RENAL BIOPSY

A renal biopsy yields a small piece of renal parenchyma for histopathologic examination. Because many renal diseases have essentially indistinguishable clinical findings, renal biopsy is often crucial for establishing the correct diagnosis and devising an effective treatment plan. The procedure is generally uncomplicated and, in most cases, can safely be performed by a nephrologist at the bedside.

Plate 10-7

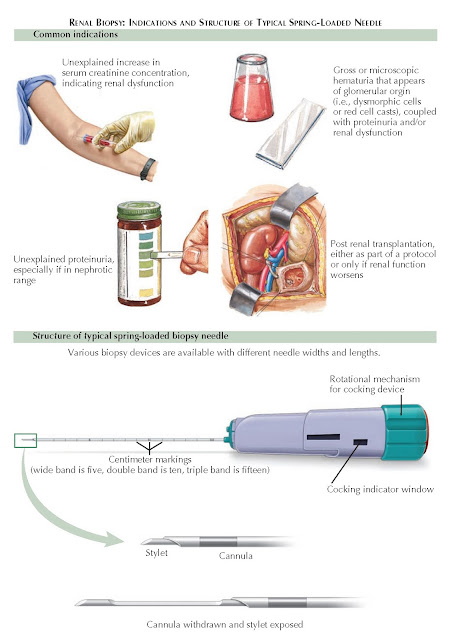

RENAL BIOPSY: INDICATIONS AND STRUCTURE OF TYPICAL SPRING-LOADED NEEDLE

INDICATIONS

The major

indications for renal biopsy include renal failure of unknown cause,

proteinuria, hematuria, and renal transplantation.

Proteinuria.

In

patients with mild proteinuria (1 to 2 g/day) that has no obvious cause, such

as diabetes mellitus, a renal biopsy may be performed to establish a definitive

diagnosis. The exact threshold for biopsy differs across practitioners and

depends on individual clinical judgment. Possible causes of this degree of

proteinuria include glomerulonephritis and mild forms of the diseases that

typically cause nephrotic syndrome, such as focal segmental glomerulosclerosis

(FSGS) or membranous nephropathy (MN). Although tubulointerstitial disease

commonly causes mild proteinuria, a biopsy is generally not required to

establish the diagnosis.

In patients

with nephrotic-range proteinuria (i.e.,3 g/day), a renal biopsy is indicated

to identify the disease process, guide treatment, and determine prognosis.

Possible causes of nephrotic-range proteinuria include primary or secondary

FSGS, MN, minimal change disease (MCD), and (rarely) fibrillary or immunotactoid

glomerulonephritis. If, however, the patient has a diagnosed systemic illness

that is known to cause nephrotic syndrome, a renal biopsy is typically not

required. Examples include patients with long-standing diabetes mellitus and

concurrent diabetic retinopathy, or patients with amyloidosis seen on a biopsy

of another affected organ system. In addition, young children with nephrotic

syndrome are generally presumed to have MCD, with a renal biopsy only performed

if empiric treatment for this condition fails.

Hematuria.

In

patients with gross or microscopic hematuria, the initial workup should focus

on urologic abnormalities, such as nephrolithiasis, neoplasm, or infection. The

presence of dysmorphic red cells, proteinuria, and renal insufficiency, however,

strongly points toward glomerular disease. Many renal diseases are associated

with microscopic hematuria, including essential hematuria, acute interstitial

nephritis, IgA nephropathy, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis,

postinfectious glomerulonephritis, lupus nephritis, cryoglobulinemia,

fibrillary/immunotactoid glomerulonephritis, ANCA-associated vasculitis,

malignant hypertension, atheroembolic renal disease, renal infarction,

thrombotic microangiopathy, Henoch-Schönlein purpura, thin basement membrane

nephropathy, hereditary nephritis, and anti-GBM disease. A kidney biopsy is

essential for establishing the correct diagnosis and determining an optimal

treatment plan.

Occasionally,

patients may have isolated hematuria (i.e., without proteinuria or renal

insufficiency). The differential diagnosis for such patients includes thin basement membrane

disease, mild IgA nephropathy, and hereditary nephritis. A kidney biopsy is

typically not performed, however, because treatment is not instituted unless

there is significant proteinuria or renal insufficiency.

Renal

transplant. Patients who have undergone renal transplant and subsequently develop

renal failure should have a biopsy if their renal function does not improve

after provision of intravenous fluids. In such circumstances, a biopsy is

helpful for differentiating between various entities, such as acute or chronic

rejection, drug toxicity (especially from calcineurin

inhibitors), and BK virus infection. Some centers also routinely take biopsies

from transplanted kidneys at predetermined time points, even in the absence of

overt dysfunction because some renal disease may initially be clinically

silent.

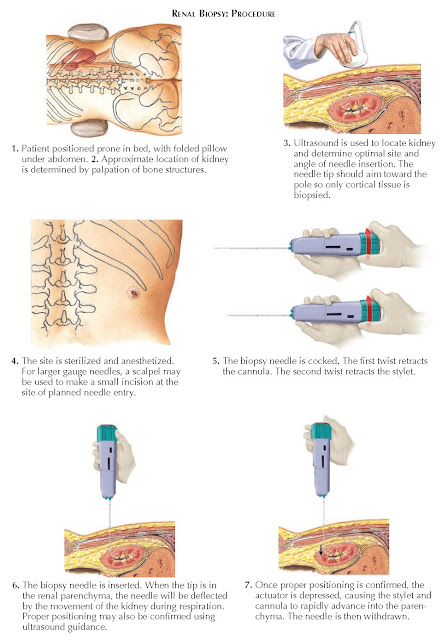

PROCEDURE

Before a

patient undergoes a renal biopsy, anticoagulation medications should be

stopped, and bleeding risk should be evaluated by obtaining a prothrombin time,

partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count. Any bleeding diathesis should

be corrected, if possible, before the procedure.

Most

patients can undergo a percutaneous biopsy, which is performed at the bedside;

however, select patients may require alternate approaches, including open,

laparoscopic, and transjugular biopsies. The major indications for these

techniques include an uncorrectable bleeding diathesis, morbid obesity,

solitary kidney, infection of the skin over the kidneys, and failed

percutaneous attempts.

For a

percutaneous biopsy, most patients should be placed prone, with a folded pillow

under the abdomen. An ultrasound is performed to visualize the kidney and

determine the location and angle of needle insertion. The upper or lower pole

should be targeted so that only cortical tissue is acquired. Hydronephrosis,

multiple cysts, or small hyperechoic kidneys may be seen, which increase the

bleeding risk and should be considered relative contraindications.

Once the

initial ultrasound is complete, the site is dressed and draped in normal

sterile fashion. The site is injected with a local anesthetic, and a scalpel

may be used to nick the skin at the area of planned needle insertion. The

biopsy needle, which consists of a spring- loaded outer cannula and inner

stylet, is then cocked as shown in the diagram. The needle is passed through

the skin into the renal parenchyma, often using ultrasound for real-time

guidance. The patient is instructed to hold his or her breath, and then the

actuator button is depressed, causing rapid advancement of both the inner

stylet and outer cannula to the device’s predetermined penetration depth. A

tissue core is acquired as the cannula rapidly passes over the stylet. Two or

three cores should be acquired to ensure an adequate sample. The adequacy of

the tissue cores can be assessed using low-power microscopic examination. An

adequate sample should contain a minimum of 8 to 10 glomeruli. The cores should

be transported in normal saline to the pathology laboratory or placed in

fixatives if the laboratory is not on site. A renal pathologist then examines

the tissue using light microscopy, electron microscopy, and immunofluorescence

or immunohistochemistry. Typical

routine stains for light microscopy include hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid–Schiff, Jones’ silver methenamine, and

trichrome.

COMPLICATIONS

The main

complications of a renal biopsy include bleeding, pain, damage/puncture of

surrounding structures (liver, spleen, bowel), and arteriovenous fistula

formation. Bleeding is by far the most common complication, and it can occur

into the urine collecting system,

perinephric space, or subcapsular space. Patients should thus be monitored for

approximately 4 to 6 hours after the procedure, with vital signs, hemoglobin

levels, and urine color noted. Some centers perform a follow-up computed

tomography (CT) scan or ultra-sound a few hours after the biopsy. In the event

of a major bleed, transfusions or therapeutic procedures (e.g.,

angioembolization or laparotomy) should be performed as needed. In very rare

cases, a renal biopsy results

in kidney loss or death.