HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS

Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) and type 2 (HSV2) are the two viruses that are responsible for the production of both mucocutaneous and systemic disease. Mucocutaneous disease is overwhelmingly more common than systemic disease such as HSV encephalitis. HSV infections are ubiquitous in humans, and almost all adults develop antibodies against one of these viruses. Most infections are subclinical or so mild that they are never recognized by the patient. HSV infections are predominantly oral or genital. The virus becomes latent in local nerves and can be reactivated to produce future outbreaks. Currently, there are eight known herpesviruses that infect humans, including HSV1 and HSV2. HSV infections can cause severe, life-threatening central nervous system (CNS) disease in immunocompromised patients and in neonates. Many unique cutaneous forms of HSV have been described with their own clinical characteristics.

Clinical

Findings: HSV can be spread from infected to uninfected individuals by close

contact (e.g., kissing, sexual contact). The virus is shed from the infected

host both when active lesions are present and when no clinical evidence of

disease can be seen. It is believed that sub- clinical shedding of the virus is

responsible for a great deal of transmission. HSV can cause oral labial disease

(gingivostomatitis or herpes labialis) or genital disease, the main

mucocutaneous forms of the disease. Most cases of oral labial disease are

caused by HSV1, and genital disease is caused predominantly by HSV2. This is

not always the case, and one can no longer assume the viral type from the

clinical location of disease. HSV infections in other areas are becoming more

common, and recurrent bouts of disease on the buttocks is one of the most

frequently seen presentations.

|

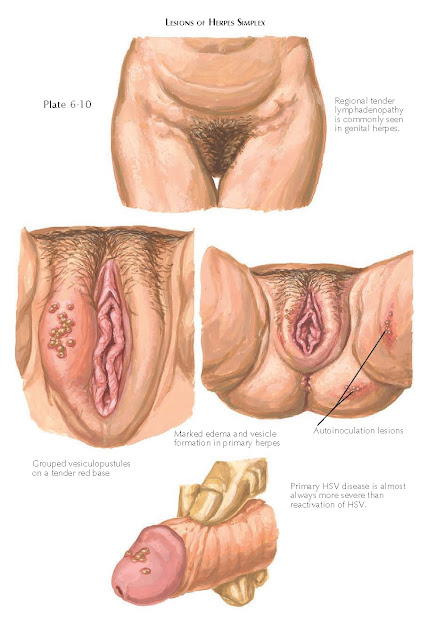

| LESIONS OF HERPES SIMPLEX |

The initial

HSV infection can be subclinical, mild, or severe. Subsequent reactivation of

the virus typically never approaches the severity seen in the initial primary

infection. The exception occurs with immunosuppressed patients, in whom a widespread

or chronic localized version of the infection may occur. Primary infection

manifests with severe, painful mucocutaneous blistering and erosions. Primary

oral labial herpes can lead to weight loss, fever, gingivitis, and pain. This

is most commonly seen in children and is associated with tender cervical

adenopathy. The infection spontaneously resolves within 2 to 3 weeks. If

treated, the disease may be slightly decreased in length and severity, but this

is highly dependent on the timing of diagnosis and initiation of therapy.

Herpes

labialis is

the term given to recurrent episodes of oral labial herpes. The episodes are

milder than the primary infection and often start with a prodrome. Most

patients complain of a tingling or painful sensation hours to a day before the

appearance of herpes labialis. Patients can use this knowledge to their

advantage and begin antiviral therapy at the first indication of recurrence to

decrease the severity of the episode or abort it all together. Herpes labialis,

also known as a cold sore, appears as a vesicle or bulla that quickly breaks

down and forms an erosion and crusted papule or plaque. The lesions last for a

few days to 1

week and can cause significant

psychological issues.

Herpes

infection of the genital region is spread by sexual contact and is one of the

most common of all sexually transmitted diseases. Initial episodes of genital

herpes infection manifest with fever, adenopathy, and painful ulcerations and

blistering of the affected region. The primary episode is always more severe

than subsequent reactivations of the virus. The ulcerations are grouped vesciulopustules

on an erythematous base. They are extremely tender and easily rupture to form

shallow ulcerations that appear “punched out” with an overlying serous crust.

The cervix is often involved, and scarring can occur. Genital herpes infection

almost universall causes dysuria and inguinal adenopathy that is tender.

Recurrent

episodes of genital herpes produce a milder version of the primary infection.

The systemic constitutional symptoms are often absent, but the grouped vesicles

and ulcers can cause excruciating pain and social stigma. The frequency and

severity of recur- rent episodes in an individual patient are variable and

impossible to predict. A generalization can be made that those who have more

severe primary infections tend to have more relentless recurrences.

Herpetic

whitlow is

the name given to a specific form of infection that is most commonly seen in

medical laboratory workers and health care providers. It occurs from accidental

inoculation of the herpesvirus into the skin. The finger is the area most

commonly involved, because of accidental needle sticks. A painful primary viral

infection may occur at the site of inoculation.

Eczema

herpeticum, Kaposi’s varicelliform eruption, is often encountered in a young

child with severe atopic dermatitis who is exposed to the herpesvirus. Because

of the widespread skin disease, the virus is able to infect a large surface

area of the body. This results in extensive skin involvement with multiple

vesicles and punched-out ulcerations.

The

transmission of HSV from mother to child during the birthing process is of

significant concern, and mothers with active HSV disease at the time of

delivery most likely should undergo cesarean section to help decrease the risk

of transmission. Neonatal HSV infection is a life-threatening disease. The

neonate may have widespread multiorgan disease, with CNS involvement being the

major cause of morbidity and mortality. Temporal lobe involvement can lead to

seizures, encephalitis, and death. The skin is always infected, and this is a

clue for the clinician to search for other organ system involvement, especially

involvement of the CNS and the eye. Ocular infection can lead to severe corneal

scarring and blindness.

|

| LESIONS OF HERPES SIMPLEX |

HSV

encephalitis is a life-threatening disease that causes a necrotizing

encephalitis. Patients complain of an acute onset of fever and headache, with

rapidly evolving seizures and focal neurological deficits. Without treatment,

coma and death occur in three quarters of affected patients. The temporal lobes

and insula are almost always affected. Prompt recognition and therapy have

decreased the mortality rate to 1 in 4. A Tzanck preparation is a long-used

bedside procedure that takes only a few minutes to perform and is positive in

cases of HSV1, HSV2, or varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection. The procedure

does not differentiate among the three viruses. However, HSV infection can be

distinguished from varicella clinically. The procedure is done by unroofing a

vesicle and scraping its base with a no. 15 blade scalpel. The scrapings are

placed on a glass slide and allowed to air dry for 1 to 2 minutes. A blue stain

such as Giemsa or toluidine blue is applied for 60 seconds and then gently

rinsed off. The slide is dried, mineral oil is applied, and the preparation is

covered with a microscope cover slip. It is then ready to be viewed.

Multinucleated giant cells are readily seen throughout the sample, confirming

the viral etiology of the

blister.

Rapid

immunostaining is available and can be used with high sensitivity and

specificity to diagnose and differentiate the various herpesvirus types. This

form of direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) testing is similar to the Tzanck

preparation. As in the Tzanck preparation, scrapings of the blister base are

placed on a glass microscope slide. The slide is stained with antibodies

corresponding to the various herpesviruses. The sample is viewed under

fluorescent microscopy, and a positive sample fluoresces with one of the specific viral stains. This test takes

1 to 2 hours to perform.

Viral tissue

cultures can also be performed to differentiate the HSV types, but the results

can take days to 1 week to obtain. This is the most sensitive and specific test

for the infection.

Histology:

Examination

of a biopsy specimen of a blister shows ballooning degeneration of the

epidermal keratinocytes. This degeneration forms the blister cavity. There is a mixed

inflammatory infiltrate around the superficial and deep dermal vascular plexus.

Multi- nucleated giant cells are found at the base of the blister pocket. The

skin biopsy findings are unable to differentiate HSV1 from HSV2 or from VZV

infection.

Pathogenesis:

HSV1

and HSV2 are double-stranded DNA viruses encased within a lipid envelope. Along

with VZV, they are classified in the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae. The five

other human herpesviruses are classified slightly differently. The virus

attaches to the host cells via specialized glycoproteins expressed on its lipid

envelope. The lipid envelope then fuses with the host cell, allowing the virus

to gain entry into the cytoplasm. Many glycoproteins are responsible for this

attachment and fixation and the entrance into the host cell. The HSV capsid,

which is an icosahedron-shaped structure, migrates from the cytoplasm to the

nucleus of the cell. The viral capsid attaches to the nuclear membrane through

the interaction of various membrane proteins and is capable of transferring its

DNA into the cell nucleus.

Once the HSV

DNA has gained entrance into the nucleus, it can become latent and quiescent or

can actively replicate new virus particles. When they are actively replicating,

the HSV particles often have a cytotoxic effect on the affected cell after

viral replication has occurred; this ensures the production of viral progeny

and their release from the host cell. HSV is capable of hijacking the host

cell’s replication protein apparatus. HSV uses the host cell DNA polymerase to

replicate its DNA and uses the cellular machinery to produce proteins required

for viral replication. The virus carries various DNA genes that can be

expressed early during the course of infection or later when the virus is ready

to produce progeny. The early gene products are important for replication and

regulation of the viral DNA genes. The late gene products encode the viral

capsid. Once the viral elements have been produced in sufficient quantity and

in the proper ratio, the viral particles spontaneously converge to produce a

capsid, which encapsulates the viral DNA. This occurs within the host cell

nucleus. The virus then passes through the nuclear membrane and the cytoplasmic

membrane, acquiring its lipid bilayer. At this point, the virus is free to infect

another host.

Alternatively,

after it enters the cell’s nucleus, the virus may become latent. This is

particularly the case in neural tissue. The viral DNA inserts itself into the

host DNA, where it lies dormant and hidden from expression until reactivation

occurs at some later time. It accomplishes this by specialized folding of the

DNA and histone complex so as not to allow for viral gene expression. When the

virus is reactivated and ready to produce viral particles, this mechanism of

latency is somehow deactivated, allowing for viral reproduction.

|

| HERPES SIMPLEX VIRUS ENCEPHALITIS |

Treatment:

Therapy

and its efficacy are highly dependent on the timing of administration.

Antiviral medications work by inhibiting viral synthesis, and they work best

when used early in the course of disease. Primary infections should all be

treated with one of the antiviral agents in the acyclovir family. These closely related medications

include acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir, and topical penciclovir.

Recurrent episodes of the disease can be treated at the time of outbreak or

with a chronic daily suppressive regimen. Widespread eczema herpeticum, CNS

infection, or infection in an immunosuppressed patient is probably best treated

with intravenous antiviral medication. The acyclovir family of medications are

converted to their active form by viral-specific thymidine kinase. After

conversion, this metabolite

is a potent inhibitor of viral DNA polymerization. These medications are highly

specific for the viral enzymes and have an excellent side effect profile.

Acyclovir-resistant HSV has become well recognized and is best treated with

foscarnet. Foscarnet does not require modulation by thymidine kinase to become

an active inhibitor of HSV replication, thereby bypassing the HSV resistance

mechanism. No medication to date has shown activity

against latent viral infection.