplasty, or PTA). The femoral or radial

artery is catheterized using the classic or modified Seldinger technique. Under

fluoroscopic guidance, with

occasional injections of contrast material to opacify the vasculature, a

flexible guidewire is advanced across the stenotic segment of the renal artery.

A balloon catheter is then selected that is approximately equal to the diameter

of the nonstenotic portion of the renal artery. The balloon is placed over the

wire to the level of the lesion and then inflated to a high pressure. In

patients with atherosclerosis, the inflated balloon fractures the plaque,

whereas in patients with FMD, the balloon stretches the vessel wall. In either case, perfusion to the kidney is

markedly improved. A postdilation angiogram is performed to assess the results

and determine the presence of any complications, such as injury to the vessel

wall. An adjunct to PTA is the deployment of an endovascular stent, which is an

expandable, metallic mesh sheath that helps maintain vessel patency. Stents are

especially useful in the treatment of atherosclerotic stenoses, which tend to

be rigid and may recoil after balloon dilation.

Surgical

revascularization consists of bypass of the stenotic lesion or, less commonly,

removal of the obstructing plaque (endarterectomy). Aortorenal bypass is often

performed with an autologous graft, such as the saphenous vein. If an

autologous graft is not available, a synthetic polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or

Dacron graft may be used instead. In patients with severe abdominal aortic

disease, in whom aortorenal bypass would be challenging or even dangerous,

alternatives include splenorenal or hepatorenal bypass. If both the abdominal

aorta and celiac artery have severe stenosis, the lower thoracic aorta may

sometimes be used instead. Simultaneous renal revascularization and replacement

of the abdominal aorta should not be attempted unless there is another

indication for aortic replacement, such as a large aneurysm.

Following

either endovascular or surgical treatment, success is defined as elimination of

the stenotic lesion on postprocedure angiogram or a postoperative blood

pressure of less than 140/90. Many patients show improvements in blood pressure

but do not become completely normotensive. The cure rate is greater among

patients with FMD than among patients with atherosclerosis, in part because the

latter group is more likely to have concomitant essential hypertension.

Plate 10-18

SURGICAL THERAPIES FOR RENAL ARTERY STENOSIS

COMPLICATIONS

After

endovascular repair, patients may experience acute tubular necrosis resulting

from the contrast administered during the procedure. To reduce the probability

of this complication, patients should receive adequate hydration both before

and after the procedure. In addition, all other potentially nephrotoxic

medications should be held. Other complications of endovascular repair include

hematoma formation near the puncture site, thrombosis of the renal artery

secondary to balloon trauma or to inadequate anticoagulation following stent

deployment, and restenosis of the repaired lesion. The most serious complication is perforation of the renal

artery, which is typically noted during the procedure. In this case, the

balloon should be reinflated to tamponade the artery. Emergency open repair may

be necessary if bleeding is persistent.

After

surgical revascularization, complications include persistent stenosis, graft

thrombosis, and restenosis of the repaired lesion. Mortality rates are very low

among patients with FMD, owing to their young age and generally good health,

but range from 2% to 6% among patients with atherosclerosis.

Patients who

have recurrent stenosis after endovascular repair often require surgical

revascularization. The surgical approach may be more challenging because of

perivascular inflammation associated with the initial endovascular procedure;

however, this difference does not appear to lower the probability of a

successful outcome. Patients with recurrent stenosis after an initial surgical

revascularization may undergo another surgical procedure with an alternative

bypass route.