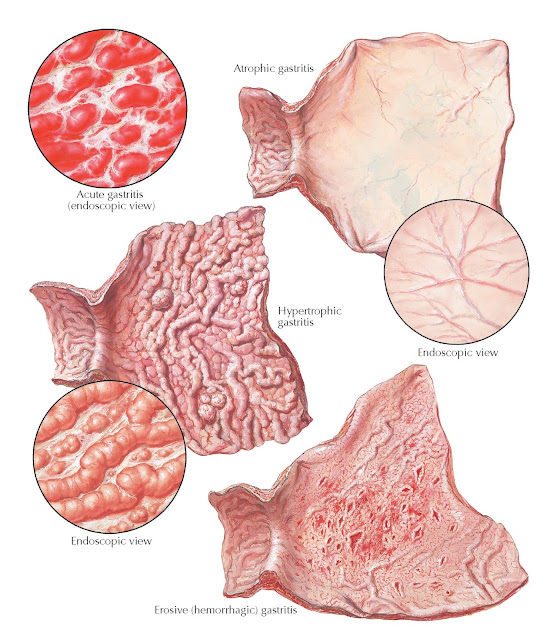

GASTRITIS

Gastritis is an inflammation of the mucosal lining of the stomach. It can occur suddenly (acute) or gradually (chronic). Gastritis can be caused by irritation or inflammation from excessive alcohol use or the use of certain medications such as aspirin or other anti inflammatory drugs. It may also be caused by H. pylori and other bacterial and viral infections, pernicious anemia, and bile reflux.

Gastric irritation from abuse of

alcohol, coffee, and tobacco and from chemicals and drugs such as NSAIDs and,

perhaps, corticosteroids is the main cause of acute gastritis. Acute

gastritis may also develop during many febrile infections, such as typhoid,

pneumonia, and diphtheria. H. pylori infection can present with acute

gastritis. The gastric mucosa in acute gastritis is erythematous, often with

erosions, and may be covered with a thick mucus. Symptoms of gastritis vary

among individuals, and in many people there are no symptoms. The most common

symptoms include epigastric pain or discomfort, nausea or indigestion,

vomiting, a burning or gnawing feeling in the stomach between meals or at

night, and a disagreeable taste. A corrosive type of gastritis, originating

from the intake of strong chemicals such as lye, can lead to a localized or diffuse

necrosis and permanent scarring.

|

| Plate 4-42 |

Erosive hemorrhagic gastritis is characterized by multiple, diffuse erosions

in an inflamed mucosa. Nausea, anorexia, pain, and gastric hemorrhage may

occur. This acquires a special clinical significance with its tendency to cause

severe, at times life-endangering, hemorrhages. Larger arteries extend quite

frequently as far up as the epithelium and may become involved in some of the

many small, but by no means superficial, erosions. Whenever the origin of

gastrointestinal bleeding cannot be identified, the possibility of an erosive

hemorrhagic gastritis must be seriously considered, especially in severely ill

hospitalized patients. Endoscopy is important for the diagnosis, though during

an episode of acute bleeding the mucosa may not be well visualized. At

laparotomy the diagnosis may still be difficult, because, even when viewing the

mucosa directly after gastrostomy, the small erosions (i.e., the source of the

bleeding) may not be well seen macroscopically.

A similar type of hemorrhagic

gastritis has been observed after partial resection of the stomach

or after gastroenterostomy or ulcer. This should be kept in mind if the

suspicion of a bleeding peptic “anastomotic ulcer” cannot be confirmed

unequivocally by x-ray studies, endoscopically, or at laparotomy. Under such

circumstances, vagotomy may be the best procedure to stop the bleeding. It has

helped in many cases and, in any event, is preferable to an additional

resection.

Chronic atrophic gastritis is a process of chronic inflammation of the

stomach mucosa, leading to loss of gastric glandular cells and their eventual

replacement by intestinal and fibrous tissues. This may be an aftermath of an

acute gastritis, but many other possible etiologic factors of exogenous or

endogenous origin need to be considered. Chronic atrophic gastritis has a close

relationship to pernicious anemia and vitamin B12 deficiency. The relationship

of chronic atrophic gastritis and, more specifically, pernicious anemia with

malignancies has not been clarified. The characteristic features of chronic

atrophic gastritis endoscopically are the disappearance of the folds and the

thinness of the mucosa through which shines the vascular net, both arterial and

venous. Microscopically, the chief and parietal cells are considerably reduced

in size and number; the epithelial cells are transformed to a great extent into

goblet cells, or undergo metaplastic changes. The clinical manifestations are

rather nonspecific. Upper endoscopy with biopsies of the gastric body is used

to establish the diagnosis.

With chronic hypertrophic

gastritis the situation is clinically much the same, except that

hyperacidity is present in most cases, and the distribution of the rugae and

the “cobblestone” appearance of the mucosal surface, seen roentgenographically,

provide more often the right clue for diagnosis; endoscopy is needed to make

the unequivocal diagnosis. The rugae are strikingly thickened and, even at

autopsy, do not flatten out when the wall is stretched. Ménétrier disease (also

known as hypoproteinemic hypertrophic gastropathy) is a rare, acquired disorder

of the stomach characterized by greatly thickened gastric folds and excessive

mucus production, with resultant protein loss leading to diarrhea. Other

conditions, such as lymphoma and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, can cause

hypertrophic mucosal folds in the stomach, and use of proton pump inhibitors

can also be a cause. In Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, or gastrinoma, the elevated

serum gastrin levels lead to parietal cell hypertrophy, prominently in the

fundus and body of the stomach. The use of proton pump inhibitors results in

gastric hypoacidity leading to increases in gastrin levels and, also, parietal

cell hypertrophy.