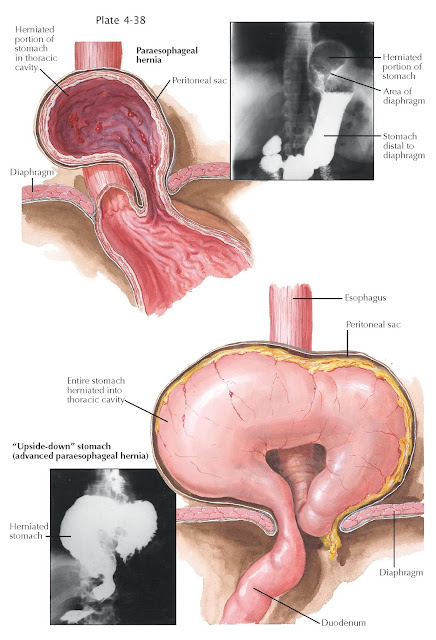

PARAESOPHAGEAL HERNIA AND GASTRIC VOLVULUS

A paracardial or paraesophageal hernia is seen less frequently than is a sliding diaphragmatic hernia and is characterized by the protrusion of the gastric fundus into the intrathoracic space alongside the esophagus, which is of normal length and in the usual and fixed position. The cardia and its attachment by the gastrophrenic ligament remains intact while the fundus slips through a fibromuscular defect directly to the left or right of the gastroesophageal junction. The parietal peritoneum, which normally covers the abdominal surface of the diaphragm, has prolapses and serves as the outer wall of the hernia sac. These anatomic relations explain why, with a paraesophageal hernia, there is no insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter mechanism and, hence, no occurrence of peptic esophagitis.

The hiatus

between the terminal portion of the esophagus and the diaphragmatic crus (or

phreno- esophageal ligament) is, as a rule, so narrow that it may interfere

with the circulation of the prolapsed portion of the fundus, which will

consequently become congested. The venous congestion leads to inflammatory

reactions of the mucosa, which tends then to erode or bleed, particularly in

the area of the hiatal defect. The resulting blood loss, in some cases, may be

of such magnitude as to produce a chronic and recurrent anemia, which may be

the first and only clinical sign of the disease. The paraesophageal hernia,

however, assumes its clinical significance essentially by the potential danger

of strangulation of the herniated parts. The predominant symptoms with this

type of hernia are epigastric and substernal pain, nausea, and, rarely,

dysphagia. An increase in the intermittent attacks of pain, the appearance of

hematemesis, and a tendency toward cardiovascular collapse should always arouse

the suspicion of a possible strangulation. Careful examination of a chest

radiograph may reveal a gas bubble from the herniated gastric fundus adjacent to the normally

placed esophagus with normal topographic relations of the gastroesophageal

junction.

An extreme

variant of the paraesophageal hernia has been quite pertinently called the upside-down

stomach. In such instances a markedly widened hiatus in the diaphragm has

permitted the entire stomach to enter the thorax and lie within the herniated

sac. The stomach is rotated around its longitudinal axis, and the more movable major curvature

thus becomes the dome of the prolapse. The cardia and pylorus are in close

apposition to each other, and lie, with such a complete herniation of the

organ, at the same level.

Once the

diagnosis of a paraesophageal hernia has been established, its surgical repair

is definitely indicated, not only because of the symptoms and signs (epigastric

pain and anemia) but more so because of the always imminent danger of incarceration.