CENTRAL DIABETES

INSIPIDUS

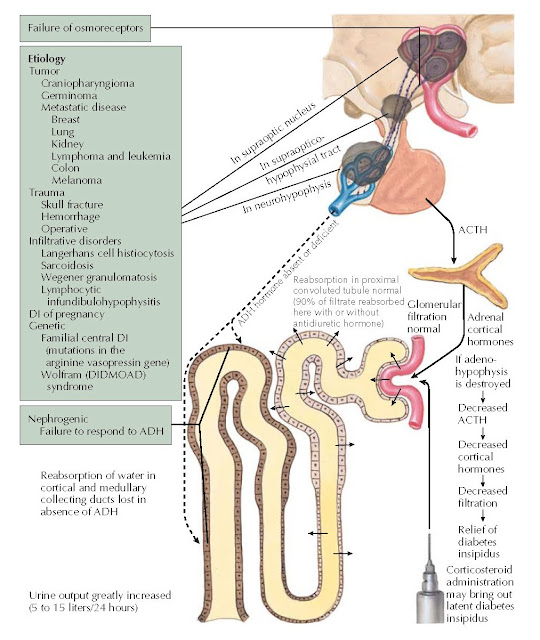

Diabetes insipidus (DI) literally means a large volume of urine (diabetes) that is tasteless (insipid). Central DI is characterized by a decreased release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH; vasopressin), resulting in polydipsia and polyuria. ADH deficiency may be a result of disorders or masses that affect the hypothalamic osmoreceptors, the supraoptic or paraventricular nuclei, or the superior portion of the supraopticohypophyseal tract. Approximately 90% of the vasopressinergic neurons must be destroyed to cause symptomatic DI. Because the posterior pituitary gland stores but does not produce ADH, damage by intrasellar pituitary tumors usually does not cause DI. The most common causes of central DI are trauma (e.g., neurosurgery, closed-head trauma), primary or metastatic tumors, and infiltrative disorders. Central DI can be exacerbated by or first become apparent during pregnancy, during which ADH catabolism is increased by placental hyperproduction of the enzyme cysteine aminopeptidase (vasopressinase).

Persons with central DI typically

have a sudden onset of polyuria and thirst for cold liquids. They usually wake

multiple times through the night because of the need to urinate and drink fluids often ice cold water

from the refrigerator. When seen in the outpatient clinic, these patients

usually have a large thermos of ice water by their side. The degree of polyuria

is dictated by the degree of ADH deficiency urine output

may range from 3 L/day in mild partial DI to more than 10 to 15 L/day in severe

DI. In patients with concurrent anterior pituitary failure, secondary adrenal

insufficiency is associated with decreased glomerular filtration (associated with

decreased blood pressure, cardiac output, and renal blood flow), leading to

decreased urine output. Glucocorticoid deficiency also increases ADH release in patients

with partial DI. These effects are reversed when glucocorticoid replacement is

administered and DI is “unmasked,” resulting in the rapid onset of polyuria.

|

| Plate 1-27 |

Neurosurgery in the sellar region

(either by craniotomy or transsphenoidal routes) or blunt head trauma that

affects the hypothalamus and posterior pituitary may result in DI. As many as

50% of patients experience transient central DI within 24 hours of pituitary

surgery; it resolves over several days. With the minimally invasive endoscopic

transnasal transsphenoidal approach to pituitary surgery, the rate of

postoperative permanent DI is less than 5%; however, with transcranial

operations and with larger tumors that have hypothalamic involvement (e.g.,

craniopharyngioma), up to 30% of patients develop permanent DI. Damage to the

hypothalamus by neurosurgery or trauma often results in a triphasic response:

(1) an initial polyuric phase related to

decreased ADH release because of axon shock

and lack of action potential propagation beginning

within 24 hours of surgery and lasting approximately 5 days; (2) an

antidiuretic phase (days 6–12), during which stored ADH is slowly released from

the degenerating posterior pituitary, and hyponatremia may develop if excess

fluids are administered; and (3) a permanent DI after the posterior pituitary

ADH stores are depleted. In 10% to 25% of all patients who undergo pituitary

surgery, only the second of these three phases is seen, and DI never develops

because surgical trauma only damages some of the axons; this results in

inappropriate ADH release, but the intact axons continue to function and

prevent the onset of DI. However, this transient, inappropriate release of ADH

can have serious consequences, with marked hyponatremia that peaks

approximately 7 days after surgery and that may be associated with head-aches,

nausea, emesis, and seizures. This sequence of events can be avoided by

advising the patient to “drink for thirst only for the first 2 weeks” after a

pituitary operation.

Primary (e.g., craniopharyngioma,

germinoma) or metastatic (e.g., breast, lung, kidney, lymphoma, leukemia,

colon, or melanoma) disease in the brain can involve the hypothalamic–pituitary

region and lead to central DI. Polyuria and polydipsia may be the presenting

symptoms of metastatic disease.

Patients with Langerhans cell

histiocytosis are at high risk of developing central DI because of

hypothalamic–pituitary infiltration. Additional infiltrative disorders that may

cause central DI include sarcoidosis, Wegener granulomatosis, and autoimmune

lymphocytic infundibulohypophysitis.

Familial central DI is an autosomal

dominant disorder caused by mutations in the arginine vasopressin gene, AVP.

The incorrectly folded and mutant AVP prohormone accumulates in the endoplasmic

reticulum of the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei and results in cell

death. Thus, children with autosomal dominant disease progressively develop AVP

deficiency, and symptoms usually do not appear until several months or years

after birth. Indeed, the posterior pituitary bright spot on magnetic resonance imaging (see Plate 1-8) is

present early and then slowly disappears with age and advancing damage to the

vasopressinergic neurons.

Wolfram (DIDMOAD [diabetes

insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness]) syndrome is

characterized by central DI, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, and deafness.

Diabetes mellitus typically occurs before central DI. This syndrome is usually

inherited in an autosomal recessive manner with incomplete penetrance, although

evidence suggests that there is another form of the disorder that may be caused

by mutations in mitochondrial DNA.